The question of why things fall has puzzled our species since we crawled out from the darkness of our primitive ignorance. Aristotle was the first to offer a serious theory. He proposed that each of the four elements (earth, air, fire, water) had a natural place to which it innately wanted to return. Fire and air rise because their place is in the heavens, whereas earth and water return to the Earth.

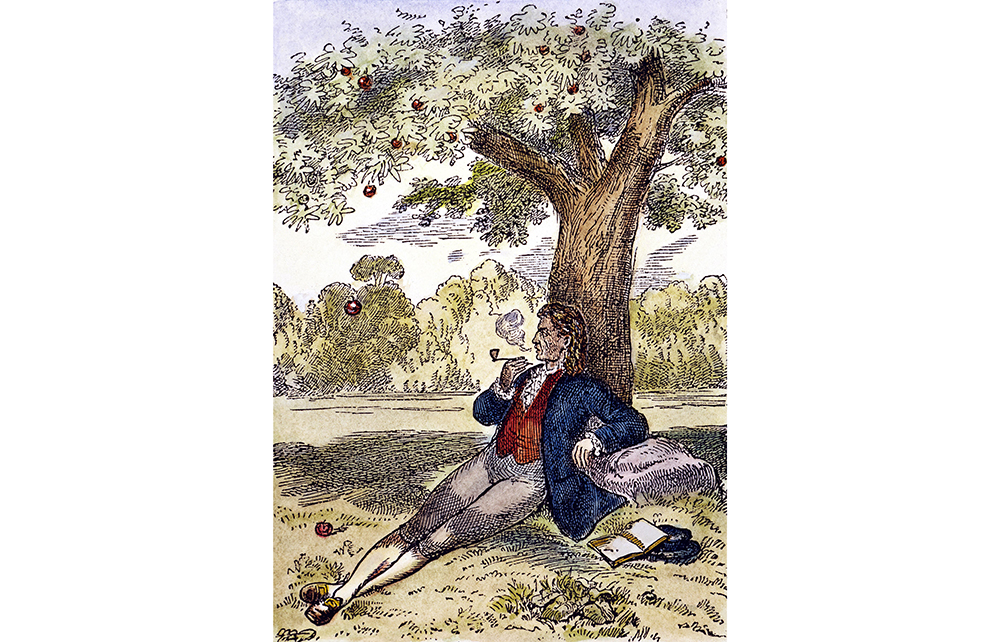

Aristotelian philosophy had such a profound impact on human thought that this view prevailed for nearly 2,000 years. Only with the Renaissance and the ideas of Kepler and Galileo was it finally challenged; and only by standing on the shoulders of these giants was Isaac Newton able to make probably the greatest intellectual leap ever. It is often assumed that with the publication of his Principia, the curtain was pulled back and the great mysteries of the universe were reduced to a trick. Gravity, and by extension the motion of everything in the universe, could be described by a simple equation.

But this is a mistake. What Newton did, rather, was emphasise a distinction first made by Descartes, namely between what we know and what we understand. That gravity should be ‘innate and act, seemingly without any mediation, over great distance within a vacuum’ was, to Newton, ‘so great an absurdity that I believe no man who has in philosophical matters a competent faculty of thinking can ever fall into it’.

These words of Newton end the introduction of the theoretical physicist Claudia de Rham’s The Beauty of Falling, which begins with a description of gravity as ‘such a familiar concept, present in every language and culture, yet one that scientists have struggled to understand for millenia’. This duality of familiarity and ignorance provides the essential texture of a book that aims to explain the universe’s ubiquitous and most mysterious force, ‘the reason why it can exist and evolve’. The instantaneous nature of Newton’s gravity was an early sign that it was not the final answer. But, de Rham asks, ‘are we any closer to understanding how gravity communicates?’

To answer this, she builds the foundations of our current knowledge with a brief study of gravity since Galileo. For anyone who has read pretty much any popular physics book, this is a familiar path. The prototype relativity of Galileo; the physics of Newton; the strange orbit of Mercury; the aether; the Michelson-Morley experiment; Einstein’s gravity; quantum mechanics; black holes; the breakdown of physics. All that really changes are the analogies and metaphors. For those new to the genre, this is still an entertaining sweep of the required reading and an excellent primer for more difficult concepts ahead.

We are also introduced to light’s cousin ‘glight’, or the name for the gravitational energy spectrum analogous to the electromagnetic one, suggesting there are ‘colours’ of gravity; and de Rham interweaves the modern experimental evidence for general relativity – gravitational waves, the expansion of the universe – with its theoretical origins neatly and colourfully. It is in this context that we meet ‘the main character’. One that went ‘unnoticed for billions of years… never changed, never evolved, never made a sound, at least not until everything else had faded away’.

Dark energy is the soul of modern physics. Along with dark matter (related only by their invisibility), it makes up 95 per cent of the universe, yet we can only observe it in the mathematical abstract or through its inter-action with visible matter, i.e. through gravity. And while its presence is predicted by general relativity, its existence is one half of the ‘greatest discrepancy in scientific history’. That is, between the incredibly precise yet mutually incompatible theories of general relativity and quantum physics. And gravity, it seems, lies somewhere in the middle. De Rham communicates the innate complexity of this schism deftly; and manages to convey her position as both expert and completely ignorant with an almost Socratic delight, before asking whether ‘the mysteries we are currently facing are a clue to a deeper truth?’

As the subtitle suggests, there is a secondary theme – ‘a life in pursuit of gravity’. It has seemingly become de rigueur in the modern age of identity that even science books should contain a personal narrative. It is not enough to read about the wonders of nature; we must also read about the journey of the author. At least with this book, you know that from the outset. It also helps that de Rham’s experiences are quite interesting and relevant. She made it down to the final 42 applicants for the European Space Agency’s astronaut programme in 1992 (rejected owing to a diagnosis of latent tuberculosis), and became a pilot and scuba diver, too.

But beyond these gravity-defying experiences, which cumulatively could take up about three pages, the writing descends into the banal depths of the familiar. De Rham even uses the mutual attraction and repulsion of two bodies in orbit as an analogy for the difficulty she and a fellow physicist had in being together in their early relationship. ‘Of course, if you ask me, I would say that what drew me to my partner Andrew…’ is not what I expected to read in a book about physics. I can’t remember reading, say, The Selfish Gene and thinking: ‘I wonder how Richard met his wife.’ But such is the fashion. If you like this sort of stuff, excellent; if you find it a touch narcissistic, skim.

In the final two chapters, de Rham gives us what we came for: new physics. Here she is at her most natural (coincidentally, there are almost no personal digressions). Received wisdom is difficult to overcome, even in physics, and we learn how she and her colleagues struggled against a deep-rooted general relativity ‘ideology’ to get a subversive theory of gravity published. Their findings have since been ‘recognised and ranked among the most influential discoveries in physics in the past decade’. Once you have read about ‘massive gravity’ (that gravity is actually composed of particles) and what its universal implications are, you will no doubt see the world anew. And marvel at the fact that we can know so much yet understand so little. Which is no doubt a good thing.

Comments