Companies are facing critical shortages of staff. Commodity prices keep spiking upwards. Central banks are printing money on an unprecedented scale, and governments are running deficits of a size that haven’t been seen in peacetime before. What could possibly go wrong?

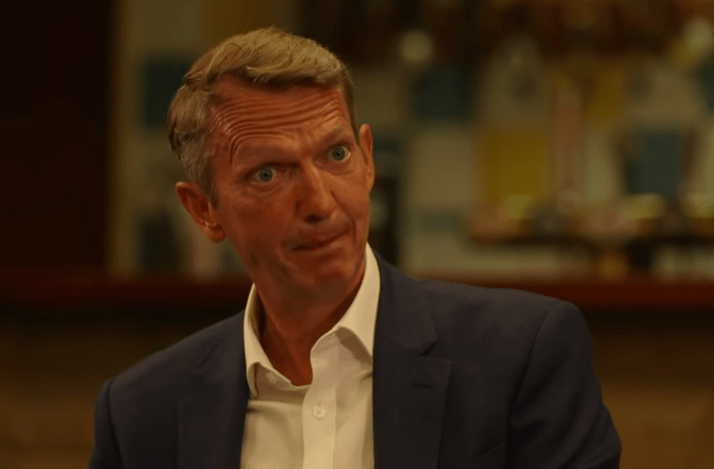

Well, quite a bit, as it happens. And the departing chief economist of the Bank of England Andy Haldane is completely right to warn that the real risk we face over the next couple of years is not a prolonged slump, but a re-run of the spiralling prices of the 1970s.

To his credit, Haldane was seldom afraid of challenging orthodox views during his time at the Bank. Now that he is leaving, he has become increasingly off-message.

‘The inflation tiger is never dead,’ Haldane warned

In an opinion piece for the New Statesman this week, Haldane sounded a cautious note about the likely consequences for the economy of the unprecedented rise in spending.

‘The inflation tiger is never dead,’ he warned. ‘While nothing is assured, acting early as inflation risks grow is the best way of heading off future threat. This is monetary policy 101. As the experience of the 1970s and 1980s taught us, an ounce of inflation prevention is worth a pound of cure.’

In fairness, Haldane sees some distinct differences between now and the inflationary 1970s. Central banks have a far more robust policy framework, and greater independence. Expectations are more firmly rooted. He could have added that trade unions across the developed world, are less powerful than they were. He might have said that the internet has made price comparison easier than ever, and that there are not any cartels, such as the once mighty OPEC, capable of doubling or tripling prices of key commodities overnight.

All those factors will make it harder for inflation to take off than it did fifty years ago.

But against that, there are two reasons why Haldane is right to be worried.

Firstly, the pandemic has shrunken supply right across the world, and even with vaccines will continue to do so, especially as fresh outbreaks crop up: the rise in infections in Taiwan could hit the supply of micro-chips, affecting supplies of anything electronic. And if it carries on spreading in Vietnam, there will be shortages of most manufactured goods.

More significantly, we have entered an ultra-Keynesian policy consensus, the like of which the world has not witnessed since the late 1960s. The United States government and leaders across most of Europe have decided they can tax and spend with impunity, that they can regulate without consequences, and they are smarter at investment and industrial strategy than the private sector.

Yet the evidence for that, to put it mildly, is weak. In truth, as he departs the Bank, Haldane’s successor needs to be worrying just as much about inflation as Haldane already does.

In his article, he quotes Hayek, inflation’s greatest intellectual foe last time around, approvingly. Let’s hope he leaves a copy of his collected works on his desk for whoever takes over the role: it will be needed.

Comments