Andrew Lambirth on John Leech, artist friend and travelling companion of Dickens, whose pictures help illuminate the novelist’s work

Christmas approaches, and my thoughts turn, with reassuring inevitability, to Dickens. As the nights draw in and the winter winds blast across the fields of East Anglia, the counter-urge is for the comfort of a good book, to be read preferably by the fireside in a snug armchair. Dickens is the high priest of cosiness, forever creating situations in which the fire and wine within are contrasted with the cold and storm without. In his novels, hearth and home are crucial images of goodness, comfort and continuance, and nowhere more so than in his first and greatest festive story, that indisputable classic, A Christmas Carol.

Dickens, always an intensely visual writer, sets the scene: ‘The fog came pouring in at every chink and keyhole, and was so dense without, that, although the court was of the narrowest, the houses opposite were mere phantoms. To see the dingy cloud come drooping down, obscuring everything, one might have thought that nature lived hard by, and was brewing on a large scale.’ In the cold darkness is the pale glimmer of Scrooge’s mean fire over which he huddles and eats his gruel. Evidently, he has yet to honour his fireside. Here, as a prologue, he is visited by the ghost of Jacob Marley, his deceased partner, who appears dragging a chain of money boxes.

Marley has come to save Scrooge. To this miserable old sinner’s home is brought a drama in three acts as the Ghosts of Christmas Past, Present and Yet to Come visit him and show him scenes that he finds inexpressibly moving. The shadows of the past and of the future overwhelm his ingrained misanthropy. The miser is thawed and his moral regeneration achieved: rejoicing breaks out in his heart, and the selfish, avaricious killjoy is replaced by that generous celebrant of life, the Dickensian figure of an ideal Christmas, in which all the world becomes an extended family and feelings of benevolence are engendered by an awareness of one’s own good fortune and comfort.

Although Dickens drew unforgettable pictures with words, from the start his books were accompanied by a range of illustrations by some of the best graphic artists of the day. Chief among these was the distinguished Punch cartoonist, John Leech (1817–64), who became a good friend of Dickens, along with Mark Lemon and Henry Mayhew, joint founding editors of Punch. These men, known as the Punch Brotherhood, spent a great deal of time together, and Leech often accompanied Dickens on the restless writer’s trips in England or abroad. It was with Leech and Lemon that Dickens visited Norwich and Yarmouth in 1849, afterwards walking from Yarmouth to Lowestoft and back, an excursion which so fired the writer’s imagination that it resulted in key episodes in David Copperfield.

Leech was a master of what might be called ‘delicate’ satire, and was instrumental in leading Punch away from radicalism towards conservative commentary. His work was immensely popular — Trollope said Punch’s success was due to Leech more than to any other individual — and he was probably the best-known English artist of his time. When he died, Millais said of him: ‘Very few of us painters will leave behind us such good and valuable work as he has left. You will never find a bit of false sentiment in anything he did.’ (And Sickert tartly observed: ‘Millais had the benefit of Leech’s friendship, but his example taught him nothing…’)

Leech’s gentle irony infused a visual language that was deliberately measured and thus readily acceptable to the average Victorian householder. It was not savage and explosive satire, but subtle and well judged. Leech, who had briefly studied medicine, possessed satire’s equivalent of a soothing bedside manner: he was the reassuring GP rather than the surgeon who wielded the knife.

