It was only eight lines into O Brother that I realised I was in the hands of a good writer. John Niven’s landline phone has rung. His partner hands it to him. ‘I take the phone from her as she watches me in the intense, quizzical way we monitor people who are about to receive Very Bad News.’ I can’t recall a writer noticing that before (I presume a few have), but we have noticed it ourselves. And the narrative masterstroke is that now the reader is looking at the page in an intense, quizzical way, for we want to know what the Very Bad News is.

The VBN is that Niven’s younger brother Gary is in a coma, following a suicide attempt. He had been going off the rails from a young age; now, near-destitute, all his utilities cut off and with no way that he can see to pay his debts, he attempts suicide – an act of self-harm with a blade. But he has a moment of clarity and dials 999, describing what has just happened, or nearly happened. The operator is sympathetic, professional: an ambulance (and a police car, because of the knife) arrive, and Gary goes off to hospital. John learns this from reading the transcripts of the call, which he has had to fight for, because what happened at the North Ayrshire hospital Gary was taken to is a tale of astonishing incompetence which the authorities are not anxious to disclose.

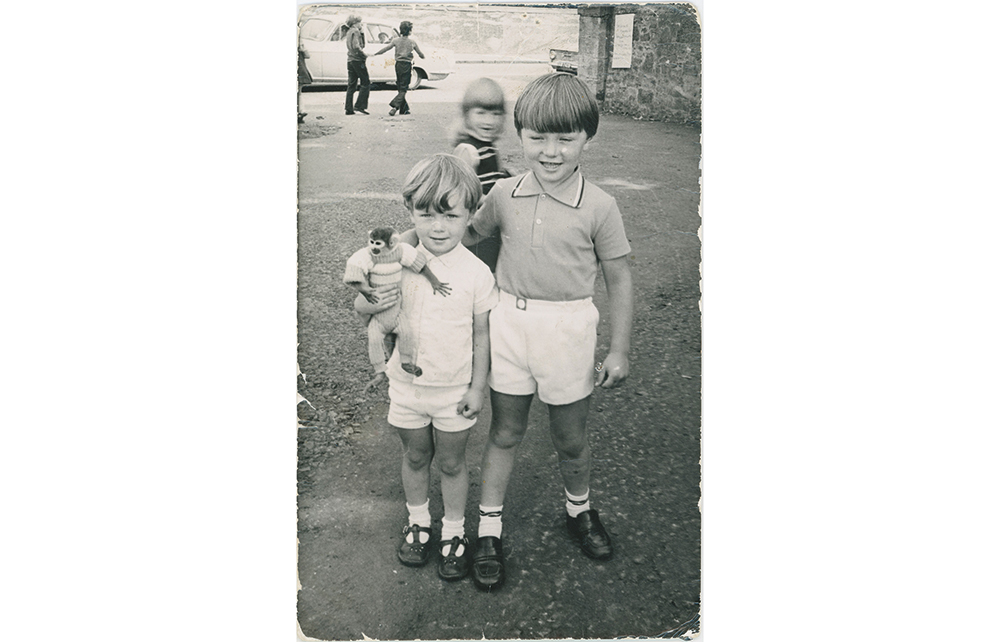

Gary, we learn very quickly, as did his parents, was an extremely difficult child

O Brother is an account of how Gary ended that way, but it is by no means the only story in the book. It’s also one of growing up in a working-class family in Irvine in the 1970s. The time, if not the place, will be deeply familiar to anyone born then, and there are quite a few of these memoirs about. Deborah Orr’s Motherwell sprang to mind most readily, as did Pete Paphides’s Broken Greek – both also excellent books – and when I read about certain kinds of furniture, makes of cars and television programmes (on just three channels, only one of which, ITV, is ever watched) a feeling of déja vu settles on me.

Here again are the parents mystified by the Beatles; the bookish child a freak, ostracised, mocked, or even thumped because of his or her love of reading. In this sense, Gary is very much more a product of his environment than his older brother; and Gary, we learn very quickly, as did his parents, is also an extremely difficult child. Add to this the regular thrashings his father deals out (ad hoc paternal corporal punishment being, as I suspect most people over 50 can attest, very much part of the picture in those days) and you have a recipe for final disaster.

Another part of the book also seemed very familiar – when John goes to London and becomes an A&R man for a record label. The job involves, among other things, finding new bands in the hope they will become the next big thing, and scenes revolve around astonishing amounts of alcohol, cocaine and anything else anyone can get their hands on. The excesses, recorded unflinchingly, reminded me strongly of a novel a friend gave me a few years ago, and the reason it rang such a bell was because – as I discovered after a couple of minutes’ research – Niven had written that too: it’s called Kill Your Friends, and it’s horrible and compelling in equal measure.

There is also humour in O Brother. Much has been made of this in the publicity surrounding Niven, although sometimes amid the sadness and casual violence this can be forgotten. But there is still a lot to laugh at, or with – usually involving the fraternal dynamic. There is the time John is caught masturbating in the toilet by Gary, the door unaccountably unlocked; or the elaborate backstory John concocts to convince Gary that he’s actually a Catholic.

The story of Gary’s descent is heartbreaking, and told with tenderness and honesty, the parts where Niven ventriloquises for his brother utterly convincing. The writing is first rate, without announcing how good it is. I can’t recommend it strongly enough.

Comments