‘In science, truth always wins,’ said the molecular biologist Max Perutz. In 2022, Charles Piller, an investigative journalist for Science, published an article posing a new set of obstacles to Perutz’s truism. He revealed cases of fabricated data in the area of Alzheimer’s research, setting off a cascading set of consequences for the researchers involved and for the field more generally. Doctored details how the dossiers of evidence were compiled in the lead-up to the publication of that 2022 article and the subsequent fall out.

The central character is Matthew Schrag, a scientist at Vanderbilt University, who provided the expert analysis for Piller. The book is centred on the developing relationship between Schrag and Piller and interwoven with interviews with research scientists and people affected by Alzheimer’s. It is an account of a story that has been playing out recently in universities, journals, biotech companies and peer review platforms, but has been largely unnoticed by the public.

Piller and Schrag exposed in detail two cases where scientific data showed evidence of manipulation over many years. The first was a series of papers by the academic behind Cassava Sciences, a company that produced an experimental Alzheimer’s treatment. The second had at its heart a post-doctoral researcher, Sylvain Lesné, working at the University of Minnesota, who in 2006 reported a previously undetected form of beta-amyloid.

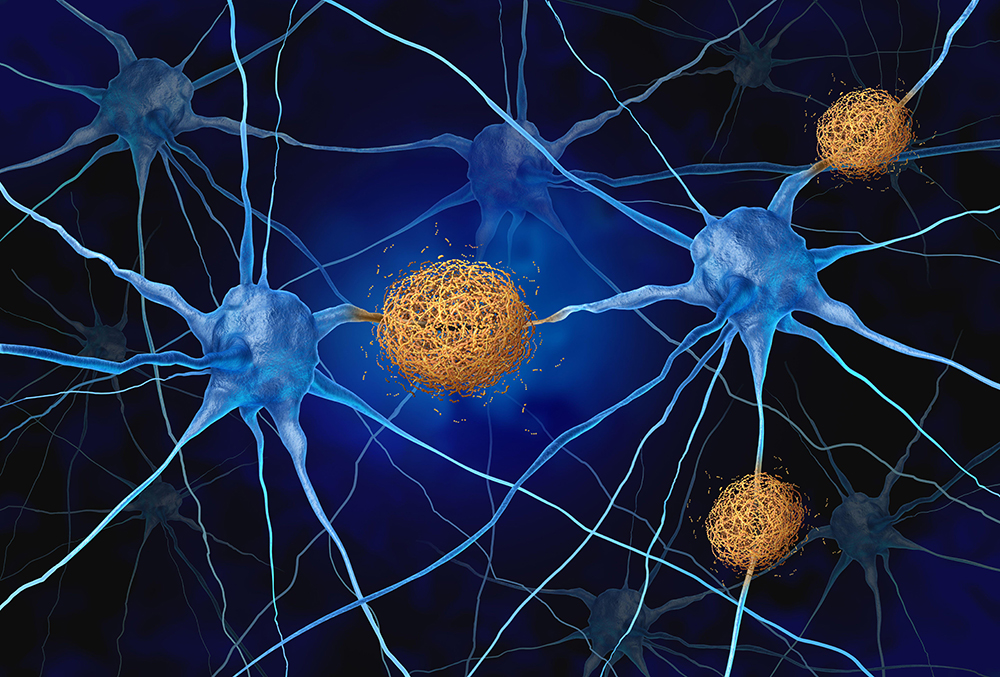

Beta-amyloid is one of the proteins that form clumps in the brain during Alzheimer’s, proposed under the ‘amyloid cascade hypothesis’ to trigger an unstoppable avalanche of events ultimately leading to the death of brain cells and the accompanying hollowing out of memory and selfhood.

The new form detected by Lesné, termed Aβ*56 (pronounced A-beta-star-56), appeared especially toxic, making it a prime candidate for targeting with new therapeutics. But multiple instances of data manipulation were found in Lesné’s work, rendering the discovery of Aβ*56 uncertain. The paper was ultimately retracted, but not before a drawn-out investigation, and two years after the publication of Piller’s revelations in Science. In both these cases, Piller details how corporate, regulatory and institutional interests swung into action to protect reputations, and, in the Cassava instance, shareholder value. This is clearly condemnable, and all credit to Schrag, Piller and others for bringing it to light.

But Piller goes on to suggest that the amyloid cascade hypothesis, which has held sway as the mechanism driving Alzheimer’s disease since it was proposed by John Hardy and Gerald Higgins at UCL in 1992, has been defended by a scientific ‘mafia’ that has starved other areas of research of the funding they deserve, leading the field to a scientific dead end. While there may be some truth to the under-representation of other areas of pursuit in research budgets, the evidence of amyloid’s role (or at least the gene that encodes it) is overwhelming, and there is a notable absence of the countervailing arguments in Piller’s account. It is not for nothing that the amyloid cascade hypothesis has endured, even if its ultimate form contains nuances well beyond its original articulation.

Doctored appears at a time of intense discussion surrounding the recent product of the amyloid cascade hypothesis, a new generation of medicines that clear amyloid from the brain. Though highly effective at destroying their target, these drugs come with the risk of severe side effects. Piller delves into them and, through interviews with experts in the field, finds cause for pessimism about their efficacy and safety in treating Alzheimer’s. However, there is again an absence of balance in his account. It is true that these drugs are by no means cures for Alzheimer’s, but the demonstration that removal of amyloid from the brain can reduce the rate of disease progression is a scientific turning point (even if not a medical one) for the amyloid cascade hypothesis that is not fully acknowledged.

Multiple instances of data manipulation were found in Lesné’s work, rendering his findings unsafe

Piller’s account of the Alzheimer’s field is bleak, and in specific places deservedly so, but overall does not convey the ongoing causes for optimism. Historically gaining a fraction of the budgets of other areas such as cancer, Alzheimer’s research has made major strides in the understanding of the underlying biology in recent years. This includes the genetic risks, the basic mechanisms of pathology and a broadening of the scope beyond amyloid.

The first signs of disease-modifying treatments, underpinned by work in the 1990s and 2000s, are tantalisingly close if not already here. Dozens of experimental drugs based on more recent research, testing numerous scientific hypotheses, are in the pipeline. Large datasets arising from initiatives such as UK Biobank are only just beginning to be tapped for their potential.

More widely, the recognition of Alzheimer’s as a disease and not simply a symptom of old age has brought focus to the problem. There are now many scientists chipping away at the edifice of the disease and finding chinks that might be exploited for therapies. Piller’s final chapter does illustrate some of these promising leads that may prove decisive, but a full picture does not emerge.

The book is a compelling account of the unravelling of scientific fraud. The description of the detective work in the build-up to the Science article is where it excels. However, these examples do not represent the state of field as a whole and the book does not go far enough to express this. What is uncontroversial, however, is that the eventual cures will rely on robust science and truth winning out. In the words of Schrag: ‘You can’t cheat to cure a disease. Biology doesn’t care.’

Comments