It doesn’t matter which dictionary you consult, they all agree on what a song is: words, set to music, that are sung. Yet it’s also an entirely inadequate description, since there are so many types of song.

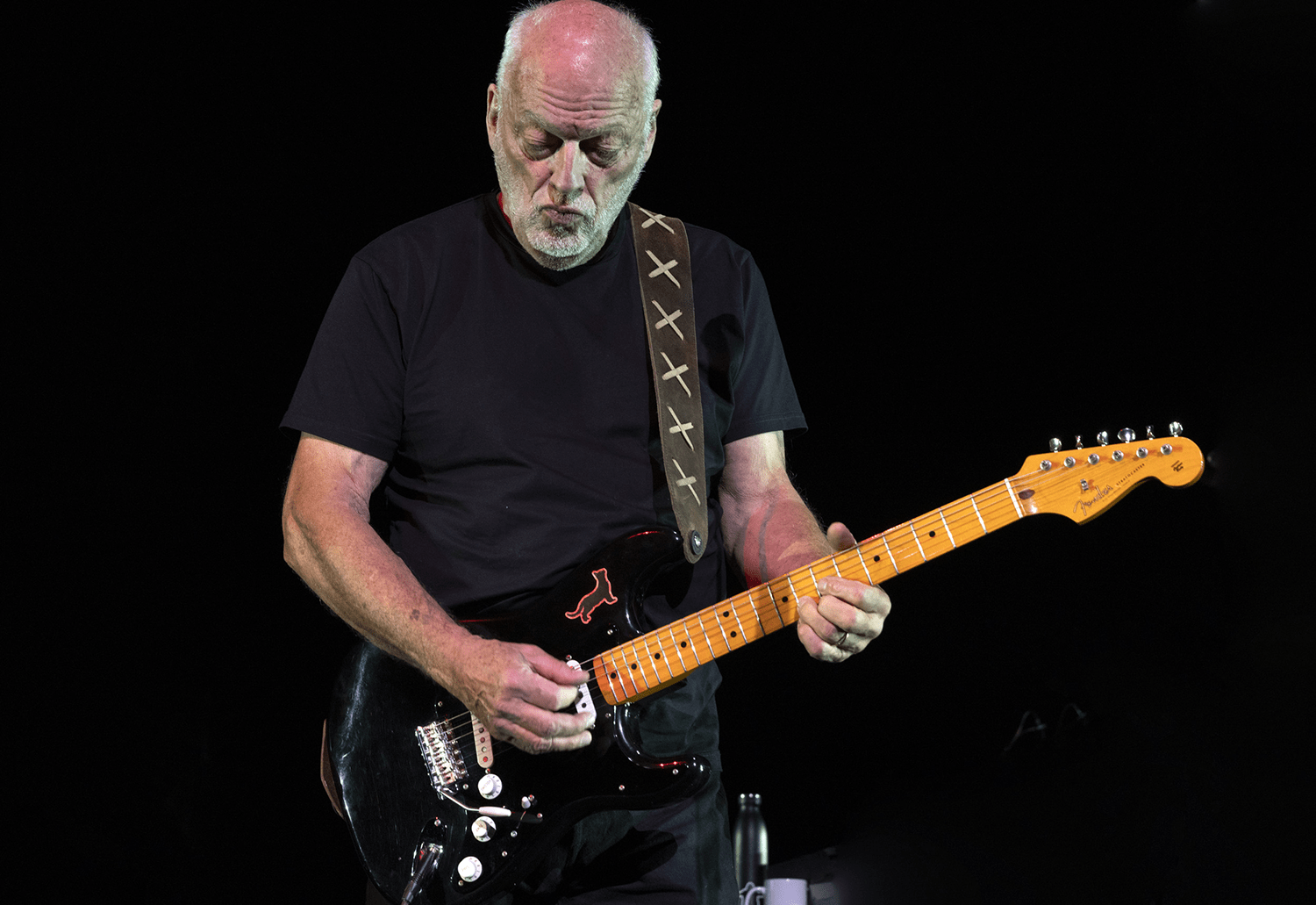

Take David Gilmour and Neil Finn, both men of passing years who like to switch between electric and acoustic guitars, both backed by plenty of singers and kindred instrumentation (though Finn didn’t have a pair of harps on stage with Crowded House), both playing music largely rooted in the late 1960s, both offering lightly mind-bending songs.

