About six months ago I was contacted by Big Brother Watch, the civil liberties campaign group, and asked if I wanted to help with an investigation into the surveillance of critics of the government’s pandemic response by state agencies. Would I submit subject access requests to different Whitehall departments to see if I was among the critics of the government’s pandemic response who’d been monitored by the Counter Disinformation Unit, the Rapid Response Unit, the Intelligence and Communications Unit and the 77th Brigade?

I thought it unlikely, but decided to play along and on Monday night Big Brother Watch published its report revealing that I was one of the dozens of journalists, scientists and MPs who’d been spied on in this way. Others included Peter Hitchens, Julia Hartley-Brewer, Carl Heneghan, Tom Jefferson and David Davis. It’s pretty extraordinary that members of Boris Johnson’s government managed to convince the people working in these agencies, some of them with a background in the security services, that those of us who questioned the wisdom of the lockdown policy and vaccine passports were potentially dangerous actors whom the state needed protecting from.

They did this by branding our scepticism ‘disinformation’ or ‘misinformation’ – or by squashing the two together under the heading of ‘mis/disinformation’. The reason for merging these categories is that some of these agencies were originally set up to protect the integrity of British democracy from hostile state actors spreading false information to influence elections. That’s textbook ‘disinformation’ and, on the face of it, has little connection with, say, an Oxford medical professor writing an article for The Spectator questioning the evidential basis for the ‘rule of six’, which is then shared on social media. But if you’re the minister responsible for defending this policy, you can first label the article ‘misinformation’, then claim it falls into the category of ‘mis/disinformation’, then persuade the Rapid Response Unit (RRU) to monitor the professor’s social media activity and report back. As the author of the Big Brother Watch report says, that’s a ‘concerning level of mission creep’.

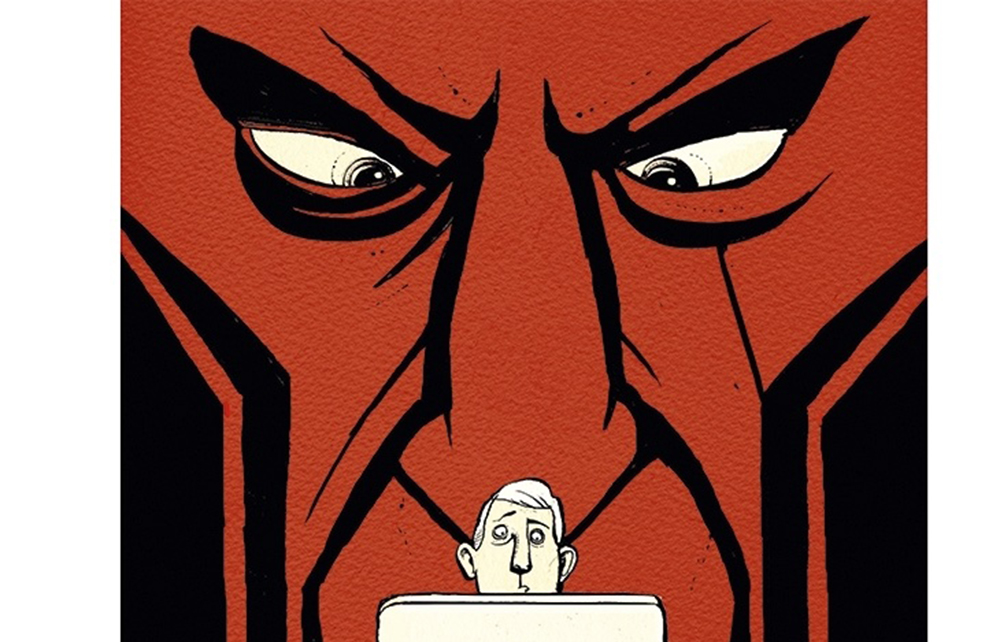

The Rubicon was crossed when the government convinced these units we were a danger to the state

We know the RRU submitted reports to the Cabinet Office about Heneghan and Jefferson because that was disclosed in response to Professor Heneghan’s subject access request. But we don’t know if someone in the Cabinet Office used the department’s ‘trusted flagger’ status to ask Facebook to label a post about a subsequent Spectator article by them as ‘false’, which it did. That piece was about a control trial in Denmark which concluded masks did little to stop Covid transmission.

My subject access requests reveal that the Counter Disinformation Unit recommended against asking Twitter to remove a tweet of mine about an anti-vaccine passport petition, cautioning that there would be ‘freedom of speech implications’. I imagine that’s a reference to my status as the director of the Free Speech Union. ‘It is worrying that government officials were considering to recommend that a foreign Big Tech giant censored a British journalist,’ notes the author of the report, ‘only opting not to on account of the individual’s profile.’ It’s a safe bet that critics of government policy with lower profiles were not so lucky.

Reading the report, you’re left with the impression of a government that had few qualms about using security agencies to spy on its domestic political opponents, or leveraging its access to Big Tech to silence them. But, frustratingly, there’s no single revelation scandalous enough to trigger an official inquiry. That may be because the Whitehall departments decided to hold the juiciest details back, or because nothing outrageous happened.

But that’s to miss the point. To my mind, the Rubicon was crossed when the government convinced the people running these units that critics of the powers it granted itself during the pandemic were a danger to the state. Once it had done that, we were fair game. On this occasion, these agencies may not have gone beyond monitoring our journalistic and social media activities, but what’s to stop them going further next time? One of the reasons they acted with a degree of constraint may be because many of the people they were monitoring were conservatives and had friends in the government. What if a Labour government decides we’re in the midst of a ‘climate emergency’ and anyone who criticises its policies is trafficking ‘mis/disinformation’? In those circumstances, I suspect Hitchens, Hartley-Brewer and I would have a much tougher time.

Comments