I was 17 when the Labour party last split, in January 1981, and for a variety of reasons got quite caught up in the moment. It was partly because my father, the author of the 1945 Labour manifesto, was close to the Gang of Four — the original band of defectors — and was one of a hundred people named as supporters of the breakaway group in a full-page ad in the Guardian. But really I was just swept up by the general enthusiasm for the new party that seemed to affect vast swaths of the middle classes. If you recoiled from the economic policies of the Conservative government, which prioritised reducing inflation over full employment, but were equally querulous about the leftward shift of the Labour party, the SDP was an appealing alternative.

I never went as far as becoming a member — I wasn’t a joiner in those days — but was enough of a supporter to join my father on a trip to Warrington in Lancashire to campaign for Roy Jenkins in a by–election about six months later. Jenkins had resigned as a Labour MP in 1977 to become president of the European Commission and, along with Shirley Williams, was one of two members of the Gang of Four without a seat. On the way up in my father’s Vauxhall, he explained that Jenkins didn’t have much hope of winning — Labour had held the seat with a majority of more than 10,000 in 1979 — but the SDP’s leaders felt it was important to field a candidate if the party was going to be taken seriously as a political force.

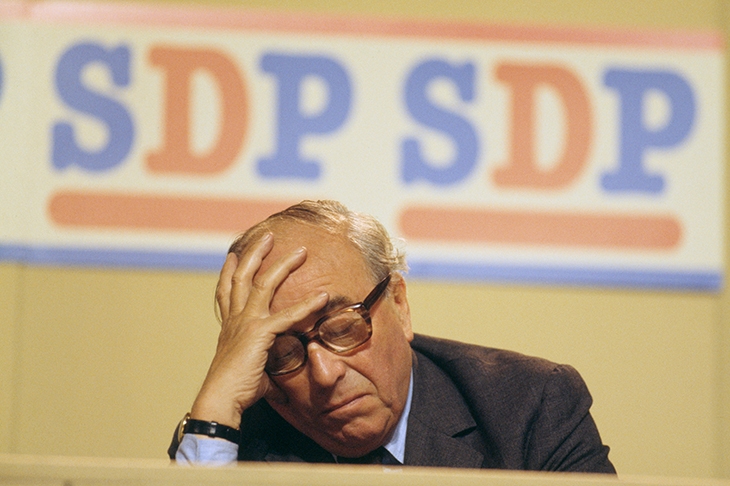

I was nervous about knocking on strangers’ doors, particularly with my eccentric father beside me. He looked like a left-wing intellectual straight out of a J.B. Priestley play: corduroy jacket, knitted tie, horn-rimmed spectacles. He was naturally rather shy — he had a stiff, awkward way of standing, with his hands clasped too tightly behind his back — and this impression was accentuated by a slight stutter.

I, by contrast, was a fully fledged New Romantic, with floppy hair, harlequin trousers and a puffy shirt. What would the good burghers of Warrington make of this odd couple? The fact that our candidate was a lisping, worldly bon vivant — Jenkins was famously fond of clawet and enthused about the gweat vawiety of westaurants in Bwussels — probably wouldn’t help.

‘Don’t worry,’ my father said, as we approached the first gate. ‘The people here aren’t like our neighbours in London. You’ll be amazed by how warm they are.’

Sure enough, the first door was opened by an elderly gent who couldn’t have been friendlier. He’d been a Labour voter all his life, but wasn’t impressed by Tony Benn or his political allies in the trade union movement. Then again, he didn’t much care for the liberal, cosmopolitan values of the SDP either. He wasn’t keen on the Common Market and was worried about immigration. My father tried to persuade him to vote for Jenkins to send a message to Labour that it was headed in the wrong direction, and when we left we put him down as a ‘maybe’ on the canvas return sheet.

This set the pattern for the rest of the day. Everyone whose door we knocked on was happy to see us and listened politely as my father made his pitch. But the SDP just wasn’t causing the same excitement in Lancashire as it was in the sitting rooms and open-plan kitchens of north London. We encountered plenty of disillusionment with the Labour party, but it was from traditional working-class voters who were more concerned about its drift to the left on social issues than about the economy. They were the sort of people who, 35 years later, would vote to leave the European Union (Leave beat Remain in Warrington by 55 per cent to 45 per cent). If there was headroom for a new political entity in the north of England in 1981, it was for a party more like Ukip — left of centre on public services like the NHS, but right of centre on crime, immigration and welfare.

Jenkins lost by a few thousand votes, but went on to win a by–election in Glasgow Hillhead the following year. My flirtation with the SDP ended with the Falklands War, after which Margaret Thatcher could do no wrong in my eyes, and my father eventually re-joined the Labour party. I expect there will be an initial surge of enthusiasm for the Independent Group too, but it won’t last, and for exactly the same reason. There’s space in British politics for a populist alternative to the two mainstream parties, but this won’t fill it.

Comments