Vorticism is often referred to as the only British 20th-century art movement of international importance, but the work of the Vorticists — Wyndham Lewis, Edward Wadsworth, Gaudier-Brzeska and their associates — has up to now not been widely known.

Vorticism is often referred to as the only British 20th-century art movement of international importance, but the work of the Vorticists — Wyndham Lewis, Edward Wadsworth, Gaudier-Brzeska and their associates — has up to now not been widely known. However, the Tate’s show has already been seen in Venice at the Peggy Guggenheim Collection, making it the first ever Vorticist exhibition in Italy, stronghold of Futurism (Vorticism’s rival), and in America, at the Nasher Museum of Art in North Carolina. Vorticism was last shown in the USA in 1917, so this exhibition is making history in a number of ways. I saw it first in Venice, where it looked compact and dynamic in the small white rooms of the Guggenheim. In London it is more spread out, and the effect is correspondingly diffuse.

The movement was short-lived, operating on the brink of war, 1914–15, involved fundamentally with abstraction and the machine ethos, and reacting against the Edwardian status quo by importing the discoveries of European avant-garde art. Radical, combative and energising, it was driven largely by two powerful personalities: Ezra Pound, who named it, and Wyndham Lewis who as the self-styled Enemy was in a state of prolonged artistic rebellion against almost everything. He was joined by the brilliant young French sculptor Henri Gaudier-Brzeska and by such allies as Jacob Epstein, William Roberts, Wadsworth, Helen Saunders, Frederick Etchells and the fauvist painter Jessica Dismorr. Apart from a series of memorable sculptures, Vorticist work tends to be small in scale and consist of gouaches or ink drawings done on paper. Few large paintings from the movement have survived, and doubtless this has also helped to limit its subsequent impact.

The exhibition begins with Epstein’s famous mechanomorphic sculpture ‘Rock Drill’, which is flanked by two columns of wall-stencilled polemic from Lewis’s revolutionary periodical Blast. In the centre of the second room is Gaudier’s great marble ‘Hieratic Head of Ezra Pound’, and the zinging Cubist forms of Bomberg’s painting ‘The Mud Bath’. There’s a fine William Roberts drawing, in chalk and watercolour, ‘The Return of Ulysses’, and C.R.W. Nevinson’s simultanist painting ‘The Arrival’. (Interesting comparison here with the French painter Robert Delaunay.) There’s also plenty of documentary material paying tribute to the Rebel Art Centre, Lewis’s alternative to Roger Fry’s Omega Workshop, appropriate to an age when passionate manifesto and letter-writing was common practice. More sculptures by Epstein and Gaudier fill in the radical background, with a first group of Wadsworth’s powerful rhythmic woodcuts, and a luminously coloured study by Roberts for his lost painting ‘Two-Step’.

