With bird books the more personal the better. Joe Shute was once a crime correspondent and is today a Telegraph senior staff feature writer. It is his investigative journalism, a series of meetings with people who deal with ravens first-hand, which provides novelty. Historical, mythological and other diversions add ballast.

In the prologue he writes: ‘I was born in 1984, making me the flag-bearer of a strange generation.’ Raised comfortably and lovingly in London, his future seemed serene. Then ‘came the financial crash of 2007; and with it the collapse of all the misplaced entitlement of my youth… Rather than better, it was going to get far worse’.

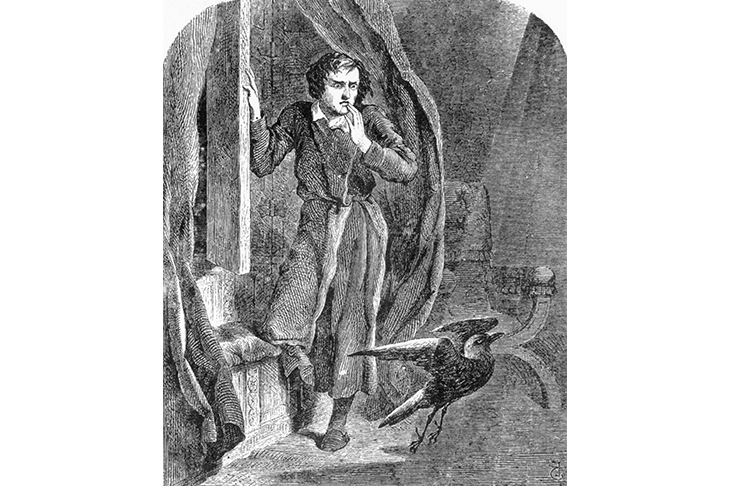

At this juncture, he found solace in birds in the Yorkshire countryside. ‘Learning more about birds helped me to become less fearful of my own world, even as it became an increasingly savage place to live in.’ His hopes are pinned to the raven. Recent research has lent scientific authority to the immemorial belief that, alone of its kind, it has foresight. ‘Now this bird of augury is back, I wonder what it sees for our own dark times,’ writes Shute.

The book celebrates the increase in numbers and range of British ravens. The 20th century found them confined to the western margins. Latest data (2008–11) showed breeding pairs in every English county, with 700 in North Wales and 6,000 in Scotland. Centuries ago they and red kites kept the streets clean of anything edible; now they are back in cities too, notably in Bristol. In London they have not bred since 1845, but re-colonisation seems imminent. This does not include the Tower of London’s famous captive colony, legendary guardians of our freedom; in fact a Victorian inspired tourist attraction accommodated by Philip Chang, exotic animal providers.

Ravens have long been associated with exalted spirituality as well as death and doom. Vikings regarded them as sacred, their Presbyterian descendants as ‘the Devil’s own bairns’. The rich pickings they found on battlefields was one of their more sinister traits. That they were and are killed for good reason is confirmed when Shute visits a New Forest pig farm and, most gruesomely, a Caithness sheep farm. To his journalistic credit he reports the unpalatable facts, such as the lamb unable to suckle because a raven had torn out its tongue. Ravens scavenge but they also kill. They go for eyes and bottoms first, cornering the victims, even full-grown sheep, like dogs. ‘Ravens are really different from other birds… I would say they are evil,’ he was told.

They are legally protected, so to kill them requires a special licence. A local petition to have that rule lifted attracted 2,300 signatories; 27,000 global counter-petitioners signed online; meanwhile the RSPB and Scottish Natural Heritage drag their feet. It hardly needs saying that ravens prey on other birds. Shute’s reporting takes precedence when he admits a former gamekeeper turned prominent raven breeder found ‘no dichotomy between shooting and loving birds’. The distinction of the literary and artistic legacy of our sporting naturalists and countrymen would confirm this truth.

In the raven’s defence he tells several stories which reflect the bird’s endearing characteristics: mischievousness, playfulness, mimicry. Truman Capote had a pet raven, Lola, which he suspected of hiding a guest’s false teeth. He placed his gold signet ring on a table and spied developments. When the raven thought the way was clear it grabbed the ring and hid it in the library behind The Complete Jane Austen. Capote listed the cache revealed: among other things, his best cufflinks, long-lost car keys, the first page of a short story, and the teeth.

Ravens enjoy sliding down banks, repeating the exercise as determinedly as children, and can mimic human responses as well as any parrot. But perhaps their most human quality is they mourn, and can even die from the loss of a mate. One hopes they lighten the darkness ahead for Shute because he has done them proud, ravenous or not.

Comments