This book deserves to be named in the same breath as those two great classics of royal biography, Roger Fulford’s Royal Dukes and James Pope-Hennessy’s Queen Mary. It shares with those two masterpieces the double advantage of being profoundly learned and a cracking good read. There is scarcely a paragraph of Bertie which does not contain new material, most of it culled from the Royal Archives, but also from a wide variety of other sources, including the diaries — which Jane Ridley discovered in the Royal College of Physicians — of Bertie’s German medic, Dr Sieveking.

Its most affecting passages — and there are many — derive their power from the accumulation of carefully gathered detail. In the chapter entitled ‘Annus Horribilis’, we read of the premature birth of Bertie and Alix’s last child, little Prince John, who lived just 24 hours. The sobbing Alix kept the baby with her in bed and held his hand which ‘was warm, though his head was cold and his limbs were stiffening’. Princess Alexandra was 26 when this happened. She had spent 48 months — that is, half — of her married life pregnant, and now, after repeated pregnancies and still births, and with five surviving children, she was forbidden by the doctors to have any more.

Apart from the pains of childbirth, Alix, daughter of the King of Denmark, was obliged from the first to tolerate an adulterous, playboy husband. Ridley pulls no punches in her analysis of Alix’s illnesses, and although she does not go so far as to say that she contracted syphilis from her husband, she plants the idea very firmly in our minds that the mysterious troubles with her knee, and her deafness, might have been the result of that dreadful, and in those days incurable, condition. She lets fall Freud’s view that ‘men seek out prostitutes to revenge themselves on their mothers’. (Later in the book, and to me a little bafflingly, she says that one does not need to be a Freudian to connect his late middle-age ‘impotence in the bedroom’ with ‘his new passion: horse racing’. How will Elizabeth II read this sentence?)

For the first half of the story, we are in the presence of an appallingly selfish young man whose only accomplishments to date have been the invention of turn-up trousers and the development of the wholesale pheasant-cull known as the Sandringham shoot. The casual liaisons multiply. Alix, deaf, lame and prematurely aged, Harriet Mordaunt dying in a lunatic asylum and Susan Vane-Tempest apparently dead from syphilis are the ‘unsettling reminders of the human cost of Bertie’s pleasure’. As Bertie’s waistline bulged, the queue of women lengthened: they included Jennie Churchill (Winston’s mother), Lillie Langtry, and Daisy Brooke, perhaps the most spirited of all the mistresses.

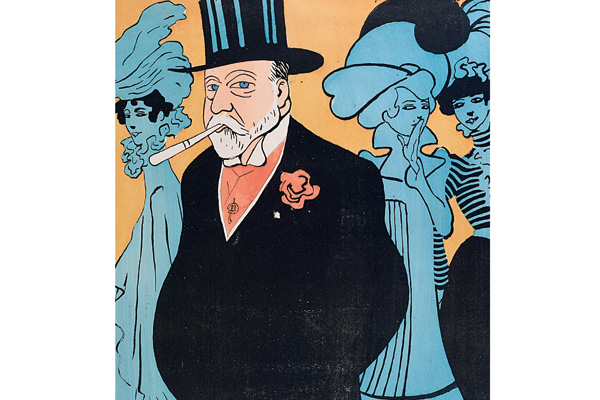

When he eventually, at the age of 59, became King, and Alix knelt before him with the word ‘Sire!’, Edward VII growled, in his cigar-roasted guttural voice, and in German: ‘It has come too late.’ This moment comes late, but not too late, in Ridley’s book. Her account of Edward’s virtues as a monarch and as a man, are generous — though this author’s praise is never undiluted: ‘The accession of an overweight 59-year-old philanderer hardly thrilled the imagination. Yet he possessed charisma.’

Charming he could be, but, as this book makes plain, as he became fatter and older, the King’s irascibility could easily rival that of his sainted Mama, and lateness or hitches in arrangements could cause painful eruptions.

The analysis of Edward’s relationship with Arthur Balfour and Sir Henry Campbell-Bannerman as prime ministers, and the grasp of European politics in the Edwardian era, are matchless. Edward VII was an attentive, intelligent diplomat, one not without moral courage as when — in defiance of his sheepish ministers — he raised the matter of tsarist pogroms against the Jews in his discussions with Stolypin, prime minister of Russia. (Ridley is good in general on Bertie’s philo- semitism.)

The book ends with a superbly concise survey of previous biographies of Edward VII. It is a coded analysis of the taboos and conventions governing royal biographies per se, pointing out that Philip Magnus, writing as late as 1964, was ‘unable to address the prince’s private life, even if he had wished to do so. Not only were the papers missing; the stories were still too sensitive.’

When last seen, the Round Tower at Windsor, where the archives are enshrined, was still standing, but they must have felt rumblings in the very foundations as Professor Ridley arrived every morning with her notebook. She is fair to the two chief protagonists, Bertie and his long-suffering Danish wife, but to very few other members of the royal family. Queen Victoria is Ridley’s bête noire. Although we are told that Victoria is not the model for Lewis Carroll’s Queen of Hearts, her ‘bewildering changes of mood’ are compared to that two-dimensional figurine and even when it is grudgingly admitted that Victoria worked very hard, this has to be expressed as: ‘The menopausal monarch was no slouch.’ It is a surprise to read a repetition of Bagehot’s judgment that ‘Queen Victoria’s domestic virtues were admirable’ after 100 pages in which she has been depicted as a monster of hysterical selfishness.

Indeed, this is a book which bristles with prejudices and arbitrary judgments. No one would guess from its first 60 pages, with their Gibbonian version of Victoria and Albert’s marriage, that the Prince Consort was a man of exquisite taste, that he was an accomplished composer, that he had organised the Great Exhibition, or that he had guided his wife into an understanding of contemporary politics. So much does Ridley dislike Prince Albert that, even as he is dying, she piles on disparaging epithets. His vomit was ‘foul-smelling’, as if other people’s had the aroma of gardenias. His corpse was dressed in the uniform of a Field Marshal. ‘Even in death he was on duty,’ Ridley tartly comments, as though the poor workaholic prince had fussily kitted himself out in his own coffin.

Germany and Germans are vilified on almost every page. (Princess Alice became engaged to Prince Louis of Hesse, ‘a dull boy with a dull family in a dull country’.) In a rare descent into cliché, Ridley says that Prince Albert ‘repackaged’ [the royal family] as ‘a middle-class idyll’. On another page, she describes him as a ‘model of middle-class virtue’. It pleased English mockers from the beginning to say that Prince Albert, whose undiluted royal lineage stretched back to the time of Charlemagne, who built two palaces, and who was a great art collector,was ‘middle class’; what they seem to have meant by the phrase is that he was not an adulterer.

Every page of Bertie is entertaining and tells us something new; and it is surely true to say that royal biography, as a genre, will never be quite the same again. I am prepared, however, to make a prediction. When the sad day dawns, and some reverent-minded committee is looking around for an official biographer of our own dear Queen, I do not think that Jane Ridley will make it to the shortlist.

Comments