It is easy to take the art and antiques fair for granted. After all, thousands of them take place every year, from humble events in village halls — cardboard boxes, old newspaper and cups of tea — to fairs so glamorous that on opening nights the ticket alone can cost $5,000. It was not ever thus. That revered mother of all such selling exhibitions — what became known as the Grosvenor House Art and Antiques Fair — was conceived in 1934 as a daring initiative to stimulate trade in the dark days of post-Depression London. As for the word ‘fair’, the late and much-lamented Frank Davis, who was still writing his Country Life saleroom column aged 97, recalled in 1961 that the very use of the term had caused unease when first mooted. Critics were concerned that its ‘undertones of popular, carefree amusement might give an impression of raucous irresponsibility, far removed from the cloisteral calm traditionally associated with the acquisition of works of art’.

Who could have guessed that this fair formula should prove so popular? Or that it would move from a one-off ‘stimulus’ for the art trade to its sharpest weapon in its fight for survival as the all-powerful auction houses continue their relentless incursion into the retail art business. Those Thirties trailblazers got it just about right, however, when they decided to call their exhibition a fair, for what have most of these top events become if not marketplaces and meeting places accompanied by perfectly medieval carousing, amusements and entertainment? There may never have been any dancing bears but even the otherwise sober Maastricht fair has its wandering purveyors of beer and oysters.

And The European Fine Art Fair in Maastricht — it acquired its hideous acronym TEFAF in 1996 — is without doubt the greatest of all art and antiques fairs. Absolutely no one expected that to happen. This year, it celebrates its Silver Jubilee (March 16–25), and it seems an opportune moment to consider just how a once small fair in a once small town few had heard of before the eponymous Treaty could become — and remain — the world’s pre-eminent art and antiques showcase.

For art fairs tend to come and go, and the fortunes of those that do survive often rise and fall like a rollercoaster. This has not been the case at Maastricht. The principal reason, perhaps, is that it, uniquely, has always been a fair run by and for dealers, with no outside fair organiser calling the shots or taking a profit. Its dealer committees have continually, restlessly honed the fair formula — improving, refreshing, expanding the range of exhibiting galleries, and broadening its global draw. Crucially, from the start this most professional of fairs has also invested heavily in ensuring the quality and authenticity of works on display. Which other fair can boast 29 specialist vetting committees comprising 179 international experts?

When TEFAF was founded in 1988, the great fairs of the world — all of which could be counted on one or possibly two hands — were mostly in London, Paris and New York. Today, it can be no coincidence that out of the hundreds of successful fairs that have spawned over the decades just two tower above the rest, and neither one is in a capital city. Unlike their grander predecessors, the modern and contemporary art fair Art Basel and TEFAF are staged not in elegant period buildings in cities that collectors might be visiting anyway but are so-called ‘destination fairs’. They offer dealers the opportunities of huge and inexpensive stands in exhibition and convention centres — and none of the countless distractions of New York, London or Paris for their visitors.

For today’s clichéd cash-rich, time-starved collector, it seems that this kind of huge-scale concentration — of art, academics, curators and collectors — is just the ticket. People like having a choice, and making their choice — creating their own ‘pick ’n’ mix’ fair experience of objects and people. The difference between the two events, of course, is that Basel offers only modern and contemporary art — and increasingly less of the former. The joy of Maastricht is that this vast sweet shop has the best of everything: antiquities, antiques, haute joaillerie, design, books and manuscripts, Old Masters, modern and contemporary art — ranged not in jars on shelves but along ‘streets’ named after the great shopping boulevards of the world. Clients expect every leading dealer to be there, and relatively few serious collectors are not.

This great feast really does result in cross-fertilisation. TEFAF chairman Ben Janssens, for instance, a dealer in Chinese works of art, each year sells to new clients who came to the fair in pursuit of something else. Antiquities dealers, similarly, have benefited from their new position next to modern art. For in an art world dominated by the modern and contemporary, it is easy for people to forget — or not even realise — that there are other things out there they might like to live with.

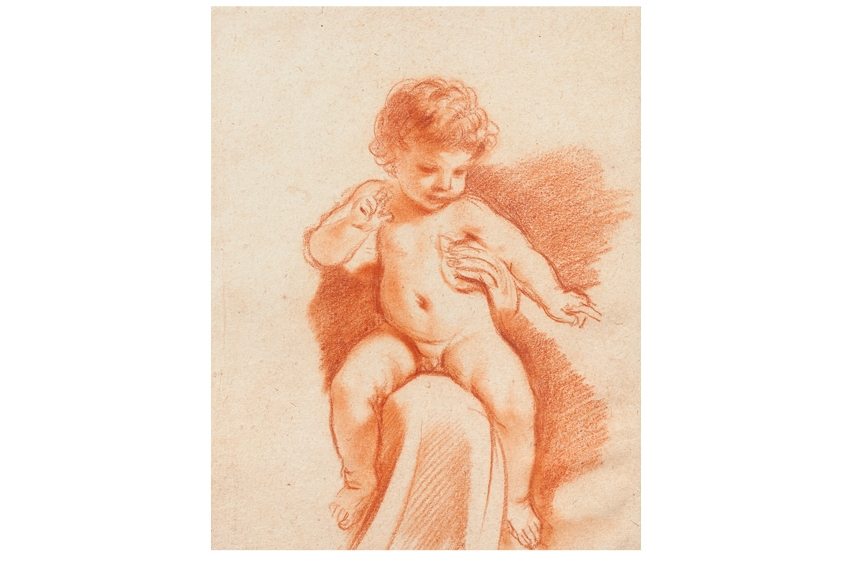

So, what can TEFAF’s 73,000 or so visitors expect this year? Beside 260 dealers from 18 countries offering some 30,000 works of art, there will be great Old Master drawings from the Fondation Custodia in Paris on loan, as well as the first-ever BMW Art Car, with bodywork designed by sculptor Alexander Calder in 1975. Oh, there will also be a restaurant, a brasserie, cafés, sushi and champagne bars.

www.tefaf.com

Comments