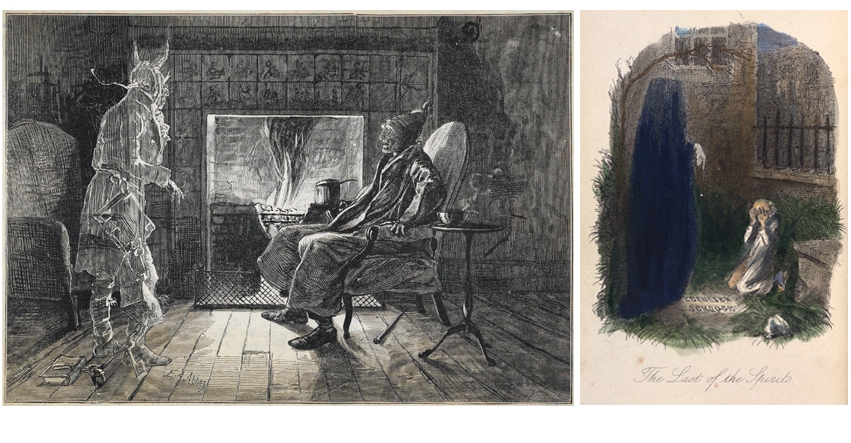

Although A Christmas Carol was published by Chapman & Hall, Dickens’s dissatisfaction with the company led him to take on himself the expenses of the production. Perhaps unwisely, the first edition was a rather lavish affair, illustrated with four full-colour etchings by Leech with an additional four black-and-white woodcuts. It sold well but did not initially make Dickens the fortune he had hoped.

Leech excelled himself in these illustrations. The etching of ‘The Last of the Spirits’ is a superb and moving image. Leaving aside the character and economy of the drawing, Leech’s use of colour is highly effective: the midnight blue of the Spirit’s robe both darkens and warms the composition, adding emotional depth but also a suggestion of hope. The greys and blacks of the night graveyard are gentled with touches of brown and green (intimations of spring and rebirth), while patches of paler blue at the top suggest the approach of dawn. The tiny huddled figure of Scrooge is penitent before the awful inhuman presence of the Spirit with its down-pointing finger. (Surely a witty reference to the upward-pointing gesture of Old and New Testament prophets in Renaissance iconography.)

The plot of A Christmas Carol was constructed while Dickens roved the streets of London for as much as 15 or 20 miles a night. He was deeply involved in the actual writing of it and confessed that he wept and laughed throughout the six weeks it took him. When the book was published it sold 6,000 copies in its first day. Thackeray, uneasy friend and close rival, told Dickens that it had done a ‘national benefit, and to every man or woman who reads it a personal kindness’. Lord Jeffrey, literary critic and founder of the Edinburgh Review, wrote to Dickens that he had done more good than the Christian Church could in a whole year. And apparently an American factory owner gave his employees another day’s holiday after reading it.

More than 100 years ago G.K. Chesterton wrote: ‘Whether or not the visions were evoked by real Spirits of the Past, Present, and Future, they were evoked by that truly exalted order of angels who are correctly called High Spirits. They are impelled and sustained by a quality which our contemporary artists ignore or almost deny, but which in a life decently lived is as normal and attainable as sleep, positive, passionate, conscious joy. The story sings from end to end like a happy man going home; and, like a happy and good man, when it cannot sing it yells. It is lyric and exclamatory, from the first exclamatory words of it. It is strictly a Christmas carol.’

Scrooge is the embodiment of accountability: his behaviour can alter society for better or for worse, and the book’s conclusion is so heartening because his personal redemption means the improvement of the condition of others. The material is not opposed to the spiritual in the book, only the wrong attitude to material things is shown to be harmful. When matter and spirit work together, the outcome is seen to be joyful. In part Dickens’s tale of a redeemed miser is effective because he himself understood so clearly the power of money, being a self-made man from an impoverished background. There’s definitely an element of ‘there, but for the grace of God, go I’ in his delineation of Ebenezer Scrooge.

At Christmas begins the cycle of life. The Christian year starts with Christ’s birth, and the celebration of this special event builds upon the foundations of the midwinter pagan festival of lighting bonfires and decorating the dwelling with evergreens, to ensure the return of spring. In Dickens’s version, the rules of both pagan and Christian festivity are observed. Christmas is not just a time for feasting and shutting out the dark, but also for praying and considering others — a singular combination of religion and merrymaking. Dickens composed an appeal for charity and mirth and delivered it through his Ch

ristmas stories to his readers, intimately and directly, seated as they were before their festive logs, digesting turkey and plum pudding. Its powerful emotional impact mixes fantasy, religious mysticism and popular superstition. And thus we begin to understand what Chesterton meant when he wrote: ‘Dickens did not strictly make a literature; he made a mythology.’

The exhibition A Hankering after Ghosts: Charles Dickens and the Supernatural is at the British Library until 4 March.

Comments