Beijing, China

Beijing, China

When Boris Johnson became the London Mayor earlier this year, he was promptly informed that his first major duty would be to receive the Olympic flag on behalf of the next host city, in Beijing in August. “Sorry but that is one thing I cannot do” he is reported to have replied. “In August I will be on holiday with my family in Tuscany as always and there is no way I am going to Beijing.”

Come August and Bo-Jo did not just participate in the Olympic handover from Beijing to London, during the closing ceremony of the 2008 Games in the Bird’s Nest stadium, he stole the show with his “Ping-pong is coming home” speech at the post-event reception with Gordon Brown and Sebastian Coe, held at the temporary London House, near the Forbidden City in the centre of the Chinese capital.

It was a small presence by the forthcoming hosts in the city staging this year’s Olympics. Like never before at any other Games in recent memory, the organisers of the next Olympics in four years’ time have been barely visible during the last fortnight and a half of sporting competition. And that is just the way that the Chinese authorities wanted it.

They would not countenance any distractions from Beijing’s big moment, which led them to request of British officials that the promotion of the London Games should wait until after China’s Olympics are over. It was not a request that was expected to be refused. So, much to the frustration of Visit London’s tourism publicists – and their colleagues in other, related British organizations – the 2012 event remained in the shadows almost right up to the handover.

There has been none of the usual build-up at this year’s Games to the next one. No significant public happenings in Beijing to raise awareness of London as the coming host. No 2012 flags and banners, no logos on t-shirts or badges. With so few British tourists coming to China’s main city, most locals do not even seem to know where Britain or London are, with the only cue they recognise appearing to be any mention of Chelsea (the football club, that is).

The prevailing, subdued mood of the 2012 Games team was not helped by the very sad death, after a period of ill health, of the father of Lord Coe, the chairman of the organising committee of the London Olympics, whose arrival in Beijing was delayed as a result. Nor, probably, was the change of mayoral administrations in London this year a help, though the greatest thanks must be paid to the British capital’s voters that it was Boris and not Ken Livingstone who came to represent them in China.

Boris was immense in Beijing. He dwarfed Brown in every way, to the point that the Prime Minister almost seemed to be absent. Of course, Brown hadn’t actually been there for the opening ceremony. In hindsight, his decision not to attend was a pointless, futile, non-gesture. It was the start of the Olympic festivities which mattered to China, and which attracted to the Bird’s Nest a stunning array of world leaders, including George W. Bush, Vladimir Putin and even Nicolas Sarkozy, who had talked of not coming.

None of them returned to join Hu Jintao, the President of China, at the closing, but Brown was there for the handover to Britain. Yet his administration could hardly have read the clear signs from the Chinese leadership more wrongly. If there is one thing the 2008 Olympics showed, it is that such is the strength of the new China that it simply cannot be ignored or gestured at, but must be worked with, if it is to be influenced on vital issues like its human rights, Tibet, Burma, Darfur and Zimbabwe.

The relative importance to China of the Olympic opening and closing ceremonies was clear from how comparatively modest the spectacle was at the ending in contrast to the beginning. The opening had been watched by an incredible 842 million people on Chinese television, according to estimates, justifying all the effort put in to make the occasion unforgettable. The closing had the feeling of there being few ideas left over, with a touch of sadness at it all being over, amidst the joy of a successful staging of the Games.

