Too many books? Yes, we had too many books. That’s what our social worker told us when we were being assessed to see whether we were suitable parents to adopt a baby from China back in 1996. It seemed to us, a middle-class, well-educated couple, an extraordinary statement and so it appeared to our friends and acquaintances. But that was, and is still to some extent, the credo at work in assessing potential adoptive parents.

A significant number of social workers continue to believe that a child should be matched as closely as possible with the social class and ethnic background of the adoptive parents, even if that means children being held in institutional care far longer than is good for them. An adoption textbook, published in the 1970s but still being used in the late 1990s, has the following advice, which has endured: ‘Where the choice is between the foreman of a factory and the managing director, all other things being equal, we would favour the foreman as an adopter.’

We took the agency that turned us down to a tribunal and won the right to be assessed by a second one, which approved us. Three-and-a-half years after our first letter (what my husband called an ‘elephantine pregnancy’), we finally brought our daughter home.

The world has moved on since the 1990s. China closed its doors to overseas adoption last November after 32 years. This followed the abandonment of the one-child policy, introduced by Deng Xiaoping in 1979 to ease an exploding population, which resulted in tens of thousands of baby girls being left in fields, parks or outside orphanages.

China now has an ageing population, with more boys than girls. And China’s loss was the West’s gain. There’s now a diaspora of young ethnically Chinese people all over the United States, Europe and Britain, who were part of the estimated 160,000 or so babies adopted in western countries during that time.

The one-child policy was first eased in 2015, when the Chinese government decreed that couples could have two children, raising the number to three in 2021. Not that modern Chinese couples are enthusiastic about the prospect of bigger, more expensive families, but that’s another story.

The process of adopting babies and toddlers in this country is subject to damaging delays

Yet while China has stopped allowing overseas adoption, there are still many countries with children in need. The leading countries putting children up for adoption today are India, Colombia, Bulgaria, Haiti and Nigeria. Bizarrely, for those who think public policy should be consistent, social worker attitudes about interracial and inter-class adoption within the UK seem to go out of the window if people look for children overseas – although an assessment still must follow most of the guidelines applying to a UK adoption. It’s an anomaly that nobody seems able to explain.

Back in Britain, the number of babies available for adoption has dropped to the low hundreds. More single women now keep their children and bring them up alone. Any babies given up these days are, quite rightly, adopted by young couples, with 40 as the unofficial cut-off age for adoption of children under five.

But even the process of adopting babies and toddlers in this country is subject to damaging delays. One white couple who recently adopted a white baby girl told me she had been abandoned at birth but placed in a foster home and only approved for adoption a year later. These kinds of delays can be even longer where couples or single adopters want to adopt a British child of a different race, despite repeated attempts to speed up the process.

In theory, the Adoption and Children Act 2002 eased the strictures on interracial adoption. Its intention was that although a child’s racial and cultural origins were relevant factors, ‘a child’s ethnicity should not be a barrier to adoption’. But concerns persisted that racial differences were still preventing children of different backgrounds from being placed with families.

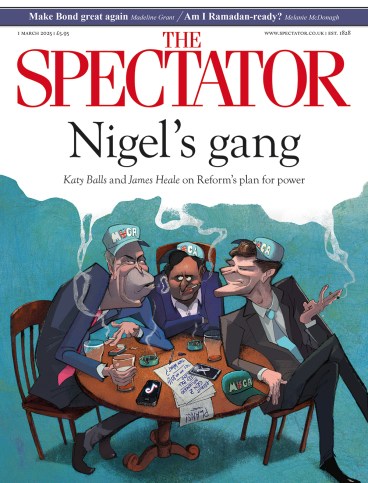

This issue was highlighted in 2012 by The Spectator’s editor Michael Gove when he was education secretary. ‘It is outrageous to deny a child the chance of adoption because of a misguided belief that race is more important than any other factor,’ he said. ‘And it is simply disgraceful that a black child is three times less likely to be adopted from care than a white child… I promise you I will not look away when the futures of black children in care continue to be damaged.’ In 2014 the Tory-Lib Dem coalition government confirmed that ‘a child’s ethnicity should not be a barrier to adoption’. Even so, some social workers appear to be fighting a rearguard action. They believe that the adoption of poor children by middle-class parents is ‘social engineering’, which they say contravenes the European Convention on Human Rights in relation to class discrimination and the right to a private and family life.

Such views still influence adoption decisions, whatever the government might decree. One white couple told me that their social workers would not match them with a black or mixed-race baby unless they could prove they had close African or Afro-Caribbean friends.

This might just be understandable if the number of children in care in Britain were not a dire problem. In March last year, 83,630 children were in local authority care, of which two-thirds were with foster carers. Only 2,980 children were adopted during the previous year, while 5,880 were awaiting adoption.

The problem is still particularly severe for non-white children. Although 29 per cent of children in care are from ethnic minorities, they make up only 16 per cent of adoptions. Perhaps the biggest scandal of all is the time between a child entering care and being placed with an adoptive family. Last year the average was 883 days – or more than two years and five months.

There is still much room for improvement. To help raise awareness of these issues, I have written a play drawing on our struggles as a middle-class couple looking to adopt a child. Called Too Many Books, it is a work of fiction, but it’s informed by our and others’ experiences in treading through the treacle that is the British adoption system.

Too Many Books is at the Upstairs at the Gatehouse theatre, Highgate, until 16 March.

Comments