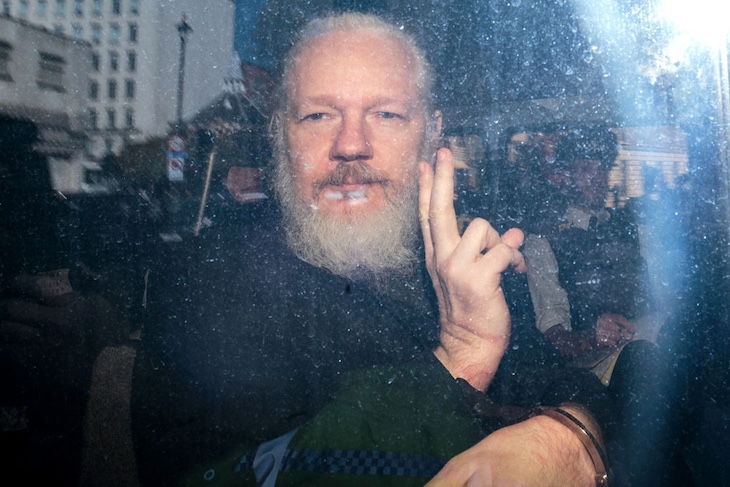

James Cleverly may now be a care-and-maintenance Home Secretary, but even so he will be heaving a sigh of relief as he finally tapes up the file on Julian Assange. The Australian journalist and WikiLeaks founder was on the point of being extradited to the US for revealing state secrets obtained from agents in that country. Last night we heard that Assange’s lawyers had closed a deal with American prosecutors. The arrangement is this. Assange voluntarily surrenders to US officials in the Marianas Islands; he pleads guilty to one offence of revealing US classified information, and gets five years. The court then providentially notices that he has already spent more than that in HMP Belmarsh, gives him credit for it, and releases him to fly to his native Australia.

Assange may have escaped punishment, but other journalists remain much at risk

On one level this is splendid news. There is an obvious element of face-saving for the State Department, which you suspect was almost as weary of the Assange affair as the Home Office here. Meanwhile a journalist is finally saved a long stretch in a US maximum security jail for (in effect) having been a thorn in the flesh of the US military establishment, and left free to write again.

A blow for press freedom? Unfortunately, not really. Even if one writer is free, the position of investigative journalism in Britain remains worryingly precarious.

We have to remember the background. Assange, based here and with no connection whatever to the US, faced extradition and a long American prison sentence for articles published in UK newspapers, on the basis that these articles revealed American military secrets obtained in the US in breach of US law. He had broken no law in this country: our official secrets legislation does not cover information regarded as classified by foreign governments. But that did not matter. Espionage was an extraditable offence, and the State Department had a right to demand his rendition for complicity in it.

Assange may have escaped punishment, but other journalists remain much at risk. In essence, the UK, once an unrepentant promoter of press freedom with a habit of telling foreign governments annoyed at their press coverage politely to go fish, is now in the business of helping foreign states use their official secrets laws against anyone here for what they say, quite lawfully, in this country.

Moreover, there is very little protection available. Our extradition laws give no discretion to the government to intervene even where rendition would be seen by most people as unacceptable. Not only may a person be forcibly sent to another country to face trial for receiving information obtained in breach of its espionage law: provided the extradition paperwork is in order, they must be. The only protection for freedom of speech is a right to invoke Article 10 of the ECHR. But this is a miserly protection at the best of times, and is understandably unlikely to cover many cases of alleged espionage.

Admittedly, it might be said that Britain and the US make common cause in Nato and other matters, and therefore we ought to regard an attack on US secrets as affecting us too. But this, while true, forgets one fact. Assange would have been in exactly the same situation had the requesting country in his case been one of a large number of those listed in the Extradition Act 2003: a category that includes, for instance, Israel, South Africa and Brazil. All those countries have the right to demand the extradition of a British journalist writing here about some political scandal in that country, if it is alleged that they persuaded someone there illegally to access state secrets. This will not do: it is a blatant attack on our right to say and read what we like that needs to be called out at foghorn volume.

Where should we go from here? One solution is reactionary, though none the worse for that. Namely, to return to the situation some 50 years ago, when our extradition law excluded political crimes such as espionage, and in addition gave the Home Secretary an ultimate veto, with no questions asked, over any extradition request. This has strong attractions. It saves us the embarrassment of having to help other countries deal with speech they disapprove of. Furthermore, given the politically sensitive nature of many extradition requests, there is a strong argument for an elected politician rather than a judge having the final say on whether a request should be complied with.

If this will not fly politically (and unfortunately it may well not), a narrower solution would be a specific freedom of speech amendment to our extradition law.

One thing is clear: something must be done. If we seriously believe in the freedom of the British press, we must take steps to make sure that as long as journalists in this country obey our laws, they can write what they damn well please about foreign governments and snap their fingers at any attempt to silence them through official secrets or espionage laws. Other countries, including the United States, already in effect do this. We need to follow their example.

Catch up on the latest Spectator TV:

Comments