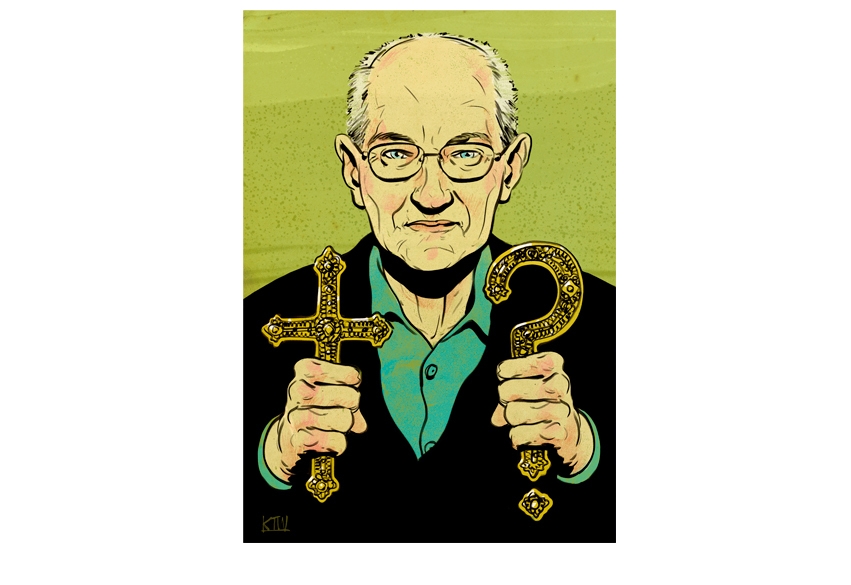

One staple of our national comedy is that someone must always fill the role of ‘Barmy Bishop’. While at Durham David Jenkins occupied the position, as perhaps in recent years has Rowan Williams. Certainly Richard Holloway recalls the morning while Bishop of Edinburgh when he woke to discover he had become the incumbent.

His liberal views on women priests and gay rights, as well as vocal doubts over the literal claims of Christianity (culminating in his 1999 book Godless Morality) caused derision in the press and eventually made his position as a Bishop and Primus of the Scottish Episcopal Church untenable. He stepped down in 2000 and now, approaching his eighties, has published an unsparing and moving memoir of his life to that date, Leaving Alexandria. So what is his faith now? I ask him over coffee in his Edinburgh home.

‘I’m dismissed as an atheist,’ he replies in his resonant, Scottish lilt. ‘I’m not an atheist. It’s too certain and clear a position. I would describe myself as in a permanent state of expectant agnosticism really.’

He mentions that he preached this past Sunday in Old Saint Paul’s, the church near Waverley Station where he spent some of the happiest years of his ministry. So what sermon did this expectant agnostic deliver? ‘I preached about how God hates religion.’

There remains a ‘bandwidth’ within which he feels able to preach. And though that bandwidth puts him at the farthest edge of conventional theology, it has in recent years brought him a far larger following of people from both in and outside religion.

The problem, he explains, is that religion ‘tends to scientise itself — to jump into truth claims’. In doing so it is doing exactly what a lot of atheist scientists do to the world. ‘They think they can package it.’ A product of the double-whammy of Darwin and historical criticism, he quotes Wittgenstein: to be religious ‘is to know that the facts of the world are not the end of the matter’.

This, though, was not the man that the young working-class boy from Alexandria, near Glasgow, had expected to become. As a boy Holloway resisted his father’s disapproval of the Church and was glad he did, for he was soon eyed for education in a monastic order in Nottinghamshire which rescued him from what might have been a bleaker life. He headed to Africa for missionary work, ‘filled with the romance of what I was doing’. But having fallen in love with the life of a saint, he found he could not become one, struggling to achieve the wholly ‘given-away life’ of which he longed to be capable.

Returning to Scotland as a young curate, he immersed himself in work among the Gorbals poor and submerged his theological uncertainties through the familiar route of attacking uncertainty in others. ‘It is the deepest irony of my life,’ he writes, ‘that I ended up the kind of bishop in my sixties I had despised when I was a priest in my thirties.’

