I have only been to Alexandria once, some years ago, when Hosni Mubarak was still in power, but it struck me as a sad city. Of course the library was not the library. The lighthouse was not the lighthouse. The city was not the city. I looked around for the remnants of the Greeks who had made it their own, but there seemed little left of them.

Is there a cause we are financing so considerable it is decent to pass the cheque on to the next generations?

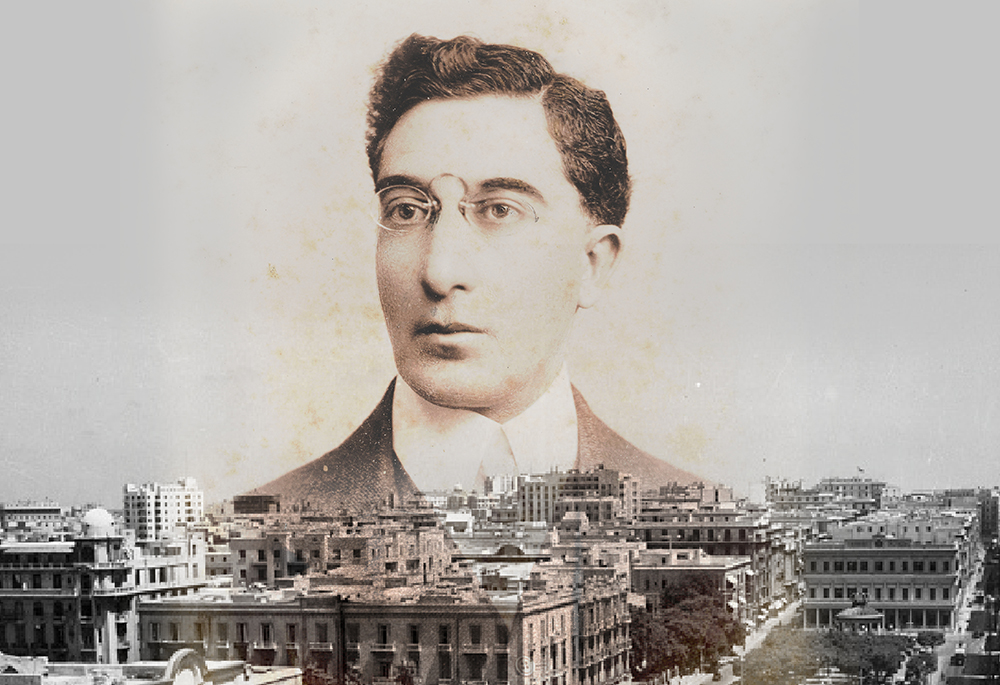

Alexandria was on my mind again this week while reading a new biography of the city’s most famous modern poet, Constantine Cavafy (1863-1933). He was part of that world which migrated across the Mediterranean. Born in Alexandria, Cavafy and his family spent time in Liverpool before moving back to Egypt, fleeing to Constantinople, before returning to the already fading city. His social circles included the sort of Greek families that had fled Smyrna, Chios and other massacres committed by the Turks.

As the family trading business declined, Constantine, his siblings and finally their children lived within ever more slender means. But it was a letter from Cavafy to his most important non-Greek literary friend that struck me most. The poet and E.M. Forster became friends in the 1910s when Forster was in Alexandria. Forster did more than anyone else to bring Cavafy’s work out to a non-Greek-speaking audience. One letter that Cavafy wrote to Forster seemed particularly notable.

He wrote: ‘Never forget about the Greeks that we are bankrupt. That is the difference between us and the ancient Greeks and, my dear Forster, between us and yourselves. Pray, my dear Forster, that you – you English with your capacity for adventure – never lose your capital, otherwise you will resemble us, restless, shifty liars.’

I suppose Cavafy’s warning brought to mind, among other things, our former deputy prime minister Angela Rayner, specifically her unpaid £40,000 stamp duty, second-home issue. But it also brought wafts of those other great scandals of recent public life, such as the SNP’s Nicola Sturgeon and her husband having to answer questions a couple of years back about the use of party funds to purchase a luxury camper van worth a six-figure sum.

American politicians, at least, have a certain boldness in their financial aspirations. Nancy Pelosi, for instance, has managed to acquire a wealth running into hundreds of millions during her time in office. Her investments have consistently outperformed those of even the canniest hedge funds. But Pelosi has never faced any special censure over this. Whatever the rights or wrongs of her dealings, there is a certain grandiosity among US lawmakers in their search for wealth.

Our own politicians seem to fit into a different category, and I wonder if it doesn’t have something to do with what Cavafy was warning Forster about.

According to the Office for National Statistics, the UK had to borrow £60 billion in the financial year up to July – almost £7 billion more than the same time last year – and spent £41 billion to service its debt. Like most fiscal conservatives, I am slightly amazed at the financial and moral presumptions that lie behind this. Is there something we are doing with our money as a nation that is so tremendous that it makes it worth running up this kind of debt? Is there a cause we are financing so considerable that it is decent to pass the cheque on to the next generations?

It is no better across the Channel. The French may have a government less stable than our own, but they have all the same problems. France is also in a debt crisis. And the French parliament, like the British parliament, remains resolutely opposed to doing the things a responsible country would do to address it, such as cutting the astronomical spending on every arm of an increasingly corrupted and incompetent welfare state.

In France, the right, as much as the left, is given to promising an unending money-spigot to voters. In fact, right-wing parties are in some ways worse, cynically recognising that one way to achieve success at the ballot box is to tack right on identity but left on economics.

Yet it is not as though the continent’s politicians don’t realise the realities we face. It is 13 years since Angela Merkel said something true to the Financial Times: ‘If Europe today accounts for just over 7 per cent of the world’s population, produces around 25 per cent of global GDP and has to finance 50 per cent of global social spending, then it’s obvious that it will have to work very hard to maintain its prosperity and way of life.’ Many people nodded sagely, but in the years that followed even Merkel made sure all those figures went in the wrong direction.

Since 2012 we have vastly increased the numbers who have come here, Europe’s share of global GDP has gone down some 10 percentage points, and we have hiked our welfare spending to such a sum that we now even extend the state’s munificence to people who have broken into our countries and never contributed anything to them. Whether peoplein Britain or Europe have actually spent the past 13 years working hard to maintain our way of life is a matter of opinion.

I wanted to pull these threads together to say this: it is clear that we in Britain and Europe are indeed losing our capital. In part because we do seem to have lost our capacity for adventure – content instead to eke out what money we can in whatever time there is, with ever lower aspirations for the future. It could be turned around, of course, but not without a Herculean desire to do so and a sincere recognition of the point we are other-wise heading towards.

What is that point? I would say it is a time when our cities will also not be our cities. And when we too have a preponderance – not least in our political life – of the type of people that the poet warned about: restless, shifty liars.

Comments