In 1982 Sven Berlin placed a sealed wallet labelled ‘Testament’ on top of a rafter in his studio with instructions for it not to be opened before his 100th birthday on 14 September 2011. Inside was a key to the identities of the characters in his notorious roman à clef about post-war St Ives, The Dark Monarch, published 20 years earlier and immediately withdrawn after four of those characters sued for libel. None of them was a major artistic figure and by today’s standards the libels were laughable, but Berlin’s exposure of the petty politics behind the St Ives idyll — which he later compared to ‘going for a bathe and swimming into a shoal of barracudas’ — caused permanent damage to his artistic career.

A self-taught sculptor who had dropped out of art school to partner his first wife Helga as an ‘adagio’ dancer on the music-hall circuit, Berlin was more attuned to the Primitivism of early Epstein and Gaudier-Brzeska than to the formal abstraction of Nicholson and Hepworth that came to dominate the St Ives School. In 1950 he resigned from the Penwith Society of Artists in resentment at the rejection of his figurative carvings by a hanging committee which, he felt, regarded him as a throwback, ‘a drunken helot and …an obsolete romantic always getting into fights, cutting huge boulders of stone into the night’.

Like that other piratical autodidact Paul Gauguin, Berlin responded to rejection by making a grand exit into self-imposed exile. In 1953 he departed for the New Forest in a horse-drawn gypsy wagon with second wife Juanita, new baby Jasper and three children from previous marriages. After a punishing first winter camping in the Forest alongside the gypsies of Shave Green, the family upgraded to a collection of huts in a rented field, then a wooden chalet and finally a farmhouse at Emery Down, where Berlin grew into the role of great British bohemian.

In the 1950s he showed with Epstein and Frink in Davies & Tooth’s exhibitions of Important Contemporaries; in 1960 John Boorman made a film about him for the BBC. But today his art is largely forgotten, and it has fallen to the enterprising St Barbe Art Gallery in Lymington to celebrate his centenary — and the unsealing of the testament — with an exhibition of 60 works. A republished edition of The Dark Monarch, complete with key, is on sale in the gallery shop.

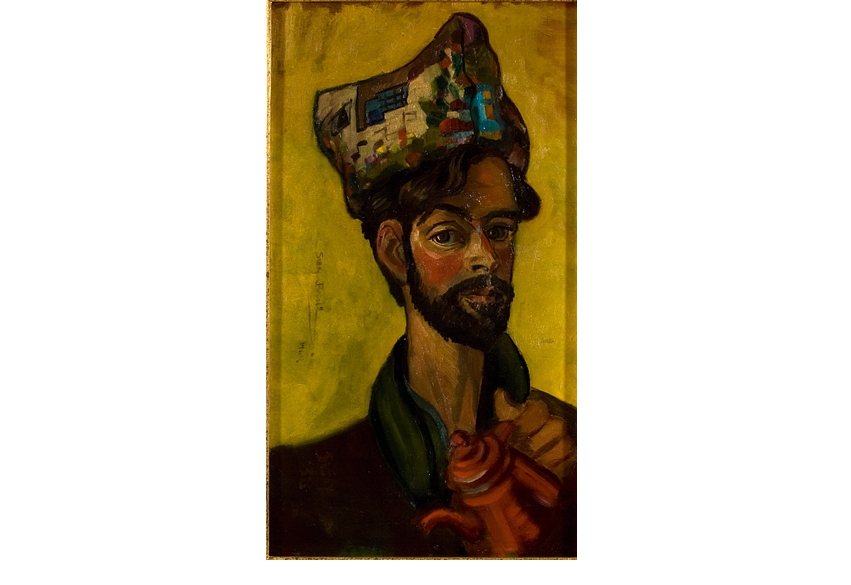

Three ages of Sven Berlin are represented in three self-portraits hanging at the exhibition entrance. ‘Shah of Persia’ (1938) shows the penniless young artist defying the Cornish cold with a patchwork tea cosy on his head and an empty teapot in his hand. ‘Self-portrait in a Shadow’ (1955) gives us the New Forest artist with brush and palette in his makeshift ‘paint shop’, slatted sunlight falling across the burgundy dressing-gown given him by his neighbour Augustus John. ‘Self-portrait: Enough – Too much!’ (1995) portrays the octogenarian artist with bright white beard, blue cap, scarlet waistcoat and harlequin scarf against an orange background; the quote from Blake’s Proverbs of Hell he is inscribing on a canvas refers to his arthritis but could equally refer to his palette. In mid-career Berlin adopted the Matthew Smith recipe of juicy paint and rich complementaries, but unlike Smith he was not a colourist. What he was — again unlike Smith — was a fabulous draughtsman.

The show includes several wonderful pen-and-wash drawings, some of the best dating from the war. A self-portrait sketch of 1944 made during the Battle of Verlo records the artist’s sunken features on the eve of the breakdown that saw him invalided out with shellshock. A subsequent drawing in livid washes of puce and olive evokes the queasy interior of the ‘Hospital Train’ (1945) en route to the military hospital in the Midlands where ‘like fallen statues from a lost civilisation we were repaired and set on our feet again’.

The fallen statue metaphor is apposite, for as this Bomberg-like drawing reveals, Berlin sees in 3D. Even when dashing off an impromptu watercolour portrait such as ‘Gypsy Mother & Child’ (1956) he communicates a sense of mass, and his pencil drawing of daughter ‘Janet (Greta) Berlin’ (1961) combines Matisse’s linear panache with Augustus John’s genius for portraiture, as a photograph in the catalogue proves. The best painting in the show is also a portrait, this time of stepson Will Fisher (1960) as a sulky teenager against a patterned backdrop reminiscent of the Omega Workshop. It’s Bloomsbury with balls.

Berlin thought real artists worked in three dimensions — ‘the others live a Picasso-faced existence with a flatfish vision’— but I preferred his monotype of a ‘Plaice’ (1948) to most of the sculptures in the exhibition. Although the marble ‘Sleeping Man’ (1949) can hold his own in the company of Epstein and Gaudier, I sympathised with the Penwith’s rejection of ‘Mermaid & Angel’ (1948), a maudlin riff on Rodin with a giant Epstein foot.

Berlin’s pen was mightier than his chisel. His friend Robert Graves’s comment on The Dark Monarch, that too much of its heat and power ‘goes roaring up the chimney, instead of heating the room’, could also be applied to his oil painting, but his marvellously vivid drawings are still warm.

Comments