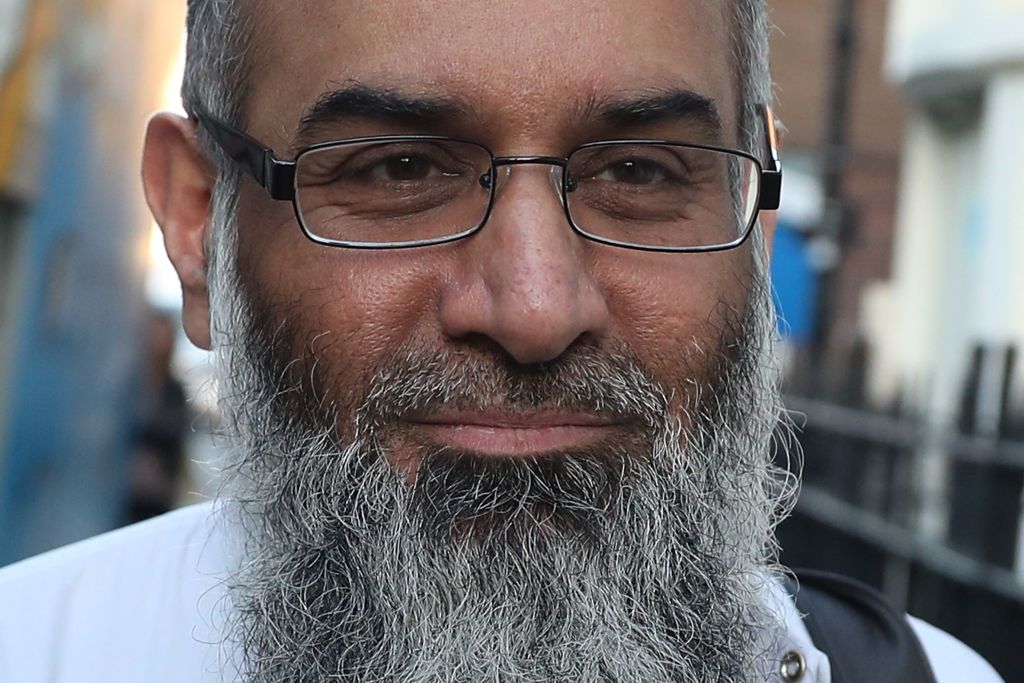

Anjem Choudary thrived on the oxygen of publicity and in the end could not stand being starved of it. He could have retired quietly after serving a five-year sentence for encouraging support for Isis, but as soon as his licence conditions expired, he was courting controversy again.

He put out press releases on WhatsApp and Telegram (largely ignored by the media), collected bans from online platforms, and began preaching over the internet to a group of five members of the Islamic Thinkers’ Society in New York. He did not know that two of them were undercover officers from the US. Much of what he said would not have been illegal in the US under their first amendment rights, but laws against encouraging violence are tougher in Britain.

Over the course of 30 years, Anjem Choudary had grabbed the headlines with stunts that included regular celebrations of 9/11, threats to picket soldiers’ funerals, burning poppies, and campaigns to ‘Stay Muslim, Don’t Vote.’ He displayed a picture of Buckingham Palace mocked up as a mosque and declared that he wanted to see the black flag of Islam flying over Downing Street and the White House.

There was one aspect of his past that Choudary never talked about – his own life of sin

His associates performed more controversial activities too, including the so-called ‘Muslim Patrols’ – intimidating non-believers in East London. A series of former members went on to launch terrorist attacks at Woolwich barracks in 2013, at Westminster and London Bridge in 2017, and at Fishmongers’ Hall in 2019. Others appeared in Syria, in Isis execution videos. In all Choudary’s associates were involved in at least 21 plots in the UK and abroad.

His lectures, recorded by the US undercover agents, revealed why that might be the case, including phrases such as: “Terrorism is part of the deen [faith]’ and ‘To terrorise the enemy, that it is a duty.’

Al-Muhajiroun, Choudary’s group, had always aimed to stir up as much controversy as it could muster with the approach that there was no such thing as bad publicity. Choudary acted as an apologist for al-Qaeda and Isis in international television interviews – refusing to condemn them, giving lengthy explanations of their motivations and warning of further attacks.

He described plotters as ‘decent young men’ and killers as ‘pleasant and quiet’. Even at his trial he described Isis executioner Siddhartha Dhar as ‘a bookworm.’ Over the years, al-Muhajiroun attracted the opprobrium of as many Muslims as non-Muslims with an uncompromising interpretation of their religion that declared believers as apostates just for taking part in civic life in Britain.

However, Choudary’s image as a firebrand ‘hate preacher’ belied a risk-averse approach to life that left him desperate to avoid going to prison. In Ilford, East London, he shared a terraced house with his wife Rubina Akhtar – also an Islamist preacher – and his children, including a son who worked for the Department of Work and Pensions. Around the corner lived his ailing mother, and Choudary tried to use his role as her carer to avoid being kept in jail while on remand.

Rather than joining Isis, Choudary hung back from endorsing the group in 2014 until he was put under pressure by other members, and then claimed he could not travel to Syria because it would ‘leave a vacuum’ in Britain. While a string of associates travelled, or attempted to travel, to join the Islamists, Choudary, a trained lawyer, stayed at home.

Choudary represented the second generation of extremist preachers, following on from Abu Qatada, the London-based preacher linked to Osama bin Laden, Abu Hamza, the hook-handed preacher from Finsbury Park, and Omar Bakri Muhammad, the so-called Tottenham Ayatollah, who was Choudary’s mentor.

Al-Muhajiroun operated as a co-operative of self-taught preachers, complete with sub committees, who fed off the lectures of Bakri, even after he escaped Britain for Lebanon in the wake of the 7/7 bombings. Choudary acted as the leader and spokesman for a series of successor groups – most notoriously Islam4UK – and performed a balancing act to keep the other activists happy.

However, it was his desire to recruit a new generation that caused investigators most concern, and in the end that led to him facing jail for a second, and almost certainly final, time.

There was one aspect of Choudary’s past he never talked about – his own life of sin as a law student in Southampton, calling himself ‘Andy’, when he consumed pornography, smoked drugs, drank alcohol and indulged in casual sex. These are the very practices that Choudary urged his followers to campaign against as they ‘command the good and forbid the evil’, an obligation he considered the ‘sixth pillar’ of Islam – which usually has five.

In the early 1990s, he returned from university to Woolwich, where he had grown up as the son of a market stall holder, and where he stood trial over the last month. There he re-engaged with his family and his father approached Bakri, who was visiting his local mosque, and asked him to teach his son. Until then, Choudary seemed set to take up a job as a solicitor with the Commission for Racial Equality.

It was to be a fateful meeting, not just for Choudary but for the dozens of young men he persuaded to follow the same path. Sentencing him to life in jail with a minimum of 28 years this week, Mr Justice Wall said Choudary had been ‘front and centre’ in an organisation designed to encourage and support acts of terrorism and that he ‘sought to groom young people.’

‘Organisations such as yours normalise violence in pursuit of an ideological cause,’ the judge added. ‘Their existence gives individuals the courage to commit acts which otherwise they might not do. They drive wedges between people who otherwise could and would live together in peaceful co-existence.’

Choudary is one of more than a dozen al-Muhajiroun preachers to find themselves behind bars as part of a ten-year campaign to disrupt the group. MI5, Scotland Yard, NYPD and many others will be hoping he is the last.

Comments