‘One player on four strings, with a bow.’ That’s what Bach’s six Cello Suites boil down to, says Steven Isserlis. It sounds simple enough, until you add more than 100 editions and 200 recordings into the equation, not to mention countless books, chapters and articles all wrestling with a work Isserlis calls ‘a Bible’ for cellists. And this tussle isn’t just a lofty question of meaning or interpretation either: we’re still arguing about the actual notes. Suddenly the numbers no longer add up.

The cellist Isserlis released his award-winning account of the Cello Suites in 2007. That Hyperion disc (still quietly revelatory, whatever his self-deprecating, occasionally rueful footnotes might suggest) is both the prelude and afterword to the book that now follows. But what seems at first like an elegant extended programme note — an essay that dutifully takes in biography, context, genesis and analysis — smuggles something far more unusual along with it. It’s not a theory, Isserlis stresses, but rather an ‘instinctive reaction’ that carries all the weight of one without its burden. More of that presently.

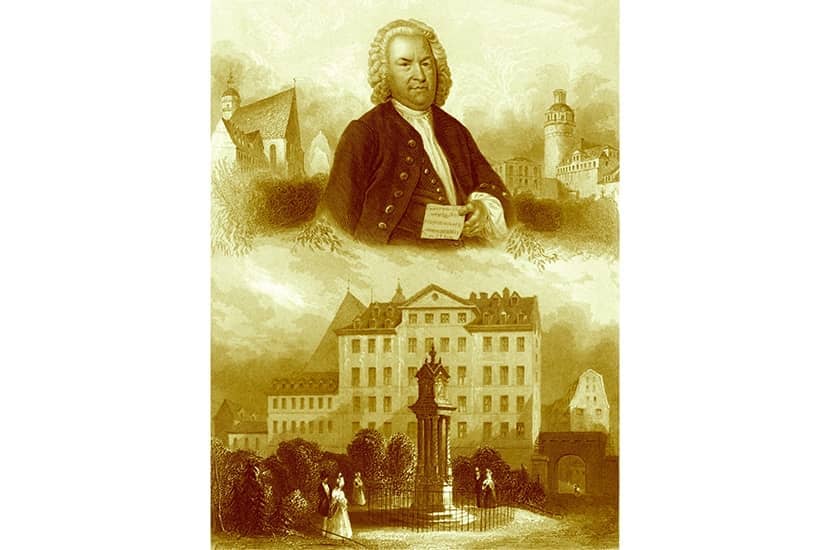

First Isserlis does his due diligence. We hurtle through the composer’s life and career with plenty of energy (and perhaps more exclamation marks than are strictly necessary), including some spicy anecdotes about brawls and women. But it’s far from facile; this is Isserlis’s way of reminding us of Bach the man — that the veneration we feel for his music is a comparatively recent phenomenon. Whether it’s the suspicion of Bach’s ‘mediocre’ skill by the Leipzig authorities, scholarly criticism of his ‘turgid, over-intellectual’ style or the countless scores carelessly lost, leaving the Cello Suites unpublished until 1824 and unrecorded until 1936, the music is gently removed from its display case and reframed as part of the everyday fabric of life and changing fashions.

Such was the work’s casual status for so long that no autograph score survives. Instead, modern editions rely on four manuscripts — each with differences of context, priority, articulation and notes. What does the tiny difference in a slur or a fermata matter to the casual listener? Like William Carlos Williams’s red wheelbarrow, so much depends on them, as Isserlis doesn’t so much argue as demonstrate — with photographs of manuscript details giving us the clues, inviting us to turn musical detective and put them together as we choose.

Isserlis himself, however, has a broader case to make. His ‘theory-that-is-not-a-theory’ explores the meaning of pieces whose original function and application are still unclear. He proposes a narrative context for this unprecedented sequence of six Suites: together they represent a spiritual meditation, taking us from the gentle, cradle-rocking Nativity (Suite No.1), through the D minor anguish of Gethsemane (No. 2) and the musical ‘heart of darkness’ of the Crucifixion (No. 5), to the joy of the Resurrection, celebrated in the pealing bells that open No. 6.

When considered in the context of Heinrich Biber’s earlier Rosary Sonatas, the number symbolism we can trace through the works and the faith that saw Bach head each score with the words Soli Deo Gloria (Glory to God Alone), it’s an appealing case — one only intensified by the blow-by-blow analysis of each Suite that follows. The humour and humanity that Isserlis reveals in the detail of a dotted rhythm or a cadence, the architectural breadth of music whose ‘invisible bassline’ amplifies a single voice into a multitude, the emotional journey ‘through every possible region of the human heart’ that a performance of the Suites represents, all add up to a striking argument.

The Biblical comparison — both in the status of the Suites and their content — is an interesting one. Reverence creates respectful distance, prevents you getting too near. What’s so beguiling about Isserlis’s approach is that he feels the awe and does it anyway. This is a book only a performer could have written; only a cellist who has had his hands in the guts of the thing, weighing every semiquaver and stretching out the sinews of each chord and feeling their tension, could take us this close.

There’s a liberating misdirection to musician-authors. The best of them — the pianist Stephen Hough, the tenor Ian Bostridge, Isserlis himself — write as well as they perform. But because the recording or the concert will always remain the thing itself, the book the supplement, there’s a freedom to both thinking and writing. No scholar could — or would — throw out a theory taking in God, Bach, the universe and everything with such exploratory ease and concision.

And that’s the final joy: this is a short book — a pocket paperback desperate to slip its stiff boards and dustjacket. It’s not intended to be the final word, the oracle-tome on the shelf, taken down occasionally for consultation. It’s a companion book to keep close, to dog-ear and take on the train, the start of a conversation not the end of the argument. After all, as Isserlis acknowledges: ‘The truth lies within the music, not in anything outside it.’

Comments