The word ‘hoax’ did not catch on till the early 19th century. Before that one spoke of a hum, a frump, a prat or a bilk. But 18th-century Britain, even if not rife with talk of ‘hoaxes’, was full of incautious souls at risk of being bilked. James Graham, a Scottish quack, was able to charge infertile couples £50 a night to lounge in his Celestial Bed, which had a mattress lined with hair from stallions’ tails. The artist Ann Jemima Provis and her father, Thomas, caused embarrassment to the Royal Academy by conning its president, Benjamin West, into thinking they had stumbled on a rare manuscript that would allow him to emulate the luminous style of the Venetian masters. William Charlton painted black spots on the wings of a yellow butterfly and announced thathe had discovered a new species, which in due course found its way into the British Museum.

None of the above appear in Ian Keable’s The Century of Deception. But each is a symptom of an age when it became common to speak of ‘English credulity’. Regardless of whether the willingness to believe absurd fictions was a specifically English affliction (Keable thinks not), there was no shortage of hucksters eager to exploit it. The rise of newspapers and magazines meant that tales of the bizarre and the outrageous could circulate widely and quickly, while the rapid increase in printed advertising made it easy to promote stunts and shams.

It was claimed that a Formosan man, if sick of his wife’s disobedience, might eat her heart in front of her relatives

Keable, a professional magician, warmly appreciates the mechanics of deception. He regards a successful hoax as similar to a good illusion, since both involve ‘amicably spoofing people for the sheer joy of it’. Yet he admits that only one of the ten he recounts can truly be said to fit this definition, and most are malign or cynical. Among his chosen perpetrators is the less than amicable Chevalier de Moret, who lied about being a friend of the Montgolfier brothers in order to charge people to watch him fly in a balloon (which it turned out he couldn’t even inflate). Another is the fantasist William Henry Ireland, whose Shakespeare forgeries made a laughing stock of everyone who fell for them, above all his own father.

The most notorious of Keable’s choices is Mary Toft. In 1726 this healthy young hop-picker from Godalming tricked several prominent doctors into believing she’d been delivered of a fluffle of rabbits. Her motives were financial — she hoped to make a living by exhibiting herself at freak shows. But the fake birth came at a price; she described the sensation of it being like ‘very coarse brown paper… tearing from within her’.

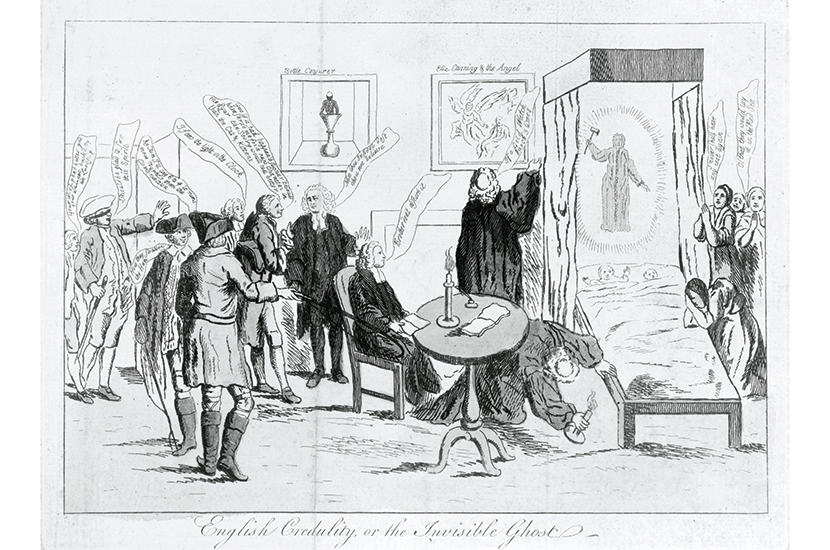

Keable also revisits the well-known story of the Cock Lane ghost, said to haunt a house near London’s Smithfield market in 1762. In truth, the haunting was a scam instigated by Richard Parsons, a toper badly short of funds, but reports of the ghost’s sinister scraping noises attracted the interest of Horace Walpole and the Duke of York. Eventually a local clergyman mustered a team to investigate. This included Samuel Johnson, who confirmed that the strange goings-on at Cock Lane had nothing to do with ‘agency of any higher cause’.

Johnson lumbers into view in another chapter, as a friend of George Psalmanazar, an energetic Frenchman who tried to pass himself off as the first native of Formosa to reach Europe. Convinced that Formosa was part of Japan, Psalmanazar ought to have been easy to expose. When asked to write a book about his homeland, he hit on the plan of ensuring it would ‘in most particulars clash with all the accounts other writers had given of it’. This succeeded, partly thanks to his flair for fabrication and partly because of his hosts’ ignorance. In the book’s second edition he made even more outré claims — for instance, that a Formosan man, if sick of his wife’s disobedience, might eat her heart in front of her relatives.

The other stories here feature Jonathan Swift at his most mischievous, a teenage Benjamin Franklin, the knife-wielding gypsy Mary Squires, and a wandering minstrel who rejected £100 for a one-off performance of unspecified ‘services’ at Windsor Castle. Narrating their escapades calls for fleet-footed verve, but Keable’s approach is workmanlike, never more so than when attempting a bit of showmanship: ‘Stand by not just to be educated but, more importantly, to be entertained’; ‘Welcome to a rollicking ride, accompanied by gasps and laughs’; ‘If you are expecting a neat tie-up at the end of this chapter, prepare to be disappointed.’ Still, he is scrupulous about weighing the evidence in each case he considers, and he leaves us with an unsettling observation: in the 18th century, at least, male hoaxers tended to be privileged and self-indulgent, whereas female ones were simply seeking to escape poverty.

Comments