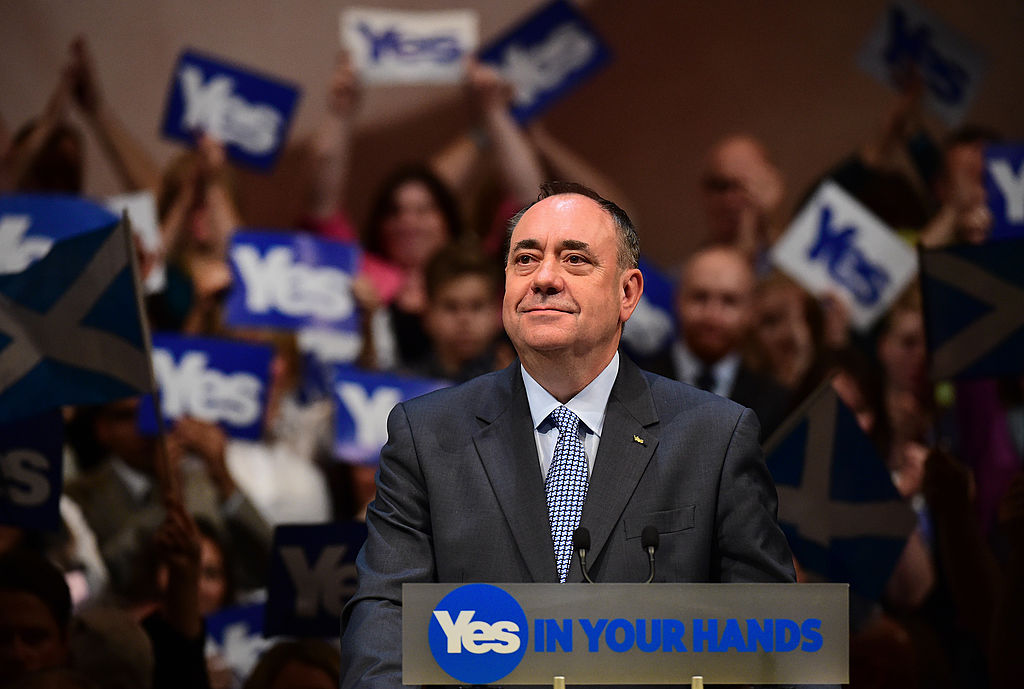

Just hours before he passed away, Alex Salmond tweeted that ‘Scotland is a country, not a county’. It was a response to First Minister John Swinney’s participation in the Prime Minister’s Edinburgh summit at the weekend – and Salmond smelled a rat. A phalanx of English regional mayors being given equal prominence to his country’s FM didn’t work for him. He likely would have refused to attend had he still been in post, or at least created such a stink beforehand that his role in proceedings would have been enhanced. Somehow or other, he would have sent a message to the people of Scotland that he was on their side against the English machine.

Salmond had a political and strategic intellect which established him as the pre-eminent Scottish politician of my lifetime. Indeed, along with Margaret Thatcher, Martin McGuinness, Tony Blair and Nigel Farage, I would regard him as one of the five most impactful domestic politicians of the last half century. The former SNP leader has done that which will never be undone, causing change which will never be reversed. In almost all the analysis we have seen since his death on Saturday, commentators have asked and answered the question of what Salmond’s legacy will be. Yet Salmond’s legacy is not something we will wait to experience some time after his passing – we are already living through it.

One could make a reasonable, even compelling, argument that the SNP’s victory in the 2007 Holyrood election could have been achieved by another leader. With 32.9 per cent of the vote share and a one-seat victory over a tired Labour Party, it was hardly unattainable. However the victory four years later was on a scale only achievable by a generational talent, the sort of political force who could persuade almost half the country to support a nationalist party when only around one-quarter of them were, at the time, nationalists. Salmond’s pragmatic competence persuaded unionists to trust him, before he turned them into real nationalists three years later when he almost won the independence referendum. That the SNP remains in government today, 17 years after he walked through the doors of Bute House, is itself a legacy of Alex Salmond.

That the SNP remains in government today, 17 years after he walked through the doors of Bute House, is itself a legacy of Alex Salmond.

That living legacy extends beyond the SNP, to the very fabric of Scottish governance. The devolution of 1999 is not the devolution of today. Salmond’s victory in 2007 spooked unionists into the creation of the Calman Commission – opposed by the SNP – but leading to the UK government passing the Scotland Act 2012. That Act, passed after Salmond’s majority victory in a proportionally representative parliament, was classic reactionary constitutionalism. It was the devolution of a limited set of mainly tax powers that was thought sufficient enough to buy off pro-Scottish unionists and halt the advance of Salmond.

But it wasn’t. Next was the famous ‘Vow’ – a panicked reaction to a poll the weekend before the 2014 referendum which showed Yes winning. This in turn led to the announcement of the Smith Commission the day after the narrow No vote, to fulfil this ‘Vow’ that had promised more devolution to Holyrood if people voted against independence. That Commission produced the Scotland Act 2016, a more significant Act than its predecessor four years earlier. As well as further taxation powers and additional control over welfare, it created the ‘fiscal framework’ and devolved the Scottish Crown Estate, which now controls the destiny of offshore wind and tidal energy, the future economic backbone of the country.

The British state has responded to Salmond at every turn – chasing him down every street and up every alley. And he was not slow to point out that since his departure after the referendum, the momentum slowed to a standstill. Salmond’s legacy is not to be determined by whether or not Scotland becomes independent – it is in the extent of the powers devolved to Holyrood over the last 25 years.

That’s not all though. Salmond’s vision for his party and his country – despite in his last years becoming leader of the rival pro-independence Alba party – encouraged others to push back against forces that had began to chip away at the SNP. The Scottish National party’s rejection of the Green coalition and its reacquaintance with pragmatic centrism under Swinney and Kate Forbes (what might one day become known as Salmondism) has echoes of how Salmond once governed the group. The former first minister’s legacy is in the crippling uncertainty Scottish Labour has been left with about how to prove the party can be Scotland’s voice at Westminster and not Westminster’s voice in Scotland. And Salmond’s smart politicking has resulted in the Tory’s 15-year internecine war about whether its Scottish Conservative group should even exist, such is its perceived malfeasance in Scotland.

Scotland doesn’t need to wait a decade to figure out Alex Salmond’s legacy. We’ve been dancing to his tune for years.

Comments