What on earth does George Osborne know about journalism? How can someone with no journalistic experience go straight in as editor – editor! – of the London Evening Standard? What were its proprietors thinking? To have dinner with an MP is one thing, but to hire him as an editor? And what does this sacked politician know of the demands facing an editor in the digital era? How can he combine such a demanding job with his duties in parliament and towards his constituents in Tatton? If I wasn’t an editor, these might be a few of my reactions to the extraordinary news today. But much as I hate to admit it, this appointment might actually work.

I was rather rude about George Osborne throughout his frontbench career, and regarded him as a deeply disappointing Chancellor. But I will say that he is an unusually good writer, perceptive and funny. When he filed his diary for The Spectator’s Christmas edition, it was one of the best articles in one of our best editions. So let’s not pretend that he has no journalistic talent. In fact, I suspect he’s rather better at writing than he was running the Treasury.

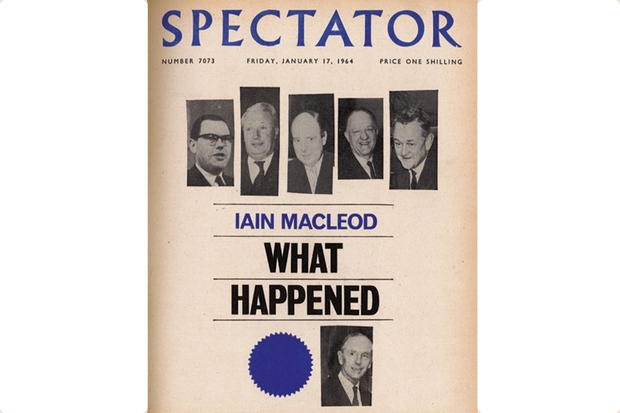

Nor is he the first ex-Cabinet minister to become an editor. Among their number is Iain Macleod, who took over The Spectator in December 1963. At the time, it was asked: how could this work? Would this former minister use The Spectator to undermine the Prime Minister and plot his own way to No. 10? The Spectator’s then deputy editor, Anthony Hartley, resigned in protest at a serving politician being appointed to such a job – but Macleod made the conversion quite well. He put his formidable political contacts to work on behalf of the readers and wrote perhaps our best-ever front story: the Magic Circle, about the real machinations of the Tory leadership contest. A framed copy of that cover sits on my desk.

Richard Crossman, who had been a minister in Harold Wilson’s government, followed the same path and edited the New Statesman but was seen to be far less of a success than Macleod. The main problem Macleod caused at The Spectator was his being so miserable that he killed the party: unlike Osborne, he was no social butterfly. He did commission articles from his political mates, but far more importantly he appointed Alan Watkins, one of the greatest writers in The Spectator’s history, as our political editor. Watkins was a socialist, and a genius (he regarded Macleod as being ‘very close to being a real writer’). Macleod sat out the 1965 Tory leadership contest, biding his time. When appointed shadow chancellor, he left the magazine. His editorship had been brief, but pretty accomplished. And succumbed to none of the traps that his enemies had predicted when he took the job.

The other question Osborne faces is whether he can be a part-time editor. Pretty much everyone else who is an editor is on that chair an awful lot, the industry evolution making ever-greater demands. But Boris Johnson was a part-time editor of The Spectator and an immense success. Boris had then, and has now, a gift for hiring brilliant people in whom he inspires complete loyalty – and had a brilliant deputy in Stuart Reid. Good editors get results, create a lively publication that people find unmissable. They can be done by Paul Dacre-style involvement in page layouts and headlines, or it can be done with a Boris-style light-and-deft touch. So we can’t say that Osborne will be a failure because he’ll be part-time.

And Boris did encounter one rather large problem in his editorship. The editor is legally and personally responsible for every word in the publication. If The Spectator were to run a libel when I was off, I’d take the rap, go to court, offer my resignation – unlike politics (or the BBC) there’s no dodging accountability, no asking for junior heads to roll. That’s how editing works, and quite right too: it focuses the mind, it creates the line of responsibility. The sword of Damocles hangs above every editor’s chair. So when The Spectator ran a leader being rather rude about Liverpool, Boris Johnson was blamed for every word. As editor, he could hardly say ‘I didn’t write it!’ – and to his credit, he didn’t attempt to make any such excuse. He was sent up to Liverpool on a penitential tour. So things did get difficult, especially when The Spectator started to dump on his then party leader, Iain Duncan Smith. When Boris was made education spokesman, he decided – as Iain Macleod did before him – that he could not combine editing with a front-bench job.

Osborne will be held responsible for every word in the Evening Standard. If a columnist sneaks a fruity phrase into the newspaper, then he’ll have to take the blame.

The harder question he faces is a rather simple one: to whom do his loyalties lie? Boris Johnson was a journalist who went into politics: he embodied The Spectator’s virtues. He fought for the reader, even if that meant complicating his own career. Macleod had the restraint not to use the editorship for political games. But will the same be true for Osborne, one of the greatest schemers in Westminster? Will readers be treated to op-eds by David Cameron and Nicky Morgan? Leaders chastising Theresa May for not using the phrase ‘Northern Powerhouse’ or urging the government to press ahead with HS2?

Let’s not forget that the Evening Standard is the newspaper of a Labour-leaning city (in my view, it should not have endorsed the Tories in the last general election). Theresa May is less popular in London than in any other part of the UK, Scotland included. To shape this great newspaper into a Tory mouthpiece would be a betrayal of its readers: people whom Osborne is now paid to serve.

Newspaper editors run benign mini-dictatorships: will Osborne be able to resist using his for his own schemes? This is the challenge. But he has, in Ian Macleod’s editorship of The Spectator, a good model to follow.

PS Whether Osborne’s new job is good for his constituents is another matter entirely. He should have quit, as Tristam Hunt did. The Spectator is a weekly; the Evening Standard is daily and editing it is incompatible with a serious commitment to a northern constituency. Iain Macleod represented Enfield and Boris Henley – both commutable from London. Also Boris stood for parliament while he was Spectator editor: his constituents knew the deal. If Osborne were standing for Tatton, would the editor of a London newspaper in the pay of a hedge fund even get on the shortlist? The risk Osborne presents – to his party and parliament – is underlining the impression that young MPs see public office as a stepping stone to self-enrichment. As a journalist, he may well work. As an editor, I won’t say he’s doomed. But as a politician, I think he’s finished.

Comments