In a ‘Dear Bill’ letter in Private Eye, an imaginary Denis Thatcher wrote off the BBC as a nest of ‘pinkoes and traitors’. That drollery points to the corporation’s paradoxical place in British life: an essential part of the establishment (‘Auntie’) yet sometimes its most daring critic, willing to put impartiality above patriotism. Jean Seaton makes one wonder at this impressive balancing act in a book that continues Asa Briggs’s magisterial history of the BBC up to 1987.

After the war many from newly liberated Europe thanked the BBC Overseas Service for keeping hope alive during the Occupation; this was reprised after the Berlin wall fell. Yet one British government after another from 1974 to 1987 attacked the BBC and the licensing system that guarantees its independence. A saga of excellence under siege.

Suspicion and threats came from both main parties. After plotting to abolish the licence fee, Harold Wilson moved the Beeb from the Post Office to the Home Office to keep it on a shorter leash. From 1976 — despite Cold War exigencies — Labour made the World Service renegotiate its funding year by debilitating year.

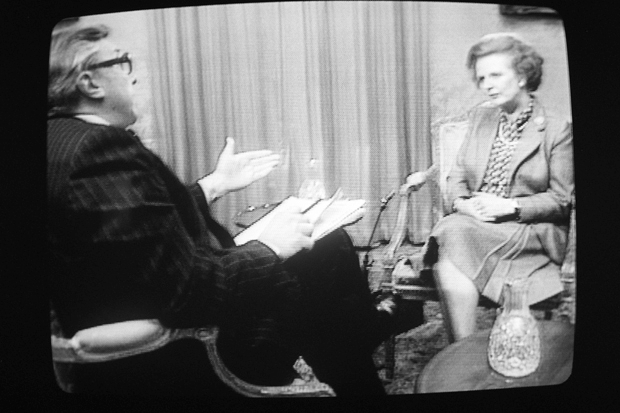

The Tories were even worse. Margaret Thatcher treated the BBC as yet another ‘enemy vested interest’, not wholly unlike the miners. Newscasters during the Falklands war spoke of ‘British’, rather than ‘our’ troops: well-established usage agreed during the second world war. But Thatcher ignorantly misread this as ‘rank treachery’. She threatened to replace the licensing fee with advertising revenue, turned down 27 invitations to appear on the Today programme, and sought Rupert Murdoch’s approval for her suggested new BBC chairman.

The BBC produced each hour of television more cheaply than any other European broadcaster and was leaching staff whose training it had financed to ITV. Moreover in the same period it had to fight its destructive and arrogant unions, given to restrictive practices as surreal and self-serving as those that troubled Fleet Street. Its reward was to have the Thatcher government try to bring it to heel by annual and inadequate licence-fee settlements during a period of inflation.

Instead of proceeding chronologically Seaton offloads a series of elegant dissertations, each generous with information and thought, within which she charts the BBC’s many battles and champions its successes. This is rich and essential cultural history rather than a light read.

The chapter on Northern Ireland, ‘The Right Amount of Blood’, is nonetheless gripping. The BBC was ferociously attacked by both sides in the conflict, as also by Westminster. Nationalists perceived it as an arm of the established order; unionists hated its refusal to act as their private stooge. A dozen car bombs were parked directly outside the Belfast BBC offices with another 143 in the vicinity. One brave cameraman suffered petrol bombs, paving stones and nail bombs; he was also clubbed over the head with a concrete sock and twice hospitalised. The BBC’s intrepid reporting of the use of force during interrogations was later shown to be accurate. Thus, by dint of establishing ‘a shared set of facts’ and through patient objectivity, it slowly helped enfranchise all sides, transmuting violent opposition into politics.

Light entertainment is not ignored. One American asked: ‘Gee — does that mean you have Heavy Entertainment there too?’ It is surprising to learn that only 12 episodes of Fawlty Towers and 45 of Monty Python were broadcast. There is an ecstatic hymn of praise to the pioneering educational virtues of Life on Earth and its heroic mastermind, David Attenborough. Other chapters evoke the rise of women within the corporation; the great age of TV drama, the Ethiopian famine, and the emotional feast provided by the royal wedding.

Many dream of the Queen: the BBC helped Princess Diana ‘enter the nation’s sleep’ too. Diana wept at the wedding rehearsal but the BBC kept this last-minute distress secret, ensuring that the pictures never reached newsroom or press. Later, Diana’s interview with Martin Bashir permitted her to challenge the monarchy without the usual rules of balance or questioning.

That interview falls outside the period covered by this book, at a time when BBC chieftains were sometimes charged with excessive pay rises. Is Seaton too starry-eyed about such matters? Jimmy Savile’s long, squalid history reflects badly on an institution that shares many of the weaknesses of wider society. Seaton acknowledges as much.The world nonetheless envies us the BBC, which has longer-term purposes than any passing government, and attempts doggedly to put the beleaguered British people in charge of their own story. We sometimes take ‘Auntie’ for granted. This absorbing book explains why we might feel proud of it instead.

Comments