With the passing of Cy Twombly — who has died of cancer aged 83 — a beacon light of rare civilisation has gone out in the Western world.

With the passing of Cy Twombly — who has died of cancer aged 83 — a beacon light of rare civilisation has gone out in the Western world. An elusive artist, with a highly developed faculty of challenge and response, he developed a pattern of investigation into the visual which was part philosophical inquiry and part sensual celebration.

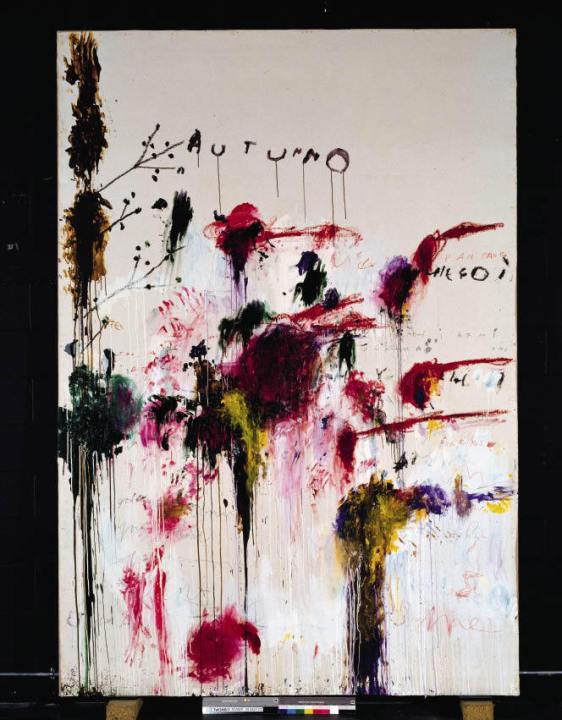

Despite close association with Robert Rauschenberg and Jasper Johns, recognition came late. He remained something of an outsider: an esoteric American artist who settled in Italy in 1957 and grew obsessed with Classical antiquity. He cultivated various literary muses — Catullus, Pound, Rilke, Pessoa, Virgil, Archilochus — and made gloriously expressive abstractions from their inspiration. Best known for employing calligraphy and script in his paintings, Twombly is no more ‘Cy the Scribbler’ than Pollock was ‘Jack the Dripper’, though the non-art press love nicknames to make them feel at home with anything that threatens to be profound.

Twombly called himself a Romantic symbolist showing things in flux. Other artists see him differently, as the following extracts demonstrate. The sculptor Nigel Hall (born 1943) finds landscape and music in Twombly’s work. ‘The paintings seem comparable to desert or arid wastelands which on first encounter appear unrewarding when contrasted with more lush or scenic landscapes. However, they reveal themselves slowly. What at first seems impoverished or ill-formed has by its very paucity an eloquence. The sculptures take a more concentrated form with the stillness and silence evocative of whitened ruins. They seem the visual equivalent to the spare and tentative explorations of Miles Davis’s music of the late 1950s and early ’60s. Like Davis, they evoke a feeling of melancholy and an awareness of the passage of time.’

Allen Jones (born 1937) recalls first seeing Twombly’s paintings when he started going to New York in the 1960s. In those days, Twombly was exhibiting with Leo Castelli, and Jones was interested to note how Twombly’s very individual work sat with a gallery of mostly Pop artists. It was clear to Jones that Twombly had carved out his own niche somewhere between the very different territories of Pop art and Abstract Expressionism, and that while he didn’t subscribe to Pop’s involvement with consumer culture he nevertheless imbued his own mark-making with meaning apart from its purely formal, abstract values. Thus when he used words on the surface of a painting, they were meant to be read as writing, not just as shape and gesture.

The first time I looked at any great concentration of Twombly’s work was in 1987 when a museum show that was travelling Europe reached the Whitechapel Gallery. I loved the dramatic freedom of it, the originality and mesmeric flow of mark, the occasional stutter and awkwardness disrupting what might otherwise have been too elegant in its assured occupancy of the picture space. But I also remember feeling slightly excluded when I heard Twombly eulogised as a ‘painters’ painter’. Now I think the ‘painters’ painter’ tag is too restrictive, and one of the things that’s so attractive about his work is its breadth of cultural reference. Gillian Ayres (born 1930), for instance, is drawn to Twombly’s Europeanness. As she says, it’s just that quality of culture that’s needed nowadays, and is so hard to find among the self-referential young. ‘I think he’s a sort of hero, unmistakeably, one of the things you really look up to — like Beckett as a writer.’

Ian Welsh (born 1944), a painter who seeks visual expression for scientific observation, feels strongly about the issue. He writes: ‘In an age when perhaps too much attention and respect is paid to the self-obsessed doodles of some contemporary artists and writers, it is with relief and anticipation that one returns to the work of Cy Twombly. He is an artist whose very personal language is used to construct works which are at one and the same time both timeless and intensely contemporary, mining as they do the creative energies and cultural offerings from all the known history of sophisticated man and responding to the immediacy of the modern environment. A profound joy!’ Welsh stresses that artists can make totally personal and individual work without indulging themselves in autobiographical maunderings; that in fact the business of trying to make direct and telling marks in painting demands an ability to distance oneself.

Veteran realist Anthony Eyton (born 1923) proves that Twombly’s appeal is not limited to abstractionists. ‘Like Turner, Cy Twombly was a visionary with a sense of the cosmos. They are both poets remembering a place or experience and recreating the memory later on. Both are fond of words: Turner with verses attached to his paintings, Twombly with words actually inscribed on the painting. Both had an enormous respect for the support, Turner in his watercolours especially, and Twombly in the light inherent in the paper or canvas so that white to him was a source of magic to be chastised or caressed. He was a master of spontaneity, letting himself go to roam free in associations in his imagination, free of the tyranny of visual fact. To this extent he was like a Zen poet.’

Lorcan O’Neill, a leading art dealer in Rome who first got to know Twombly when working for Anthony d’Offay in London, has this to say: ‘Cy Twombly is one of the truly great artists. He had a profound understanding of the human condition, and his spirit — of such intelligence, humour and delicacy — is visible in all his work. I was always aware of what a privilege it was to have been around him, he was like one of the giant granite columns in front of the Pantheon; ageless, strong and forever impressive. His courage and independence as an artist are a constant inspiration to many people.

‘His passing is a shock because you can never prepare for the void that, at whatever age, the departure of such a man leaves.’

Comments