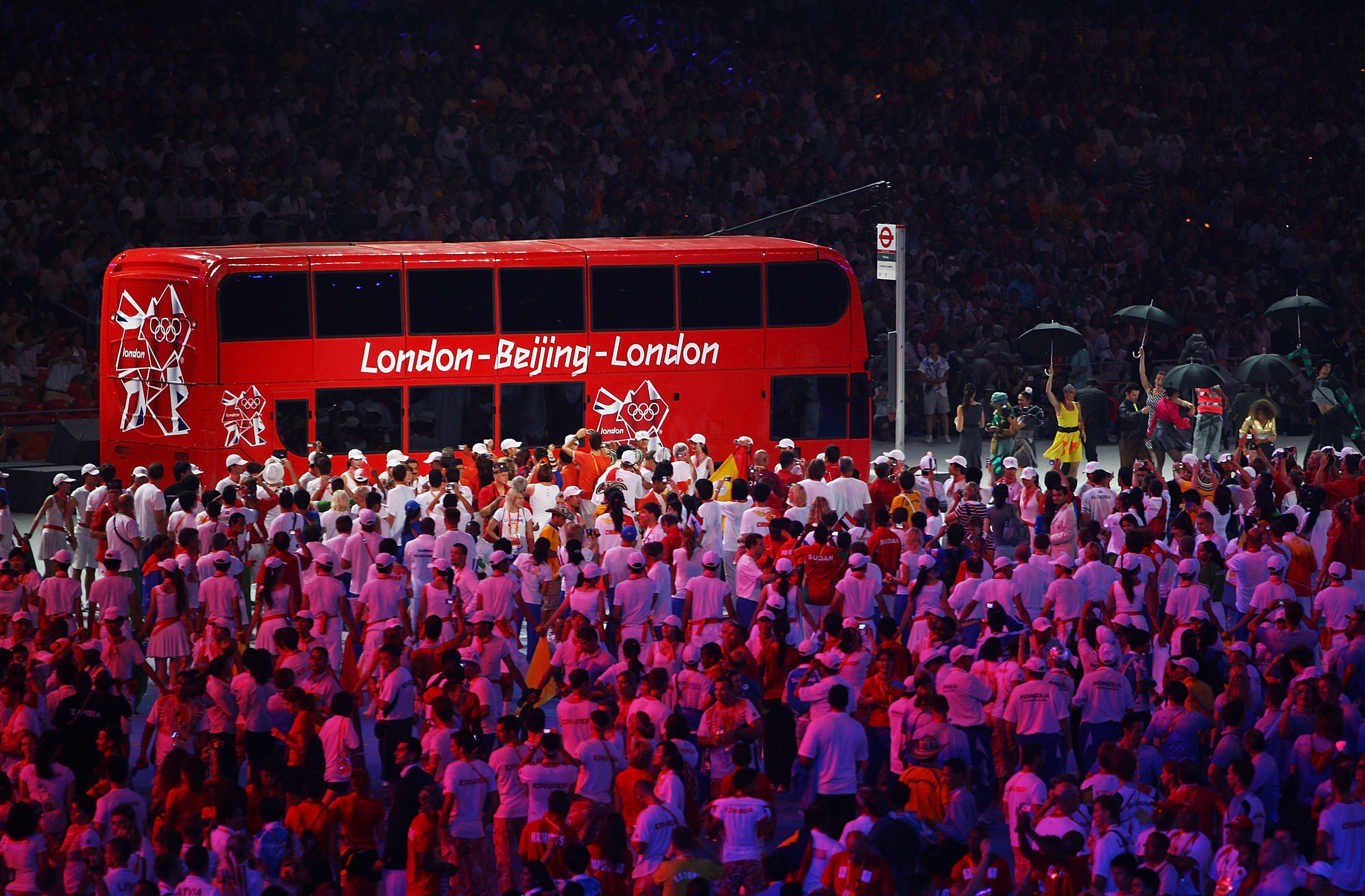

The best part of the ceremonial farewell to Beijing was the short London 2012 segment. David Beckham & Co. may have been a little bit embarrassing, but then these things almost always are. The red bus, zebra crossing street scene and unfurled umbrellas were fun. And it was actually very moving to see familiar images from home in an alien stadium far away, at an event shared by pretty much the whole world, with the thought that this great event is coming to our capital next.

It was just a shame that there were so many empty seats in the Bird’s Nest for the closing ceremony. A big factor seemed to be that, by the end of the Games, Beijing was already starting to get back to its old totalitarian, isolationist self in some ways. Strangely, many spectators were stopped from entering the Olympic Green area of the stadium in the north of the city, despite holding valid tickets, by ridiculously heavy-handed security personnel.

Nevertheless, Beijing’s Olympics have generally been seen as good ones – but so should they be for the £20 billion spent on them. But even if you have fine venues and the logistics run smoothly, you cannot buy good luck, so China was incredibly fortunate to have had Michael Phelps and Usain Bolt produce sporting performances that will be long remembered. Maybe there is something to be said for this number eight superstition, which led to the Games opening at 8pm on the eighth day of the eighth month of 2008.

Beijing impressed, but then it had to. While China wanted the rest of the world to see a modern nation rising, it was also selling the idea of itself as a great power on the international stage to its own people. It needed a successful Olympics from the dual perspectives of a well-received hosting of the event and domination of the sporting arenas, with the latter being attained as the Chinese team topped the medal table for the first time ever, with 51 golds to the USA’s 36.

Beijing had the equally significant task of winning over its own citizens, let alone the rest of China. For all the world and Olympic records achieved at the Games, perhaps the most interesting statistic was that the Chinese capital ranks only 14th among the nation’s cities for quality of life. Olympic workers and ordinary residents alike had been told to be positive about the Games, but there was a genuine excitement and pride at staging the Olympics, which will hopefully also be seen in London – budget disasters permitting.

Comments