If there were regulatory oversight of chess openings, some would come with a litany of disclaimers. ‘You may lose more than your initial gambit.’ ‘Possible side effects may include dizziness and nausea.’ ‘Use at your own risk.’ Nonetheless, such openings as the King’s Gambit, the Dragon Sicilian, or the Botvinnik Semi-Slav often enjoy a cult following. Their devotees tend to be audacious types, who won’t let a few slings and arrows obscure the prospect of a glorious victory. These openings are exciting to play, and not necessarily bad, but they demand a special energy to handle well.

In general, grandmasters prefer more conservative, rugged openings, particularly when they are Black. One notorious example is the Berlin defence, a crucial weapon for Vladimir Kramnik when he wrested the world title from Garry Kasparov in 2000. Rarely played at the time, it quickly came to be seen as a dependable workhorse, on which even a well-prepared opponent would struggle to land a blow.

Top players do deploy more risky openings, but usually as an ambush. At the Candidates tournament in Yekaterinburg last month, Kirill Alekseenko must have been surprised to face the Winawer variation of the French defence, against Ian Nepomniachtchi. The Winawer (which begins 1 e4 e6 2 d4 d5 3 Nc3 Bb4) is not a bad opening at all (it was a favourite of former World Champion Mikhail Botvinnik). But it is double-edged — in seeking counterplay, Black acquiesces to a position with less space, usually without the bishop pair. The ‘poisoned pawn’ subvariation (arising after 4 e5 c5 5 a3 Bxc3+ 6 bxc3 Ne7 7 Qg4, where Black allows Qxg7) is particularly hazardous territory. A couple of years ago, Magnus Carlsen ventured there in a classical game against Anish Giri. The game was drawn, and Carlsen taunted Giri with his tweet: ‘Wanted to use the line in the world blitz, but thought it was too unsound.’ He might as well have said: ‘See, I can get away with anything against you!’

In Yekaterinburg, Alekseenko and Nepomniachtchi drew their game. Boldly, the latter repeated his Winawer just a few days later against Maxime Vachier-Lagrave. ‘MVL’ conducted an energetic attack, shown below, and thereby caught ‘Nepo’ on 4.5/7 at the top of the tournament standings. (The second half of the event is postponed). Though the opening wasn’t solely culpable, Black’s cramped position did sow the seeds of his defeat.

Maxime Vachier-Lagrave–Ian Nepomniachtchi

Yekaterinburg Candidates, March 2020

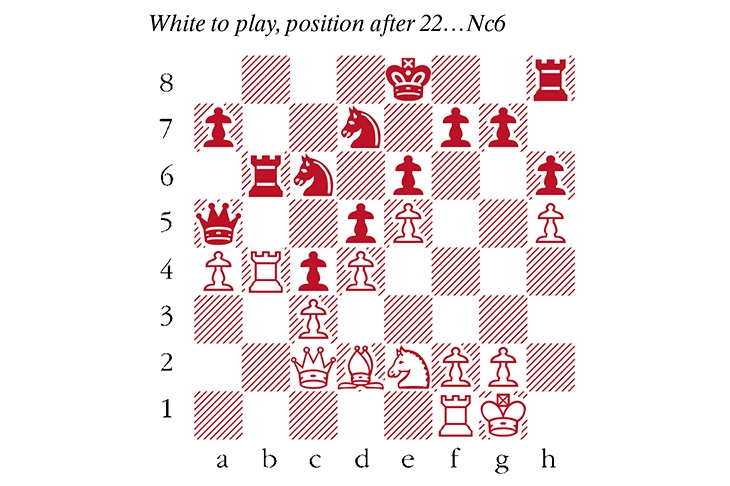

1 e4 e6 2 d4 d5 3 Nc3 Bb4 4 e5 c5 5 a3 Bxc3+ 6 bxc3 Ne7 7 h4 This pawn advance puts long-term pressure on the kingside. 7…Qc7 8 h5 h6 9 Rb1 b6 10 Qg4 Rg8 11 Bb5+ Kf8 After 11…Bd7 12 Bd3, Black can no longer exchange the bishops on a6. 12 Bd3 Ba6 13 dxc5 Bxd3 14 cxd3 Nd7 15 d4 bxc5 16 Qd1 Qa5 17 Bd2 Rb8 18 Ne2 c4 A mistake, taking the pressure off the centre. The Kf8 and Rg8 are clumsy, so White has time to repel Black’s queenside counterplay. 19 O-O Rb6 20 Qc2 Rh8 21 a4 Ke8 22 Rb4 Nc6? (see diagram) 23 f4! Now, 23…Nxb4 24 cxb4 Qa6 (or 24…Rxb4 25 Qc3!) 25 b5 Qc8 26 Bb4 gives White a huge initiative. 23… Ne7 24 Rfb1 f5 25 Rb5 Qa6 26 Bc1 Kf7 27 Ba3 Rhb8 28 Bxe7 Kxe7 29 g4! Blasting through, as 29…fxg4 30 Qg6 cannot be permitted. 29… Rxb5 30 axb5 Rxb5 31 gxf5 Rxb1+ 32 Qxb1 exf5 33 Ng3 Qb6 34 Nxf5+ Kf8 35 Qa1 Black has weak spots on a7, d5 and g7, while the pawn on e5 is a monster. 35…Qe6 36 Ng3 Qg4 37 Kg2 Qxf4 38 Qxa7 Ke7 39 Qa3+ Kd8 40 Qd6 g5 Desperation. 41 hxg6 h5 42 g7 Black resigns

Comments