He always understood the need for institutions, but tended to undermine them while he was in them. The ‘institutional loyalty gene’ was, he admits, absent and this, along with an inability to guard his tongue, caused considerable pain in others. He now says that had he recognised these traits sooner he would not have allowed himself to become a bishop. But after a period in America, at the very moment that his doubts were becoming strongest, that is what he became.

Did he ever think he was preaching lies? ‘No. I never preached lies. I never pretended to things I wasn’t feeling… It wasn’t about getting people to inhale certain historical facts. It was about somehow liberating them into a kind of redemptive, caring, compassionate way of living.’ But is it true? I ask him. Does he think the Christian story is true? There is a considered pause.

‘It’s true in the sense that myth is true, that Ovid’s Metamorphoses is true. I think they are ways of talking about the complexity of human experience, our need for redemption, for challenge, for forgiveness. I don’t think they are historically true. I don’t think he got out of the tomb.

‘If you turn Christianity into a kind of quasi-science about truth claims it becomes a kind of dishonest thing.’

He attributes some accusations hurled by atheists in recent years to just such a simplistic view, based on Sunday school stories and a failure to recognise how sophisticated priests and theologians can actually be. ‘The one true Christian doctrine is original sin,’ he says. ‘The fact that we are screwed-up creatures. We are neither completely animals nor are we completely mature minds — we are the strange dual creature which is why we are capable of terrible kindness and terrible evil. Christianity has wonderful ways of expressing that and tropes for discussing it and the need to redeem it. So yes, I think it’s true in that sense.’

But doesn’t it break down if it is metaphor? ‘It doesn’t have to break down’, he counters. ‘There are congregations that get it as a metaphor.’ In his memoir he writes that despite no longer believing in religion, he still ‘wants it around’. But how will that happen if even the clergy don’t believe in it as literal truth?

‘You put your finger on the pain here, because I know that, for people like me on the edge who want it around, it won’t be kept around by people like me.’ I suggest that this means it will fall into the hands of exactly those fanatical types who repelled him from the church at the infamous Lambeth conference of 1998. Won’t hard unthinking faith always overwhelm this more considered, beleaguered variety?

‘I think we are going to have to push through this,’ he replies. ‘I can’t predict what will happen. I just have a kind of a trust that a kind of charity and sanity will win through in the long run. But it will never conquer because this is always losing and winning and it is never absolutely won.’

•••

Speaking of which (and we are talking before the announcement he is stepping down) what of his successor as Barmy Bishop? ‘I love him. I think Rowan Williams is the best theologian Canterbury has had since Anselm.’ And he describes his sadness watching Williams’s ‘crucifixion’ in the worldwide institution he tried to head. Reflecting on the vast divide within today’s church, he says, ‘I think sometimes breaking is the best thing.’

This does not mean he is pessimistic about the future of the church — centralisation is a problem, and a split may do it good. As for society as a whole, though he acknowledges that there is plenty of ugliness in it, he also sees a lot of ‘graciousness’ and decency. And of course life is infinitely better than it was for many people, including for women and gay people.

Since the issue has come up, and since we are sitting in Scotland, I ask him about the Scottish cardinal who recently compared gay marriage to slavery. ‘Yes, I know. Keith Patrick, the wee soul,’ Holloway sighs. ‘He hasn’t been the same man since they gave him a big red hat.

‘And it’s unlike him because he’s a kindly man and it confirms one of my enduring problems with religion. There is something about religion… it can make kind people do unkind things.’ Holloway quietly carried out a number of gay marriages from as early as 1972 because ‘It seemed unmerciful not to.’ But he sees little likelihood of the Catholics following suit. ‘The interesting thing is, if the Pope decided tomorrow that gay people could be married or ord ained, Keith Patrick would do it. Which is a tell-tale recognition because it shows that for him it is not a profound issue of principle, it’s an issue of authority. I remember Tom Winning, the last Scottish cardinal, Archbishop of Glasgow, saying to me, “I’d ordain women tomorrow if the Pope told me.” So for them, obedience to authority is the greatest good.’

On the way back to Waverley station I pop across to his old church and linger awhile. ‘A muddled church for muddled people’ is Holloway’s fond description of Anglicanism. In the silence and darkness I find myself wondering again whether this Christianity, wounded but real, might still do for us.

Comments