Yet this misses something crucial. Because, of the 23 songs that Gilmour performed – from both his solo and the Pink Floyd catalogue – over the course of two and a half hours at the Albert Hall, it became striking how few of them were actually songs. That’s not meant pejoratively. Gilmour simply does not do – and never has done – toe-tapping singalongs. We can test this theory out; just imagine a Pink Floyd song before you read the next paragraph.

There’s a fighting chance that what you imagined was something played at a torpid pace, with huge washes of keyboard, some possibly profound, possibly ridiculous lyrics and a soaring guitar solo. Something like ‘Shine On You Crazy Diamond’, or ‘Breathe’. That’s the template, and that’s what we got a lot of. And let’s face it, they’re not songs so much as chord progressions with lyrics and a guitar solo. (There’s no middle eight, or bridge, or chorus.)

That is a style that Gilmour and his bandmates invented, and it’s one, in its non-specific melancholy, that continues to echo down the decades. It’s what Brothers in Arms by Dire Straits was 40 years ago; it’s what Coldplay were updating when they became huge 20 years ago. And Gilmour, with that utterly inimitable tone – as unhurried as a bowler adjusting his field as the last session of a county championship game peters out into a draw – is its master.

There’s been a lot of critical love for these shows, and they are wonderful, but in their way they are every bit as unyielding as any monostylistic band. I wonder if some of the adulation comes, perhaps, from the likelihood of this being Gilmour’s last tour (he’s 78). And I wonder, too, if his former bandmate Roger Waters’s impressive campaign to make himself the most dislikeable man in pop has, in effect, made Gilmour the only game in town for critics who like ‘Comfortably Numb’.

That song, which closed the set, was a reminder of the effect of real songwriting. There’s a reason it was last. Here were verses and choruses rather than chord progressions – lyrics with such specific imagery that it’s hard to imagine the song not enduring – and, of course, two of the most famous guitar solos in history. Which is why everyone was there. To hear that sound. That tone.

Neil Finn can do sound and tone. But he does melodies above all: glorious melodies that seem to tumble out of him at will. He’s got so many that Crowded House could open with one of their biggest hits, ‘Weather With You’, rather than save it till the encore. This show wasn’t quite the ecstatic kaleidoscope that their gig at Shepherd’s Bush Empire had been earlier this year, but it was hard to find fault with it.

Even the less demonstrative songs from the new album Gravity Stairs – ‘Teenage Summer’, ‘Magic Piano’, ‘Oh Hi’ – shone because of the attention to detail. Here was sound and tone: interlocking harmonies, the shimmering guitar lines of both Finn and his son Liam (his other son, Elroy, played the drums), the careful addition of other instrumentation, including bouzouki (played by a fella from the Greek island where Finn now lives, apparently).

And that’s before you get to the catalogue. Finn is undervalued I feel. There are so many wonderful songs, all of which were written with both a keen appreciation of pop classicism and how to reach a wide audience. ‘World Where You Live’, for example, was recorded as bouncy 1990s pop and became a hit, but it could equally be played as a 1960s garage R&B rave-up, and virtually all of his songs sound as though they could withstand any arrangement.

‘Don’t Dream It’s Over’, ‘Four Seasons in One Day’, ‘Fall at Your Feet’, ‘Locked Out’ and – my favourite – ‘Distant Sun’ were perfect distillations of a vision of pop that seems incredibly human, gentle and intimate. What constitutes beauty in pop is very much in the eye of the beholder, but for me this show was truly beautiful.

Comments