There are two accounts of the negative effects for humanity of the explosion of generative AI: one minatory, one trivial. The minatory, the existential, version of it is that AI will poison the information ecosystems on which our democracies depend, crash our economies by doing a very large number of us out of a job, give every lunatic and terrorist the means to engineer novel pathogens at home, and administer the coup de grâce by sending terminators into our recent pasts and/or overstocking the cosmic stationery cupboard by turning all of us into paperclips.

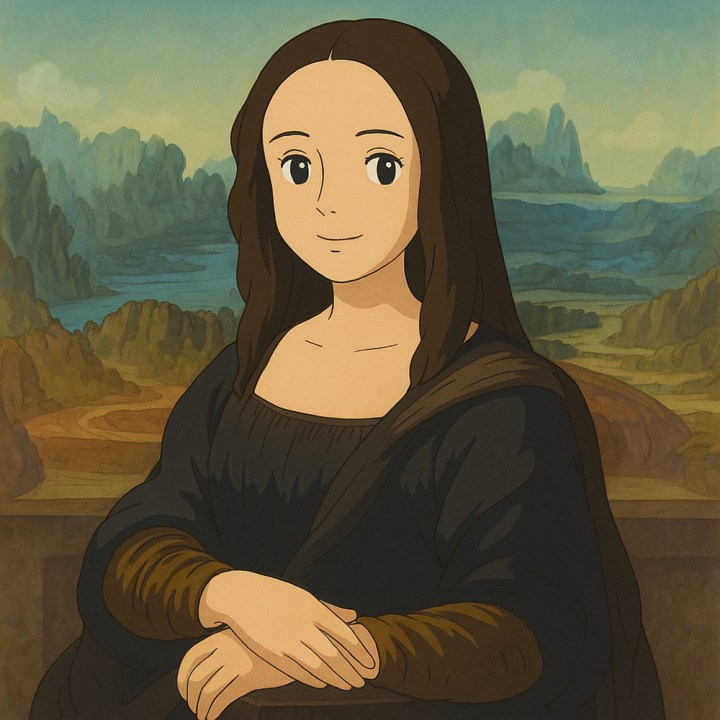

None of these scenarios shows any signs of imminently coming to pass, though since experts in the field take them seriously, we should too. But what we’re dealing with now is not the existential, but the trivial. I speak, of course, of the global proliferation of ChatGPT Studio Ghibli memes. Over the past few days, social media has been bombarded with AI slop in the ostensible style of the Japanese anime house. Famous scenes from films, iconic paintings, popular memes, user selfies – all have been turned into cutesy cartoons.

The White House has posted a whimsical Ghibli-style image of Immigration and Customs Enforcement agents arresting a weeping felon from the Dominican Republic; the Israel Defence Forces has announced chirpily ‘We thought we’d also hop on the Ghibli trend’, posting anime versions of IDF soldiers on patrol or flying fighter jets. OpenAI has said that the sheer number of Studio Ghibli requests is threatening to crash its vast server farms.

There are two things that, if we’re considering this from an artistic point of view, we must discount. But they very much should not be discounted when looking at the issue in the round. One is the obstinate point that to produce anything at all, generative AI needs to steal copyright material on an unimaginable scale. Studio Ghibli’s founder Hayao Miyazaki, who has called generative AI ‘an insult to life itself’, is having his life’s work scraped by bots so that tech billionaires can profit from it.

The other – which tech bros heavily invested in AI are very keen on sidelining or ignoring – is the environmental externalities. Generative AI soaks up a ridiculous amount of computing power, and it’s thirsty. The data centres producing your hilarious meme of a Studio Ghibli Khrushchev denouncing Stalin at the 20th Congress are drinking more groundwater every time you tweak it to give Khrushchev a slightly bigger nose. Is this half-thought-out meme honestly the best use of that water? If the last few humans die fighting Mad Max resource wars across a parched Earth, it’d be nice for the dignity of our species if we didn’t have to attribute it to giggling boomer uncles sharing stupid memes on Facebook.

