‘Frankie and Johnny were sweethearts; Lordie, how they could love.’ The ballad has many variant versions but the denouement is always the same; he was her man and he did her wrong. Rooty-toot-toot three times she shoot, and Johnny ended up in a coffin.

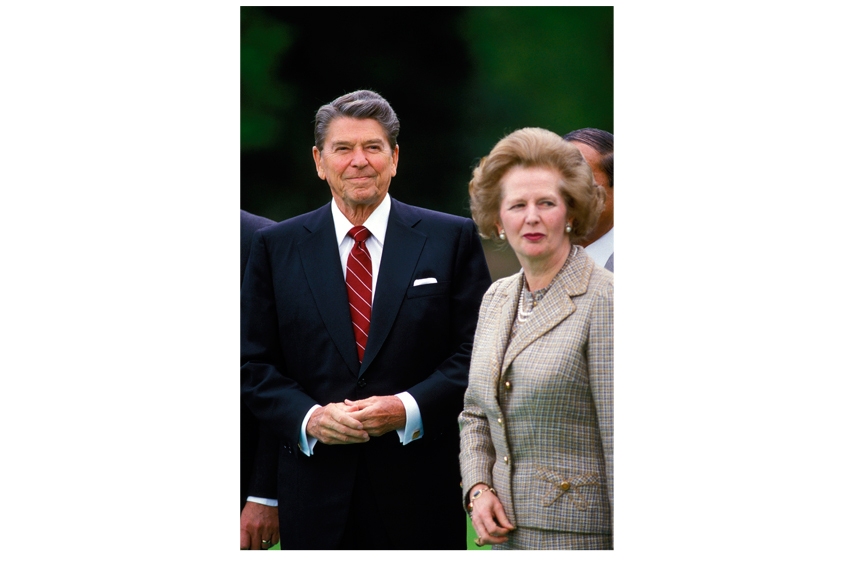

Thatcher and Reagan were sweethearts; Lordie, how they could love. But Reagan did her wrong: over Grenada, over nuclear disarmament, as near as nothing over the Falklands. The relationship was to end in ostentatious affection, but if Mrs Thatcher had had a gun in that celebrated handbag, it might have been a case of rooty-toot-toot all over again.

Richard Aldous claims, or, at least, lets the blurb make him claim, that ‘the weakest link in the Atlantic Alliance of the 1980s was the association between its two principal actors.’ His intelligent, authoritative and extremely readable book does not bear this out. What it shows is that, whether you are talking about Churchill and Roosevelt, Adenauer and De Gaulle, Thatcher and Reagan or any other pair of international statesmen, what counts in the end is not personal liking or ideological rapport but the national interest. If Reagan felt that the interests of the United States required a certain course of action, then that course would be taken: it might be dressed up slightly to accommodate the needs of a friend but essentially it would be unchanged.

This became painfully clear to Thatcher when the Americans invaded Grenada in 1983. A left-wing coup in the tiny Caribbean island seemed to threaten the establishment of another Cuba on the United States’ doorstep. Grenada was an independent country and a member of the Commonwealth. Britain was disturbed by this development but did not take it very seriously. When questioned about a possible American invasion, the Foreign Secretary, Geoffrey Howe, assured the House that he was ‘in the closest touch with the US and Caribbean governments’ and that he had no reason to think that American intervention is likely’.

Four hours later a tele-letter from the President to the Prime Minster made it clear that the Americans were in fact considering some kind of violent action. Reagan added: ‘It is of some assurance to know that I can count on your advice and support on these important issues.’ Thatcher replied that the UK was firmly opposed to any sort of foreign interference; almost before her message could have been received she was told that an invasion was being launched. ‘The British people’, observed Denis Healey, ‘will not relish the spectacle of their Prime Minister allowing President Reagan to walk all over her.’ The Prime Minister liked it even less, but she had to swallow it. When Sir Anthony Kershaw, Chairman of the House of Commons Foreign Affairs Select Committee, asked the President why he had not given Mrs Thatcher notice of his intentions, he replied bluntly: ‘Because I didn’t want her to say no.’

Even before this, the Falklands had provided Thatcher with evidence that Reagan was not to be relied on to provide the automatic support which she felt was her due. When an Argentinian invasion seemed imminent Reagan had assured her that he was urging General Galtieri not to indulge in any sort of military action. Once it became clear, however, that the Argentinians intended to ignore that advice, the Americans showed that they were as much concerned about their relationship with Latin America as with what Thatcher felt they should consider their oldest and most precious ally.

The Secretary of State, Al Haig, was despatched on a mission to cobble up some sort of compromise. Mrs Thatcher was first urged not to send a task force to reconquer the islands and then asked to stop or delay it in mid-ocean. If the Americans could persuade the Argentinians to withdraw, suggested Haig, would not the British agree to establish an interim administration under international authority and at once open negotiations on the issue of sovereignity? ‘Wooliness!’ exploded Mrs Thatcher ‘I did not despatch a fleet to install some nebulous arrangement which would have no authority.’ Did they think that she was another Neville Chamberlain eager to do deals with dictators?

Fortunately the Argentinians proved quite as intransigent as the British and refused to accept any sort of compromise. Fortunately, too, the Secretary of Defense, Caspar Weinberger, did not share his President’s doubts: ‘While the camera-hungry Haig jetted between continents in a search for peace, Weinberger simply got on with the business of making sure that Britain won the war.’

Grenada, the Falklands, a moment of panic when it seemed as if the Americans were prepared blithely to sacrifice Britain’s independent deterrent, strong differences of opinion over the attitude to adopt towards the Soviet Union: the limits on friendship were made embarrassingly clear to Mrs Thatcher.

But the friendship was there and was real. Thatcher’s patent delight at Reagan’s re-election in 1984, Reagan’s almost contemptuous dismissal of the Labour leader, Neil Kinnock, were not empty gestures but stemmed from a wish to help and support the other. The love-in at Reagan’s last State Banquet was almost embarrassingly fulsome. ‘She’s a world leader in every meaning of the word,’ declared Reagan, ‘and Nancy and I are proud to claim that the Thatchers are our friends.’ ‘You have been more than a staunch ally and wise counsellor,’ she responded. ‘You have also been a wonderful friend to myself and my country.’

Certainly there had been disagreements and differences of policy but the underlying respect and affection were real and significant. Far from being the weakest link in the Atlantic Alliance it was perhaps the strongest. Anglo-American relations have never been so close since Thatcher and Reagan retired from the scene.

Comments