The name is the only clue you need. The French and German words for ‘yes’ show that the board will always tell you what you want to hear. Mind you, Elijah Bond and Charles Kennard, who invented the Ouija board for their novelty games company, claimed that Bond’s sister-in-law, a spiritualist, was given the name by the board itself at a séance in 1890, and that it meant ‘good luck’. Clearly the person on the other side wasn’t much of a linguist.

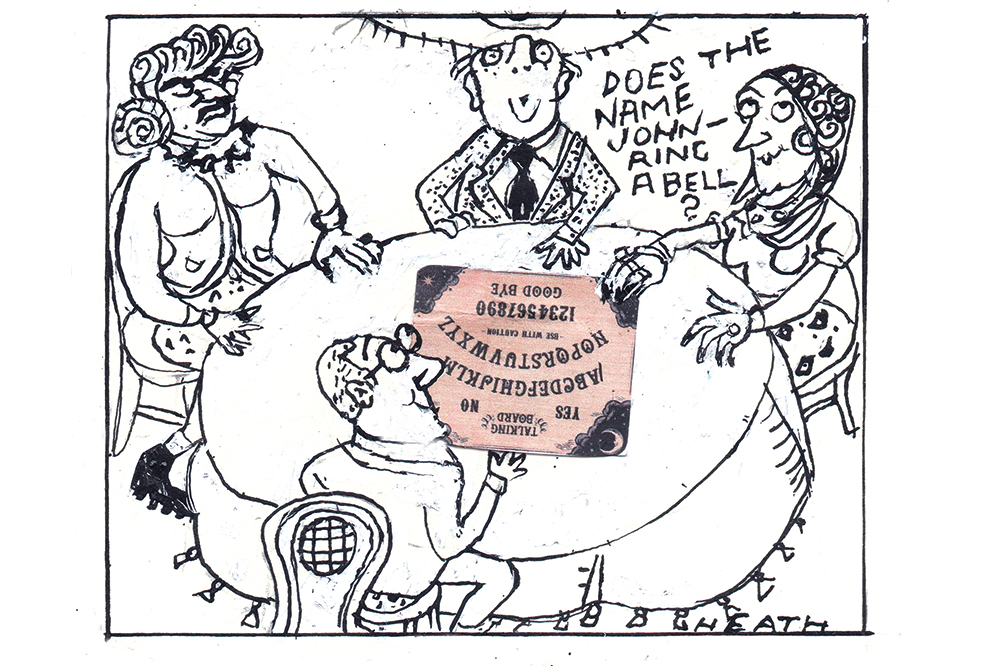

Another explanation comes from the US comedian Brett Erlich: ‘“Ouija” is short for “we just push this thing around and make it say what we want to”.’ That certainly fits with the science, which is something known as the ‘ideomotor effect’, where simply thinking of something can cause you to make physical movements, even though you’re unaware of the reason. The people with their hands on the pointer (or planchett – French for ‘little plank’) direct it around the board without realising what they’re doing.

The magicians Penn and Teller demonstrated this by blindfolding participants in an experiment, then changing the position of the board without telling them. The group proceeded to move the planchette into what had previously been the ‘yes’ and ‘no’ positions, but which were now blank spaces. Derren Brown debunked the Ouija board without even trying to. A friend brought one to his home, and insisted on contacting Brown’s late grandfather. The board spelled out ‘R-U-P-E-R-T’. Brown had to break the news that his grandfather’s name had been Fred.

But as ever, those who want to believe will believe. G.K. Chesterton used the board as a teenager, while Arthur Conan Doyle (famously a fan of spiritualism) tried to convince, of all people, Harry Houdini. Doyle’s wife, fancying herself as a medium, ‘contacted’ Houdini’s dead mother, who wished her son a happy Christmas. The magician observed that his mother had been Jewish, so the message was unlikely.

Then there are those who pretend to believe. This can be for publicity – according to Alice Cooper’s early press releases, a Ouija session had revealed that the singer (born Vincent Furnier) was the reincarnation of a 17th-century witch of that name. Cooper later admitted it was simply the first name he’d thought of. Or the pretence can be to conceal something. In 1978 Romano Prodi, then a minister in the Italian government, passed on a tip about the location of a kidnap victim being held by terrorists. The obvious conclusion was he had a source connected to the terrorists. Prodi himself insisted he’d got the information using a Ouija board.

How should you react if someone whips out a board for Halloween? You could get all hot and bothered, like the Christ Community Church in Alamogordo, New Mexico, whose congregation burned Ouija boards in 2001, calling them ‘symbols of witchcraft’. (The bonfire also included Harry Potter books.) Or you could just have a laugh, like the spokesman for Poundland when the store was criticised for selling a Halloween Ouija board in 2020: ‘We understand the spirits shook in disbelief when they were told it was only £1.’

Comments