Never before have so many people in so many places collected works of art. In the past decade, the auction houses in particular have made heroic efforts to expand their markets, both by reaching out to emerging economies and by embracing new technologies. Thanks to instant translation by online search engines and live online auction platforms, it is now as easy to buy a work of art offered by an English provincial auction house or a Manhattan dealer while sitting in Guangzhou as it is from Guildford. The international art market has become global, and art is now seen as an asset class for investors.

Given the current performance of the global financial and property markets, it is probably fair to say that more people than ever are tempted to put their money in works of art. Certainly it is an appealing idea. Works of art are more interesting to look at than a safe full of bonds. And, of course, you can hardly lose. That, at least, is what anyone scanning the collecting pages of newspapers or magazines might be forgiven for thinking. Stories of works of art acquired for hundreds and sold for millions are legion, the very stuff of headlines.

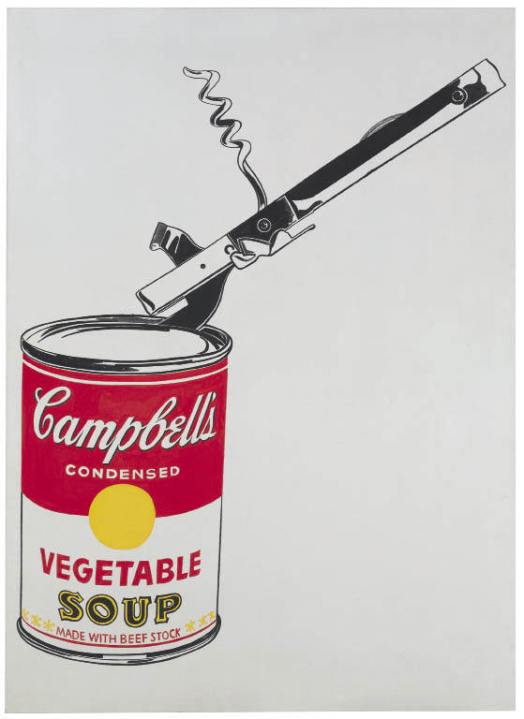

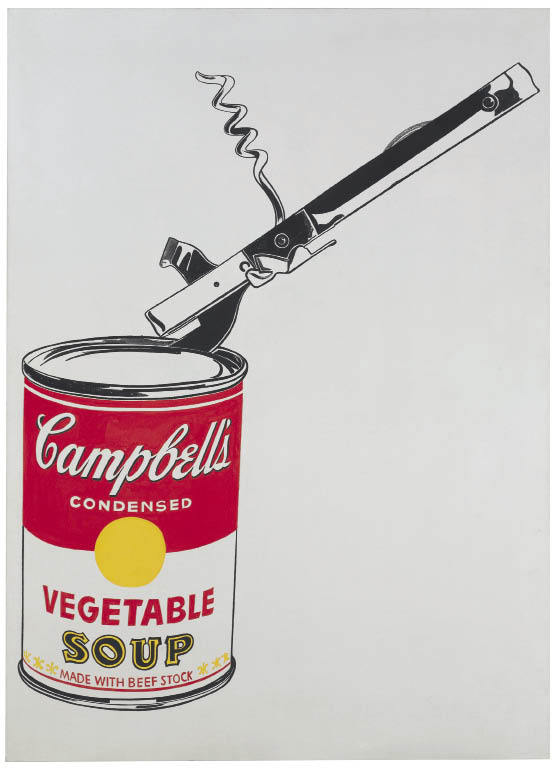

As I write, Christie’s has announced the star turn of its Post-War and Contemporary Art evening sale in New York on 10 November: Andy Warhol’s ‘Big Campbell’s Soup Can with Can Opener (Vegetable)’ of 1962. It made its last auction appearance in 1986 when it was acquired by the London dealer James Mayor for $264,000. His client, Barney Ebsworth, is now selling it with an estimate of $30–50 million.

It is in the art trade’s interest to tell punters the good news — and human nature for collectors to dwell on their successes. Who ever heard a Wall Street trader announce to a room that he had bought a Richard Prince ‘Nurse’ painting for $8 million and sold it for less than $3 million? Yet, as veteran London picture dealer Julian Agnew wryly put it, ‘buying art is a high-risk business’.