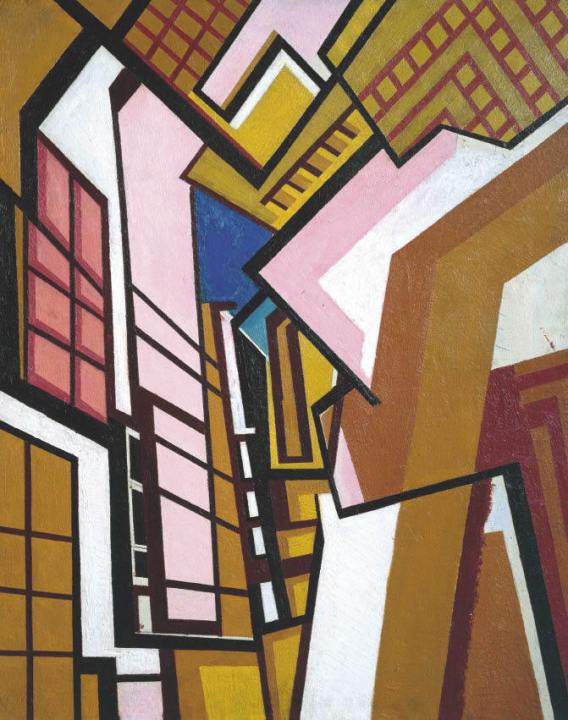

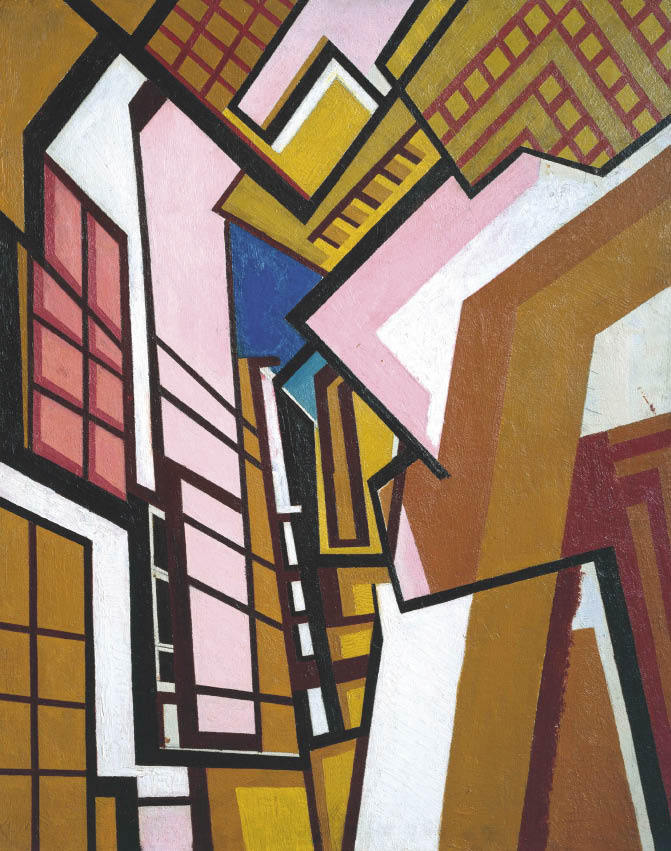

In this part of the exhibition, Wyndham Lewis asserts his hegemony with two important paintings: a major canvas called ‘The Crowd’ and the smaller ‘Workshop’, whose dynamically gridded structure looks a little like the active sails of a windmill. Helen Saunders is well represented, as is Jessica Dismorr, with an intriguingly architectural ‘Abstract Composition’ and a pen drawing of Edinburgh Castle. Etchells’s designs are notable for their clarity, and there are memorable colour arrangements by Dorothy Shakespear (who was married to Pound). The room of ‘Vortographs’ by the American photographer Alvin Langdon Coburn I found of limited interest. The show ends on a high: the last groups of drawings by Lewis, Etchells and Saunders are complemented by a second block of Wadsworth woodcuts, even stronger and more abstract than the first.

Vorticism burst like a shell and then was gone, leaving a number of brilliant fragments behind; but do they add up to much? Worth a trip to Tate Millbank to decide. While you’re there, take a look at Frank Dobson’s remarkable painted plaster figure sculpture, ‘Charnaux Venus’ (1933–4), in the central Duveen galleries. Dobson was among the first sculptors in England to favour a return to direct carving, and was thought of as a leading modernist despite his innate classicism. He helped pave the way for the later radical innovations of Moore and Hepworth, but is largely forgotten today. Undeservedly so, for he is a fine sculptor and draughtsman. ‘Charnaux Venus’ is a tall, elongated beauty, pale as a peeled stick, with purple painted hair and lips, scarcely typical of Dobson’s output, but an eye-catching figure nevertheless.

In one of the galleries off the Duveen is a display until 9 October devoted to John Craxton (1922–2009). A substantial showing of 21 works, it includes drawings and paintings, and a vitrine containing some of his charming illustrated letters. There’s also a short film, made by Craxton’s long-time friend and admirer David Attenborough which pays handsome tribute to the man and the artist. Attenborough quotes Craxton as saying that ‘life is more important than art’, a truth the artist seems to have discovered when he went to live in Greece after the second world war. But the seriousness of Craxton’s work belies this, as does the time and effort he lavished on it. His conversation, sparkling, mischievous and exceptionally wide-ranging, was steeped in art and its centrality to existence. His passionate enthusiasms, his lightly worn connoisseurship, and his whole life proved that art was as essential to him as breathing. If he tended to play down its importance in public pronouncements, this was the typical self-defence mechanism of a man who disliked exhibiting his work and was such a perfectionist that he sometimes took years deliberating over and repainting a canvas.

Craxton rejected the term ‘neo-romantic’ which tended to be attached to his work of the 1940s, although it linked him to his admired older contemporaries Graham Sutherland and John Piper. He accepted that his early work was ‘romantic’, and it’s typified here by ‘Dreamer in Landscape’, in which the vegetation crowds in upon the figure, and ‘Llanthony Abbey’, both 1942, in which the writhing branches and tree roots threaten to overwhelm the buildings.

Craxton’s early vision of the haunted and potentially malign British landscape was soon exchanged for the sun-flooded Aegean: a new palette, and a new style which owed as much to Byzantine art as to the modernist dislocations of Picasso and Miró. Look at the big landscape of Hydra here, with its pulsing built-up surface of intermittent lines and tessellated light. Craxton could paint the joys of life like no other, but in a period when angst was the preferred mood, his work was unfashionable. Now it’s time for a major reassessment of his entire career, and the Tate’s room is a good beginning. Look, particularly, at the lovely drawings of goose, crayfish and hare, and the superb group of 1940s landscapes — three British and the fourth his first Greek painting, ‘Hotel by the Sea’. Note the lightened palette, the Byzantine–Cubist fracturing of space and subject and the new joie de vivre. Craxton knew how to enjoy life, but he also knew how to make art that could lastingly convey his own passionate sense of celebration.

Comments