But, as I say, leaving those things temporarily aside, there are purely artistic reasons to be depressed by what generative AI is doing to the culture. All these Ghibli images are not a way of making ‘creativity available to everybody’: they are a travesty of the idea of creativity, a branding consultant’s idea of creativity. The distinctive visual style of Studio Ghibli isn’t what makes Studio Ghibli Studio Ghibli. It is, rather, a metonym for a whole worldview, a whole species of narrative magic that we have come to associate with that production house. To mistake the visual style for the artistic product is the lowest sort of asininity. What ChatGPT is doing is erecting the golden arches above a building that hasn’t the slightest capacity to produce hamburgers.

The sheer number of Studio Ghibli requests is threatening to crash OpenAI’s vast server farms

Making creativity of this sort available to everyone is not to democratise art but to cheapen it. ‘Gatekeeping’ is, rhetorically, much disapproved of in our age. But gatekeeping has always been vital to art. Barriers to entry are a good thing. To take my own area of interest, by the time a book lands on the front table of Waterstones it has been gatekept multiple times. It must have convinced first an agent, then an editor, then an acquisitions meeting at a publisher, then the buyers for the bookshop, that it is something that people might reasonably part with money for. If it’s lucky, it will have been gatekept by the odd literary editor and the odd critic by the time it comes out too. Along the way it will have been improved by the attentions of several professionals – editors, designers, typesetters, proofreaders – whose full-time jobs depend on making books as good as they can be.

The digital age has removed some of those barriers to entry. Print-on-demand and self-publishing have made authorship available to pretty much anyone. That is no bad thing. All those gatekeepers are far from infallible. Some self-published books are terrific. One of the hottest things in fiction right now, Solvej Balle’s On the Calculation of Volume, was originally self-published. But in general, those barriers to entry, those gatekeepers, do help to raise the average quality. Pick a random self-published book and a random Random House book, and you can bet dollars to doughnuts that the latter is going to be better than the former.

The ultimate barrier to entry, the most important one of all, is the effort and commitment required to make a work of art at all. Self-publishing through Amazon is easy –but at least you had to write a book, however bad, before you could send it into the world. Exhibiting your watercolours of rural scenes to the world is now the matter of a moment – but at least you had to paint those watercolours, however bad, before you could do it. As everyone who has ever made something creative knows, the effort and time involved in making art plays a very large part in winnowing the good ideas from the bad. You discover that the idea that sounded cool when you blurted it out in the pub won’t sustain your interest, or the reader’s, over dozens of hours. You refine ideas, learn your craft, improve your technique.

The effort and time involved in making art plays a large part in winnowing the good from the bad

Generative AI has removed that last barrier to entry altogether. It requires next to no effort at all to turn your half-baked idea, or someone else’s (what if you took a famous image and rendered it in anime style?), into a simulacrum of an artwork in seconds. You don’t need to learn to cartoon, to immerse yourself lovingly in the original, to produce a piece of fan-art or a parody. You don’t need to think of what image or joke might work best. Just hammer out a quick prompt – ‘leatherface texas chainsaw ghibli’ – and hey presto, you’re a ‘creator’. Fast-forward a couple of years and ‘write me a new sally rooney novel’ seems to be a perfectly plausible follow-up.

The early promise of the internet wasn’t that it would fill the world with more rubbish (though that was an inevitable side-effect) – it was that it would filter it for us. It would make it searchable. It would help us find the good stuff amid all the dross. This promise, with the rise of generative AI, has been dramatically turned on its head. What we’re seeing with the Ghibli trend – as we did a year or two back when suddenly everyone was posting hilarious Wes Anderson-style clips – is a version of a frictionless future in which ‘creation’ requires no effort at all, and the results are worth exactly what the effort put into them suggests.

Here is one of the most powerful new technologies on the face of the planet – and we’re using it for a monkey-see, monkey-do stampede of half-hearted jocularity. Slop is flooding the zone. Kipple is driving out nonkipple. Being turned into paperclips, at this stage, is starting to look like it might come as a blessed relief.

Comments