William T. Vollmann ruined my Christmas. But he also made my year. Like a fisherman scared by reports of mysterious beasts and monsters — Here be dragons! Gryphon! Basilisk! Unicorn! Serpent! — I’d been put off for a long time by Vollmann’s reputation as the great white whale of American fiction, the New Maximalists’ Maximalist, a kind of vaster, stodgier, blubberier David Foster Wallace. And Vollmann’s much discussed obsessions with prostitution, destitution, degradation — exhaustingly detailed in his many and often mega-books, from You Bright and Risen Angels (1987) right through to the seven-volume Rising Up and Rising Down: Some Thoughts on Violence, Freedom, and Urgent Means (2003) — are not my own. Frankly, I like nice. And at Christmas, traditionally, I like to read P. G. Wodehouse.

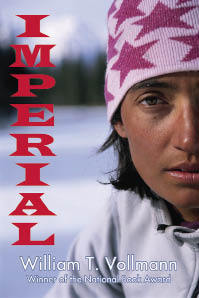

But, just when you think you know what you like, along comes a 1,300 page history of the US-Mexican border in Imperial County, California, that challenges your preconceptions and makes you lay aside The Code of the Woosters and postpone the turkey. Imperial consists of a couple of hundred rambling — some might say incoherent — chapters, mostly about the low lives of illegal immigrants, and the high politics of water supply, plus maps, a chronology, and a proper old-fashioned bibliography. There is also, apparently, an accompanying book of photographs, but this was not sent for review, and anyway Christmas pudding could not wait; there is a limit for even the doughtiest of reviewers.

Vollmann is lauded in America: over here, he’s almost unknown, for all of the usual reasons. There’s often a hyper-active, rosy-cheeked, super-tanned, long-limbed spoilt-childishness to much American writing, whether it’s Walt Whitman, or John Ashbery, or Thomas Pynchon, which can make us mannered, teensy Europeans just a little bit uncomfortable and suspicious. What is their problem? Why do they go on so? It should be admitted that the worst American writing can indeed resemble the nattering and smudges of a child savant, but the best is, well, it’s imperial. It’s not scrawl, it’s Big Writing.

And Vollmann is among the biggest of the Big Writers. He’s a lunk. He mentions Tolstoy as an influence; one thinks more readily perhaps of Jack London, met with Walter Benjamin. Productivity plus profundity. Vollmann doesn’t write books so much as produce think-pieces. His work forms not an oeuvre, but an archive, each book a massive end-of-term report on The World As I See It. In An Afghanistan Picture Show (1992) he produced his report on Afghanistan. In The Royal Family (2000) he did prostitution. Now, in Imperial, compiled over ten years, he recounts his adventures in the poorest county in California, among the Mexican crack addicts and the Border Patrol guards, in hidden tunnels and in factories, and in whatever repository or depository it is where a man can find turn-of-the- century copies of The Calexico Chronicle and the California Farmer.

You don’t have to be a psychoanalyst — although it might help, and you’d get paid — to intuit that this manic collecting and arranging of material is a struggle against death and dispersion. ‘I, who don’t belong here, was never anything but a word-haunted ghost’, writes Vollmann. In a recent interview in the New York Times, he spoke about the death of his sister by drowning — she was 6, he was 9, and he was supposed to be looking after her. ‘I’ve always felt guilty’.

I feel guilty. Perhaps it’s because it was Christmas, but I’ll be honest, some parts of the book I skimmed. It’s difficult to imagine a reader who wouldn’t. One becomes lost in the masses of stuff — like wandering around in the fog at the beginning of Bleak House, or on a tour of Xanadu. There’s a point at which information becomes an impediment, where abundance becomes a burden. That point occurred for me on p. 730, chapter 134, ‘We Now Worry About the Sale of the Fruit Cocktail in Europe’. I was beginning to worry about lunch.

Discouraged, disorientated, hungry — then you stumble across a passage like this:

Imperial is ink on decorated paper. Imperial is the poetry anthology Waka Roei Shu, inscribed by Asuka Mosaki (1611-79). Imperial is, in short, a scroll of a fabulous landscape, gold on white: gold palmlike trees, gold rice dikes which might as well be lettuce fields, gold clouds. Imperial’s wide landscape unrolls in either direction, potentially forever, dusty and hazy and sunny.

Vollmann has produced an account of a hazy, sunny, dying empire. Maybe Wodehouse isn’t so very far away.

Comments