In a couple of weeks, Alan Bean will turn 80. He’s not planning any special celebration. If he does go out, it will probably be to a local restaurant in Houston, Texas. ‘I’ve eaten barbecue at this restaurant once a week, have done for 15 years,’ he tells me. ‘Nobody there has any idea that I’m anyone other than this old guy who likes barbecue.’

Few people even recognise his name. This is probably because Alan Bean was the fourth man to do something. His late colleague Pete Conrad was the third man to do the same thing — and no one used to recognise him either. The first two were Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin.

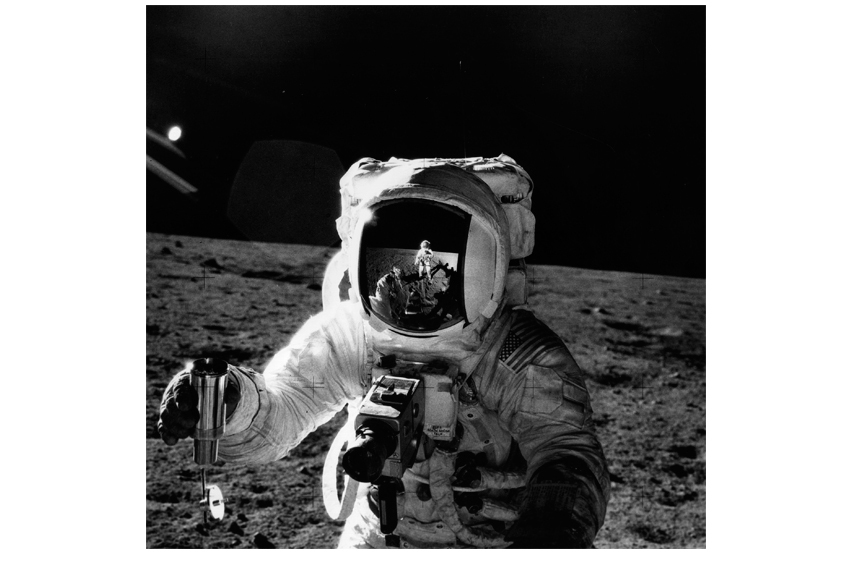

Apollo 12, sandwiched between the epic first of Apollo 11 and the famous disaster of Apollo 13, has been largely forgotten. Which is a great injustice, because of all the moonwalkers Bean and Conrad are the most interesting, the men who concentrated more on the emotional impact of their experience than the whizz-bang technicality of it all. Their story literally isn’t rocket science. For Bean, the quarter-million-mile journey to the moon turned out to be more about the Earth. Standing on a lump of rock, looking back at his fragile planet, he realised how much he valued it.

‘Since then I have not complained about the weather one single time,’ he says. ‘I’m glad there is weather. I’ve not complained about traffic — I’m glad there are people around.’ On his return, he used to visit shopping malls just to ‘watch the people go by. I’d think, boy, why do people complain about the Earth? We are living in the Garden of Eden.’

Instead of regretting the things he can’t change, Bean finds satisfaction in what gifts he does possess. ‘When you see other people achieving success and you’re not, you say, what is it? Is it talent or is it something else? You don’t want it to be talent, because then you’re stuck. You say, I’m 6ft 4in but I’ve always wanted to be 6ft 8in — well, then you’re screwed. I wanted always to be something you can accomplish with determination and persistence.’

Bean was rejected in an early astronaut selection round, and only got a crack at the moon because someone else died in a plane crash. So hard did he train that for the final few months he deliberately forgot people’s names as soon as he was introduced to them at parties, lest the information crowd out something he needed for the mission. When he got to the moon he deliberately left his silver Nasa badge there, safe in the knowledge that the mission had earned him a gold one.

These attitudes have carried through into Bean’s second career, as an artist specialising in paintings of the lunar landscape. ‘Mostly you don’t go up in a straight line. I’ve noticed in art it’s more like steps. One day you can do something, then the next day you can’t, then all of a sudden three weeks later you do it again and you make the next step.’

Again, it’s about the desire to do his best rather than obsess about achieving perfection. ‘I’d like to be the greatest artist in the world — it’s not like I imagine I’ll ever be that, or even close — but it’s a dream. I think the difference between those who have achieved quite a bit and those who haven’t is that they’re willing to do it again and again and again.’ Bean’s paintings now fetch hundreds of thousands of dollars. But all the time he’s trying to force the change, try new things to see where they lead. It’s an approach, he says, that wouldn’t have gone down well at Nasa. One innovation is applying texture to his pictures with tools he used on the moon. ‘I think that’s one of the best things I’ve ever done for my art. But if I’d gone to my boss Deke Slayton with that idea, he wouldn’t have let me do it. “Nobody else ever did that,” he’d have said. “Monet didn’t do that, Rembrandt sure wouldn’t have done it. What’s wrong with you, Al?”’

This habit of confounding expectations is what makes Bean so fascinating. He maintains, for instance, that his proudest achievement as an astronaut wasn’t going to the moon, but the two months he spent working on the Skylab space station. ‘It was harder. It’s harder to work in a coal mine day after day after day and do your best than it is to go on a trip to Paris and do your best.’

Bean also accepts that people will inevitably be more interested in those two days he spent on our nearest celestial neighbour back in November 1969. Unlike on other Apollo missions, he and Conrad were the best of friends, doing a job as well as they could while never taking it over-seriously. On the way to the moon they danced weightlessly to ‘Sugar Sugar’ by the Archies. The pasta-loving Bean requested that Nasa pack him freeze-dried spaghetti. ‘I did that so I could be the first person to eat spaghetti on the moon. And I was, thank God — I watched Apollo 11 hoping that Neil or Buzz wouldn’t do it.’ Conrad, famous for always wearing a baseball cap, had a giant one made to fit over his space helmet. In the end he was unable to smuggle it on board, scuppering his plan to surprise Nasa officials during the moonwalk by appearing in shot with it on.

Bean plans to do a painting of how it would have looked. ‘I talked to Pete’s wife the other day — she thinks she has the cap in storage somewhere.’ As ever he is looking forward rather than back, treating life as a continuing adventure, rather than just needing its ends tied up. ‘Each journey takes up 98 per cent of your time, the destination only 2 per cent. It feels good at the destination, but then immediately you set out on a new journey. You do think back about the previous accomplishment: it feels good to think about being the fourth man on the moon. But mostly I’m wishing I could paint better.’

Throughout our conversation, Bean shows himself to be a man attuned to life’s contradictions, rejecting certainties, aware that the grey areas are where things get interesting. ‘I have learnt in life,’ he says at one point, ‘that almost anything you say is just your opinion. It’s not a fact.’

There’s something very appealing about a man less sure of things at 80 than he was at 20. Alan Bean is an anti-Buzz Lightyear, a rejection of fictional ideas of a space hero. The reality is far more impressive.

Comments