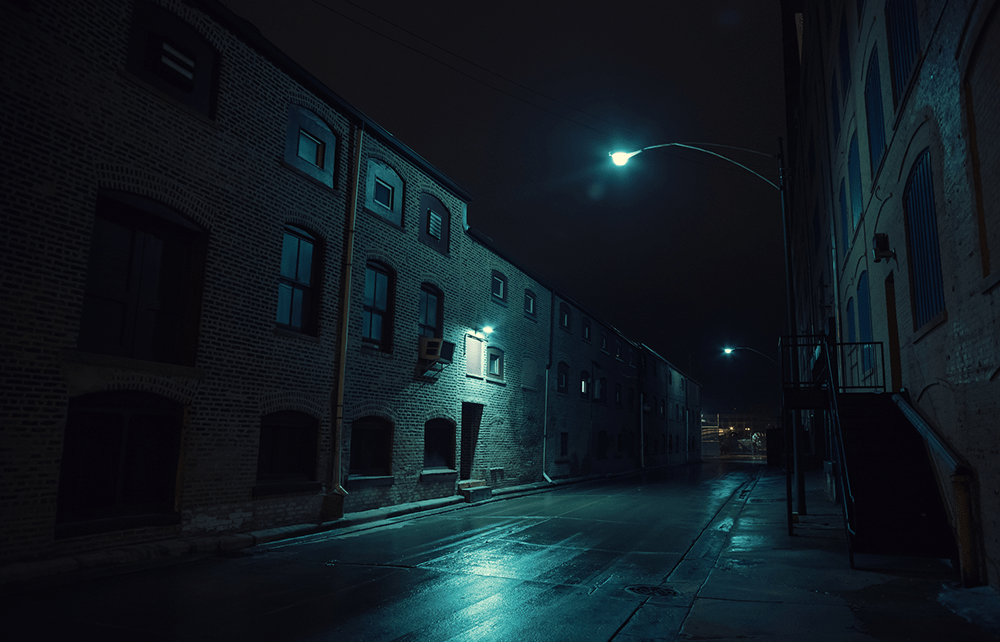

Being mugged changes you forever. My encounter with highwaymen occurred three decades ago in a south London street, in the early evening as I emerged from a corner-shop. I was transferring some coins from one hand to the other when four men pounced on me from behind, tipped me over and dragged me down a lane between a derelict pub and a car park. I lay there surrounded, waiting for the inevitable violence, but my attackers grabbed the cash that had fallen from my hands and melted away into the night.

I always avoid high-risk areas: towpaths, churchyards, parks at dusk – anywhere without cameras

I was left feeling shocked, humiliated and grateful I’d escaped with my life. Sadism was part of their motive, I expect. They wanted to enjoy the thrill of wielding absolute power over a random stranger. Ever since, I’ve lived my life as a high-wire act. It could happen again, at any time. I still cross the street if I see four unfamiliar males approaching me. Three is OK. So is five. But a quartet unsettles me. And the four bandits changed my outdoor dress-code permanently. On the night of the ambush I was wearing patent leather shoes from a charity shop and a midnight blue overcoat. I never used these garments again and I adopted the invisible apparel of the underclass: frayed jumper, tattered jeans, crime-scene jacket, dead man’s shoes.

Even now, I prefer this costume because it feels safer and it signals to potential muggers that frisking me at knifepoint will yield nothing of value. But if you dress like a vagrant, you get treated like one. A decade ago, during the interval of a play in Islington, I stepped outside and crouched down on the pavement beside a wall. Moments later I became aware of a few lads on bikes, whispering among themselves. They were planning to rob me. I stood up and walked back into the theatre realising, with dismay, that my withdrawal had taught them a valuable lesson in criminality: don’t plot a theft within earshot of your victim.

Mugging is a skill, like any other, and it rewards the experienced practitioner. Thieves learn on the job and I do my best to avoid being part of the curriculum. A couple of years back, a young robber launched himself at me from a roadside wall where he was sitting with two accomplices. To my surprise, and to his, he bounced off me like a foam boomerang and landed on the pavement. He was about 15 and his physique hadn’t acquired the resilience and density that come with age. Next time, he’ll carry a weapon, or hide himself better, or teach his comrades the importance of attacking simultaneously and with overwhelming force.

I always avoid high-risk areas: towpaths, churchyards, public parks at dusk – anywhere without witnesses or spy cameras. When I go abroad, I’m sceptical of smiling locals who inform me that thieves are lurking around the next corner but one. I assume I’m being steered towards the danger rather than away from it. In Istanbul, at the age of 21, I walked into a trap of my own design by strolling through Sultanahmet Square trying to sell a pack of 200 duty-free Marlboro. A friendly buyer agreed to pay cash and led me down a side alley to complete the deal. He then placed his wrists alongside each other, to indicate ‘handcuffs’, and blew a police whistle. I dropped the cigarettes and fled. My fault.

I’m told by lawyers that rainfall is a blessing to muggers. When the heavens open, everyone rushes indoors and the few who brave the elements pull their hat brims down low or carry umbrellas which impede their vision. In court, their testimony is easy to demolish. An experienced mugger can rob anyone on a rainy night with impunity.

I recently returned to the London street where my attackers pounced. Gentrification has reached the area and the defunct pub, all spruced up now, serves wheat beer to computer wizards with ring-pull noses. Out in the lane, between the parked e-scooters, I found the spot where the thieves had dragged me and where I lay helpless, expecting to be kicked or knifed to death.

I remember with perfect clarity what I felt at that moment. Not fear or anger. A sort of calmness entered my mind, as if some un-resolved difficulty that had been troubling me for ages had just been settled. Or as if I’d heard a whisper explaining a minor problem that I had foolishly imagined was enormous. ‘Yes, I see now. How simple,’ my inner voice said to me. ‘That was what this is about.’ That referred to life and this referred to death. And it barely mattered at all. Like

a sweet wrapper blowing into the sea.

Comments