Like most documentaries, Britain’s Nuclear Bomb: The Inside Story (BBC4, Wednesday) began by boasting about all the exclusives it would be serving up. Unlike most, it was as good as its word. What followed did indeed contain much previously unseen footage and interviews with people — including ‘this country’s bomb-maker in chief’ — who’ve never before spoken about the part they played in Britain becoming a nuclear power. It also did a neat job of fitting the story to our favoured national myth: the one about old-fashioned British pluck and know-how triumphing over both the odds and the shamefully professional ways of other countries.

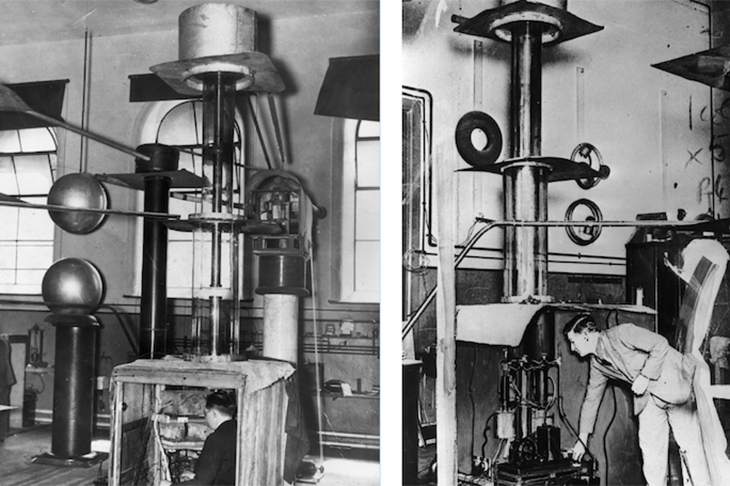

In the 1930s, for example, the race was on to split the atom. As a result, the people that the programme, you felt, would really like to have called ‘the Yanks’ (or possibly ‘our gum-chewing cousins from across the pond’) constructed huge machines to produce the millions of volts they thought would be required. Meanwhile in Britain, John Cockcroft worked out that just 300,000 would do the trick — and built a suitably modest piece of kit out of old tea chests to prove it.

At this stage, Britain was duly leading the world. But then came the war and with it Churchill’s generous decision to let America lead the Allies’ charge for an atomic bomb, with our scientists providing only some much-needed back-up. Sadly, his kindness was repaid with ingratitude when the Americans passed the 1946 McMahon Act forbidding the sharing of atomic secrets with the UK — merely because of a (justified) suspicion that some of our guys were Soviet spies.

The question, then, was whether we’d try to create our own bomb; and the answer was, of course, yes. At which point, enter Ken Johnston, the bomb-maker mentioned at the beginning who, given that he was transforming British fortunes in the late 1940s, must be an awful lot older than he looks. With the aid of a marker pen, he explained in some detail the science involved in imploding plutonium — and, to his obvious delight, was allowed to illustrate his remarks by blowing stuff up.

But in case Ken’s contribution suggested an alarming lack of amateurism, we also met a man who picked up any spilt radioactive material with a shovel — and heard about a Vauxhall car with government plutonium in the back that broke down outside a south London pub.

Even so, Britain exploded an atomic bomb in October 1952, taking care to protect its citizens by doing so just off the Australian coast. Unfortunately, the Americans were already moving on to the far more powerful hydrogen bomb, and it was now the turn of a man called Bryan Taylor to pick up the marker pen and explain nuclear fusion — while also recalling his initial briefing at Aldermaston: ‘The government’s just announced that we’re going to make a hydrogen bomb, but we don’t actually know how to. Have you got any ideas?’

Luckily, Bryan did — and in November 1957, Britain’s own H-bomb worked with sufficient aplomb for the Americans to sign a new information-sharing agreement.

All of this was fine, and often gripping, as far as it went. The trouble was that, with only an hour at its disposal, the programme didn’t have time for much more than the technological-quest aspect. By the end, we understood — or at least had been told about — the basic science. The political background, however, remained somewhere between sketchy and caricatured; and the interviewees were restricted almost entirely to their scientific achievements, with little sense of what their lives were like before, after or even during their bomb-making days.

It’s not often that a TV reviewer wishes a programme had been longer. But had this one run to, say, two hours (or two episodes) the science could surely have been one element in an even richer story.

A few weeks ago, I was in an Islington pub, when a friend staggered the assembled metropolitan types — me and a bloke called Bren — by arguing that the great road-based sitcom of our times isn’t The Trip, in which two successful comedians drive through picturesque parts of Europe; instead, it’s Peter Kay’s Car Share (BBC1, Tuesday), in which a supermarket manager and his female colleague drive to and from work in Bolton.

Naturally I was aghast at the time, but now I’m beginning to wonder whether he might be on to something. I still don’t think The Trip is overrated, but anybody who ever wants to know about British life in 2017 (future generations, present-day politicians, the kind of Americans who think we all have nightly baths run for us by our butlers) should carefully study Car Share. Happily, the rest of us can simply enjoy the perfect blend of scorn and affection with which it regards the irreducible naffness of so much that surrounds us.

Comments