There is, inevitably, some correlation between risk and return. The most spectacular returns invariably come from what one might call speculative buying; we might even call it art ‘futures’. That is, buying the work of young, emerging artists and hoping they make the grade, or acquiring the unfashionable and waiting — how long? — for the pendulum of taste to change direction.

A textbook example of how to do the former came recently with the forced sale of selected works from the corporate collections of Lehman Brothers, the investment bank that collapsed in 2008. Although the prices at which works were acquired were not revealed at Sotheby’s September sale in New York, it is clear that many of the lots that had originally been acquired directly from the artists’ gallerists sold for up to 20 times their purchase prices, and some 17 new auction records were achieved for individ-ual artists. One of those records was for the top lot, Julie Mehretu’s dynamic and multi- layered ‘Untitled 1’, which had been acquired at an avant-garde project space in 1991 before the artist found international acclaim, and now sold for just over $1 million. Insiders say that less than $2 million was spent by the bank in acquiring these works of art: they sold for over $12 million.

It is crucial to remember, however, that the presiding genius of the collection was Roy Neuberger, a seasoned, passionate and astute collector whose asset management company Neuberger Berman was taken over by Lehman in 2003. The strategy was to focus on emerging artists and buy, for a relative song, works by good mid-career artists that had failed to sell at auction — a form of bottom-fishing akin to the firm’s dealings in subprime mortgages, perhaps.

Irony came when Damien Hirst’s atypical ‘We’ve Got Style (The Vessel Collection — Blue)’, expected to fetch around $1 million, failed to elicit a single bid. Back in September 2008, on the very day that Lehmans filed for bankruptcy, precipitating meltdown in the money markets, Hirst’s one-man auction at Sotheby’s notched up a record-breaking £70 million. So it’s tempting to suggest that Hirst’s bubble has burst. I see that a butterfly piece that has just been offered at Christie’s London with an estimate of £2.5–3.5 million is from the same series as one sold at Phillips de Pury in 2007 for £4.7 million.

Revealingly, the Lehman sale offered ‘selected’ works from the collection. One can only presume that the auction house chose those works that were most likely to sell well. Most people do not realise the extent to which the big-buck, high-profile sales staged by Sotheby’s and Christie’s are effectively curated. In these difficult times, when confidence is all, the only consignments accepted are those which they believe people will want to buy, and at prices they hope people will pay. There is not much choice but to hold on to the rest. As for the now beleaguered middle market in almost every field, auction buy-in rates of perhaps 50 to 60 per cent are the current norm.

So much for liquidity. Anyone thinking of making a killing in contemporary art should take a look at the storerooms of the world’s contemporary art museums, where rack after rack holds works of art by artists no one these days has heard of. Perhaps only 1 per cent of any art ever sold has truly stood the test of time.

In this sense, the established Old Master market is a safer bet. The big money here is made in discoveries — and again the list is endless. In the last three years alone, London dealers Hazlitt, Gooden & Fox, for one, have shown how expertise and an extensive research library can bag under-catalogued masterpieces, known as ‘sleepers’ in the trade, by the likes of Rembrandt and Titian. But what about the countless speculative purchases that do not turn up trumps and limp back to another obscure auction considerably — and expensively — cleaner?

With Old Masters, where proof of authorship in the form of signatures or documentation is more the exception than the norm, so often it all depends on attribution. Art historians have the habit of not agreeing with one another, and scholarship moves on. A salutary tale is offered by the 15th-century panel discovered in a cottage in Bray that was believed to be by the great Rogier van der Weyden. The National Gallery acquired it in 1967 for the second highest price it had ever paid for a work of art. Now no one believes it is by the master. It is no less wonderful an image for that, but it is considerably less valuable.

The fortunes of whole schools of art rise and fall. One Baroque painting that recently took a bow at auction offers a case in point. Domenichino’s ‘St John the Evangelist’ was bought privately around 1808 for the princely sum of 12,000 guineas. In 1884 no one wanted it even for 735 guineas, and in 1899 it sold for 105 guineas. In 2009 it realised over £9 million. As a rule of thumb, no one re-offering any work of art at auction within a decade is likely to get their money back.

If liquidity is important, this is not the market for you. In fact, the art market is not really a market at all, as each individual work is subject to so many variables, not least of which are issues of quality and condition which depend on knowledge and an experienced eye. This is no game for the uninformed. Caveat emptor.

Comments