I have been invited to Moscow by the Russian Orthodox patriarchate because the organiser is a fan of my podcast. Everyone at home thinks I am either dangerous or mad. My mother is convinced I’m going to be bumped off by the FSB or killed by a drone. Others claim I have become a useful idiot of the evil dictator Putler because the patriarchate are merely his stooges. ‘Is that true?’ I ask the patriarchate’s media affairs guy. ‘Well, under Peter the Great we were run by the government. And under communism we weren’t allowed to exist. So you could argue that, historically, we’re about as independent as we’ve ever been.’ When I put the same question to an archbishop, his response is more forthright. His parents, who grew up in the Soviet Union but now live in France, tell him they’re sick to death of the western media’s relentlessly negative take on Russia. ‘We’ve not seen such propaganda since the days of Brezhnev.’

Obviously you’re not going to believe anything positive that I say about Russia. But aren’t we in danger of throwing the baby out with the bathwater? For example, one of the patriarchate’s main concerns is the persecution of their brothers in Moldova. The Chisinau government wants to join the EU and is busy sucking up to its future overlords by harassing the Moldovan Orthodox Church, which, though autonomous, is mostly closely tied to the values and traditions of Russia rather than the liberal West. Moldovan priests who won’t support gay marriage, LGBT parades or abortion – almost all of them reflecting the view of their parishioners – are monitored and tailed, as in Soviet times. When they go to the airport, a monk tells me, they are held for questioning for hours until their interrogators are sure that they have missed their flights. Some priests have been beaten up. Church buildings are being seized illegally.

Do we really want to be siding with the EU progressives on this one? I’ve been to Moldova. Outside the capital, it’s very rustic, deeply traditional and devout. Unlike in the secular West, the Orthodox are still very much alive to the distinction between the temporal and the spiritual. Most Orthodox Moldovans want to keep the old ways – and the old calendar – and just because the Russkies are supporting them doesn’t mean they are wrong.

Though I’m not planning on abandoning my Anglican parish in Northamptonshire, with its six or seven picturesque medieval churches and its Book of Common Prayer communion services, I do find the mysteries of Orthodoxy awfully seductive. And I love its saints, such as St Matrona, the blind Revolution-era peasant canonised because of her visionary and healing powers. I joined one of the long lines at the Church of the Protecting Veil to pray for a relative’s health. While we waited, a babushka in her headscarf – all the women still wear headscarves on holy ground – showed me how to make the sign of the cross (forehead, belly button, right breast, left breast, with the tips of the thumb and two fingers squashed to form a point). You want to get things right for the revered saints.

There were two queues. Twenty minutes for the icon on the wall outside the church, an hour for St Matrona’s bones, so I chose the former. But when I’d done this, our guide had a quiet word with the person guarding the bones and, being an esteemed foreign visitor, I was allowed to skip to the front and venerate the actual relic. You’d think the people I’d queue-barged would mind, but they didn’t. The longer you’ve waited, the more you’ve shown your reverence – so cheats haven’t really gained an advantage.

