What is a Bug? For this book, any animal that is not a Beast: the whole invertebrate realm, from the humble amoeba, through insects (more than half the book), to octopuses and sea-squirts (the distant forbears of you and me, lords and ladies of creation). Its scope, as with Flora Britannica and Birds Britiannica, is the parts that Bugs play in the human story: what they do to humannity with stings and jaws and injected saliva, what humanity does to them in the field and kitchen, their names (especially Gaelic), their roles in folklore, literature, art, music, films and photography. It is a book to enjoy at random, not to read from cover to cover.

There have been many books in this field. Amateur scientitsts, from bishops to the young Darwin, to a lunatic pseudo-Countess, used to give their lives’ leisure to finding and distinguishing hundreds of obscure Bugs. When I was little I loved C.M. Yonge’s The Sea Shore, twelfth in the New Naturalist series, and Ralph Buchsbaum’s Animals without Backbones. Like Marren and Mabey, these authors had a passion for the rare and bizarre, for horsehair-worms and chaetognaths and nemerteans and other phyla that the ordinary naturalist sees once in a lifetime, if at all. They revealed to me that this planet is inhabited by organisms that have their own agenda in life and work in ways utterly unlike the human species.

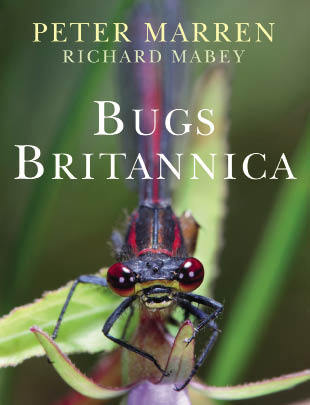

This delightful book revives that tradition. Technology has changed: universal colour printing has put magnificent photographs on nearly every page of the book. However, I miss Buchsbaum’s beautiful black-and-white drawings: a rotifer is not just an oddly coloured lump of protoplasm but a real creature, that lives and moves and has its being in three-dimensional ways that no photograph can convey.

Like Flora and Birds, this book comes of a research project on folklore. It includes ‘traditional’ folklore, a prime course being Dr Thomas Muffet, Shakespeare’s contemporary, spider-lover and possible step-father of Little Miss Muffet. It relates well-known (but true) stories like the Large Blue: a caterpillar that things it’s an ant, and the ants that think it’s an ant. It tells tales like the six million Cabbage-White butterflies said to have been caught (and eaten?) by sundew plants at Upton Broad, Norfolk. It tells of a mosquito peculiar to the London Underground. It presents especially the comtemporary folklore of oyster-eating competitions and pub signs and daddy-lonlegses said to crawl into sleepers’ mouths to poison them as they snore. Coverage is inevitably uneven: there is not much folklore about microscopic worms, a great deal about lice and bedbugs, some modern folklore about surgical leeches, but surprisingly little about ticks (were they once less common than now?).

I have a few regrets. Some Latin derivations are dubious. The authors feel obliged to produce an explanation every time a bug becomes commoner or rarer: Global Warming will do when all else fails. They might have mentioned how cockles and razor-shells created Holland by making the mighty wall of shell-sand dunes that fends off the North Sea. Anne Pratt, a century and a half ago, recommended Auricula (a kind of Alpine primrose) as a remedy for illness caused by inadvertently eating a Sea-Hare. I eagerly looked up Sea-Hares, a large and colourful marine slug, but could find no explanation of how people ate it inadvertently, though it is known as a quick aphrodisiac.

Bugs, like beasts and birds, have had their ups and downs. Collectors took their toll in the 19th century, when butterflies were worth money: some went further, to invent fake butterflies which long remained on the list of British species. A famous extinction was the Large Cooper, apparently a victim of thoughtless destruction of Whittlesey Mere in 1851; it was not exactly matched anywhere else in the world.

The greatest threat to bugs, among other creatures of this and other countries, comes from the human species’ fatal obsession with mixing up all the world’s animals and plants. No warning has been taken from the Woolly Aphid that halted cider-making, or the Phylloxera that very nearly put an end to wine (both from America). Maybe earthworms have had a (temporary?) reprieve from being eliminated by the great flatworm of New Zealand; but bees and honey may be doomed, and ladybirds will soon be no more, thanks to the Harlequin Ladybird from Asia. International trade has a lot to answer for.

Comments