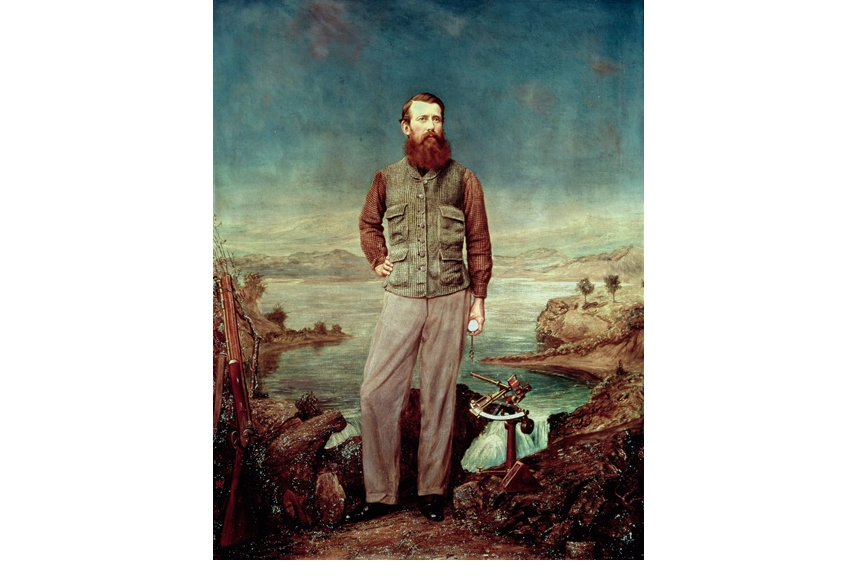

Every day in Kensington Gardens I jog round the bleak granite obelisk inscribed IN MEMORY OF SPEKE. VICTORIA NYANZA AND THE NILE 1864, which my family calls ‘Speke’s Spike’.

That river is known to me a bit: I have stood on the glaciers of Ruwenzori at 16,000 feet, which feed it via Lake Albert. I was the first (with two others) to descend for 100 miles the water of the Blue Nile from its Ethiopian source. I have waded the Sudd with Anuak guerrillas.

Tim Jeal’s gripping book pulls the whole astonishing story together. Many a red-blooded Spectator reader will relish it, and buy it, since it’s as intricate and unexpected as the source of the river itself.

All main players were British, all exemplars of grit, resourcefulness and courage on a heroic scale, each emerging in vibrant contrast: the obsessive doyen and medical missionary from Lanarkshire; the brilliant linguist and traveller-spectacular; the gentleman adventurer lured by the unknown; the Welsh foundling, reared in a workhouse, starting out as a newspaperman; and the lofty grandee who’d bought his orphaned lover and companion in a Turkish auction. To wit: David Livingstone, Richard Burton, John (Jack) Speke, Henry Moreton Stanley and Samuel Baker. They sought a common prize, and shared a common rivalry.

For to be the first to reveal that source to the world of Queen Victoria would be the equivalent today of being the first to set foot on Mars. From Herodotus onwards many had failed. The unerring contribution of Ethiopia’s Blue Nile — joining the White just south of Khartoum — to the annual flooding of lower Egypt was beginning to be suspected. But the great mystery of the provenance of the White lay locked up in unknown equatorial Africa.

Livingstone was there first, in the Zambezi basin and reaching Lake Nyasa. Then Burton (‘driven by the devil’, he would say) half-mythic penetrator of forbidden Mecca in disguise, accepted the challenge of the Royal Geographical Society to crack the Nile. He took with him young Speke, with whom he had nearly died in Somaliland. By February 1858 the pair had reached Ujiji, the Arab slaving entrepot on the unknown, 420-mile-long Lake Tanganyika. They learned of a river at the far north end. Might it run out? After 19 days’ paddling in two vast dugouts Burton was told this Rusizi flowed in. His hopes were ‘dashed to the ground’, he confessed. Albeit with a mere six hours’ more paddling to confirm it, he turned the party back. He preferred doubt.

Halfway back to the coast at Zanzibar Burton fell sick, and Speke went for a walk-about northwards. He found a great new sheet of fresh water, he was to name Victoria, its altitude markedly higher than Tanganyika’s. Returning to camp he let slip to Burton after breakfast he had found the Nile’s source. ‘Foolish speculation’, derided Burton. The seed was sown of unrelenting antagonism.

Speke was soon back exploring his lake. From the ritually murderous court of the Kabaka of Buganda, whose territory straddled the northern littoral, he was soon to gaze upon the outlet of a serious river spilling over 16-foot falls. It was 26 July 1862. To follow it all the way down its known course proved impossible. Meanwhile, Sam Baker was proceeding up the river, on whose banks at Juba the two explorers met. Baker had no choice but to switch his destination south-westwards, to a third great undiscovered lake, Luta Nzike, which Speke surmised received the water of ‘his’ Nile, only to release it immediately into its continuing northward flow.

This Luta Nzike (‘death to locusts’in garbled vernacular) was soon to be Lake Albert. Earlier rumour of its existence implanted the speculation for both Livingstone and Burton separately that Tanganyika (or other lakes) flowed by some uncharted western course by way of it into the true Nile, by-passing Victoria. By now Burton had changed his story. Tanganyika’s north river flowed out of it.

On such claims, speculative or mendacious, he and Livingstone (who loathed each other) were invited to confront Speke at a gathering of the British Society for the Advancement of Science, under the august Roderick Murchison, President of the Royal Geographical Society on 27 September 1864. (Baker was not to return and report — endorsing Speke’s guess — until 1865).

The nation was agog. But the afternoon before, Speke was out with his cousin rough-shooting, and crossing a stone wall snagged his unguarded trigger with a twig. He died within 15 minutes. In wordy mourning, Burton hinted at suicide. Murchison provided the wary inscription for Speke’s spike, and assigned the proven resolution to Livingstone.

But to trump both Speke and Burton, Livingstone back in Africa needed to prove the northward flowing Lualaba fed Luta Nzike, by-passing Victoria. In that hopeless attempt he perished (1873), praying in the name of Jesus ‘for it to be granted to him to finish the task’, that task no longer being the abolition of the Arab slave trade or converting Africans to Christ, but for himself to be — as it were — the first on Mars.

It took Stanley to confirm (1871) the Rusizi flowed into Tanganyika, which drained via the Lukuga into the Lualaba (1875),which became not the Nile but the River Congo. Burton was still ‘in heartfelt sorrow’ that Speke had not been spared to see his deductions from his ‘wonderful discovery [of 1862] proved correct’. Ah, the condescension of a tearful crocodile! Speke had been right all along.

How intimately Jeal knows them all, and brings them back to life for us. As a person, Jack Speke, whose true prize it was, is nearest to the rest of us, with a double-plus for hunch.

Comments