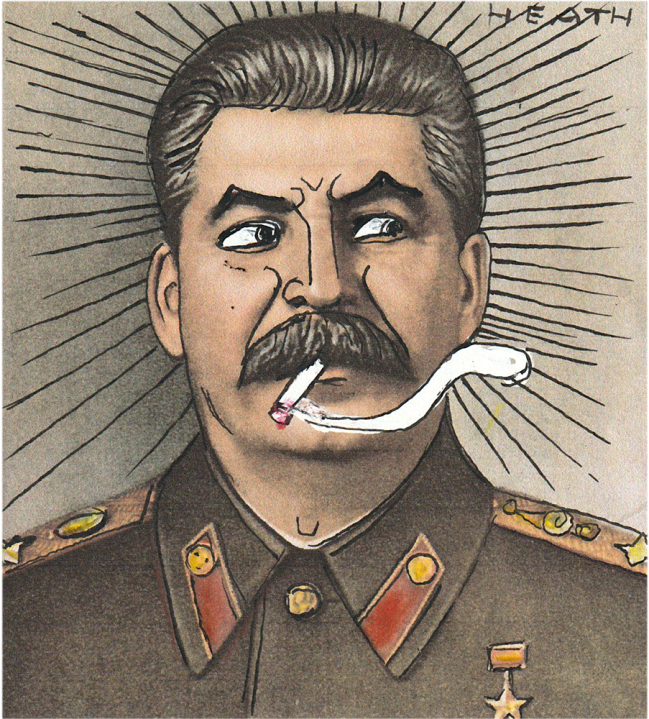

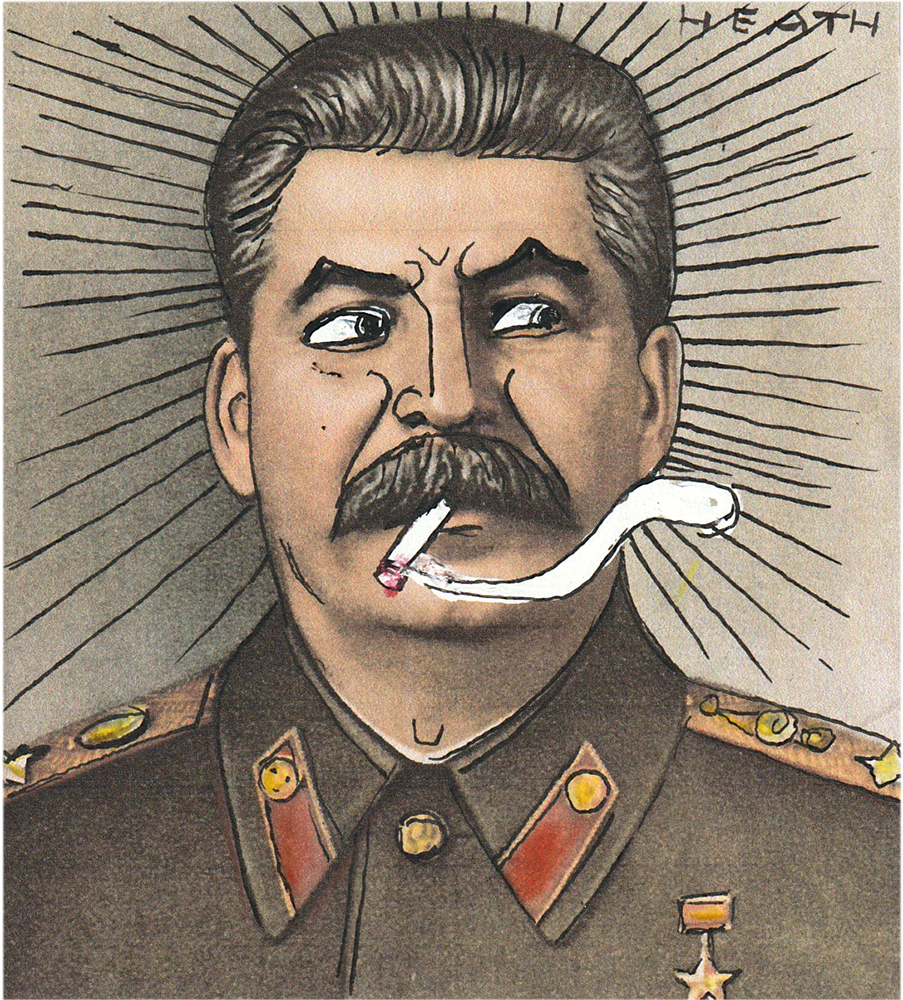

Russia is great. You’re not going to believe me, obviously, but the streets are clean and safe, with no danger of London-style stabbings or mobile-phone jackings; public transport works (and the Moscow Underground, with its beautiful, if not un-Stalinist, themed stations is the best in the world); there are covered markets selling delicious organic produce (from raw milk to fresh fish, pomegranates to wild mushrooms); the people are reserved but polite, thoughtful and often deeply cultured; and, judging by the bustle in the many excellent restaurants along the Arbat and Bolshaya Nikitskaya, the shape of the economy isn’t half as bad as we’ve been led to believe. Perhaps the 13 per cent tax rate for the vast majority of the population has something to do with this. Or maybe it’s that, being an oil and gas producer, Russia doesn’t have much time for net zero, so it’s not waging war on motorists, air travellers or affordable heating.

But Moscow is no place to be lost if, like me, your only Russian sentence is: ‘The hedgehog lives in the park.’ Possibly because of the jamming technology used to ward off drone attacks, satnavs barely work in the city centre, so lost immigrant taxi drivers from the Stans often cause traffic chaos, and if you’re on foot, Google Maps is not your friend. Eventually a kind young man, out with his girlfriend, took mercy on my plight and walked with me ten minutes out of his way to my destination. ‘How do you like Moscow?’ he asked via his mobile phone translator. ‘Amazing!’ I said. ‘You surprise me,’ he replied. Sad. Even the Russians believe the nonsense that things are better in the West.

Comments