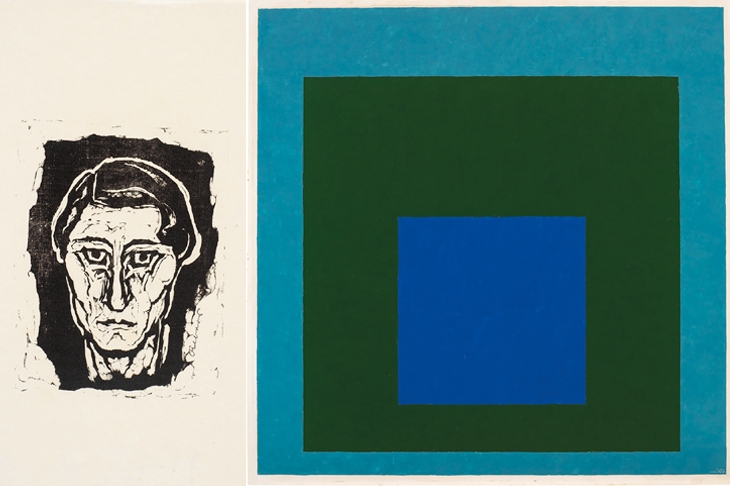

The German-born artist, Josef Albers, was a contrary so-and-so. Late in life, he was asked why — in the early 1960s — he had suddenly increased the size of works in his long-standing abstract series, ‘Homage to the Square’, from 16×16 inches to 48×48. Was it a response to the vastness of his adopted homeland, the United States? A reaction to the huge canvases used by the abstract expressionist painters in New York? ‘No, no,’ Albers replied. ‘It was just when we got a station wagon.’

In Charles Darwent’s new biography, Albers (1888–1976) comes across as a man as frill-free as the art for which he’s famous. Apparently, he held — and all too often shared — strong views about matters such as how beer must be drunk (hitting the back of one’s throat) and hot dogs be cooked (on a stick over a fire). Robert Rauschenberg, a pupil of Albers’s at Black Mountain College in North Carolina, called him ‘an impossible person’.

Not the most promising subject for a biography, perhaps. But that is to overlook two important factors. First, that Darwent (for many years critic on the Independent on Sunday) is a highly engaging writer on the visual arts. And second, that Albers lived through a remarkable period, mixing with some extraordinary people.

The first son of a painter-decorator, he was born in Bottrop, a country town in the north-west German region of Westphalia. Tuberculosis kept him from fighting in the first world war, but not long after it, he took up a place at the Bauhaus — where by 1923 he was appointed to the teaching staff.

Giving 20 hours of classes a week (compared to László Moholy-Nagy’s eight, Paul Klee’s five and Wassily Kandinsky’s three), he was the school’s busiest teacher. He found time, too, to make art of his own and was regularly seen picking over the rubbish dumps of Weimar, hammer in hand: his breakthrough works, the ‘Glasbilder’, were assemblages made from shards of broken glass.

Where Darwent really piques our interest is with the staff politics at the celebrated art and design school. Bitchiness and back-stabbing abound, perhaps most memorably in 1930 (by which time the institution had moved to Dessau) when Albers and Kandinsky contacted the city mayor to denounce Bauhaus’s then director, Hannes Meyer, as a communist. There was barely a shred of evidence, but Meyer was summarily dismissed all the same.

Three years later, the Bauhaus was forced by the Nazis to close, and Albers moved with his wife Anni across the Atlantic, both of them taking up an offer to teach at the experimental new arts college, Black Mountain. They’d spend the next 16 years there and miss most of the horrors that descended on their homeland — though, in an aside which Darwent frustratingly fails to expand upon, we learn that one of Albers’s Bauhaus students, Fritz Ertl, went on to become an architect for the SS and design the gas chambers at Auschwitz.

He also fails to explore Albers’s relationship with any of the avant-garde figures who taught alongside him at Black Mountain, from the composer John Cage and artist Willem de Kooning to the choreographer Merce Cunningham. The college is remembered today for its non-hierarchical approach to education, where there were no tests, no grades and everyone was considered equal. Not that that stopped Albers developing a dislike for its director, John Andrew Rice, and in 1940 demanding his resignation on the pretext of an affair with a female student.

This book is hard work, and not just to read — in his preface, Darwent admits it was a struggle to write too. How to deal with a subject who professed a ‘dislike of groups, kept no diary and batted away questions about his emotions or past’?

But certain problems are of the author’s own making. Anni Albers (currently the subject of a Tate Modern exhibition) was a textile artist of distinction and a major cultural figure, but here she is lamentably relegated to the sidelines. Also, for some strange reason, the book’s first 30 pages are dedicated solely to Josef’s ‘Homage to the Square’ paintings, consisting of three or four different coloured squares nested in one another. Yes, it was his signature series; yes, it’s impressive (he made 2,400 variations over the final quarter-century of his life). But a discussion of such technical matters as their hardboard support surely isn’t a way to grab readers’ attention from the off.

Rightly or wrongly, Josef has gone down in history as Albers the austere, the exemplar of a rigorous Bauhaus modernism — and there’s little in this biography to change that.

Comments