The town’s first visitors were daytripping mill workers; now it’s a place for hen and stag parties. William Cook charts its changing fortunes, as a photographic exhibition reveals

Think of Blackpool and fine art probably isn’t the first thing that springs to mind, but Britain’s biggest, brashest seaside resort is the unlikely home to one of Britain’s loveliest little galleries. Hidden behind the grey seafront, a drunken stumble from the North Pier, the Grundy Art Gallery was founded in 1911 by two brothers — local philanthropists and art lovers — and this summer it celebrates its centenary with a photographic exhibition that spans the past 100 years.

No other town encapsulates Britain’s ups and downs quite as well as Blackpool. Its loud, lewd entertainments mirror the rise and fall of the British working class. It was never meant to be a regal spa, like Brighton: it was custom-built for the amusement of the lumpen proletariat. Its first punters were Victorian mill workers, the footsoldiers of the Industrial Revolution. By 1911, when the Grundy brothers built this splendid gallery, the British empire was at its peak and Blackpool was booming: the Tower, three piers, electric trams, and two million visitors every year. Of course most of these visitors were dirt poor, but what really strikes you about the photos of that era is how well they dressed.

Blackpool’s heyday was between the wars, and the Grundy gallery was flush with money. Every year its curators would travel down to London for the Royal Academy’s Summer Exhibition and buy a picture to bring home. They didn’t buy the latest thing. They just bought what they enjoyed. Rooting around in the gallery’s storeroom with the current curator, Stuart Tulloch, I’m amazed to see so many beautiful paintings by artists I’ve never heard of: romantic landscapes, whimsical portraits — utterly unfashionable, and all the better for it. They were already a bit old-fashioned in the Twenties and Thirties, when Blackpool bought them, but that’s what makes them so enchanting. They’re unsophisticated and unselfconscious, rather like the town itself.

These charming artworks get an airing now and then (I saw some of them on show here a few months ago) but the Grundy’s current exhibition has a far tougher edge. Curated by the German artist Nina Könnemann, it casts a cool, dispassionate eye over Blackpool, past and present.

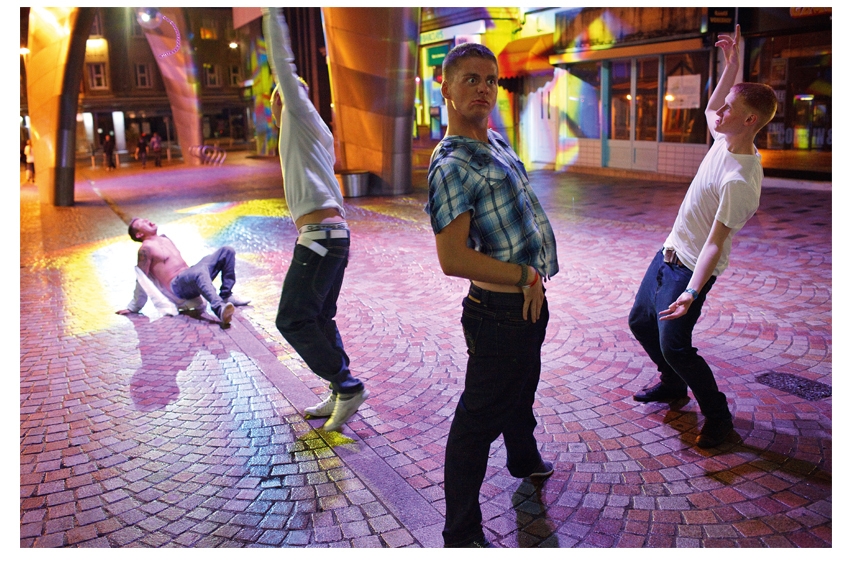

As this unsentimental show confirms, Lancashire’s answer to Las Vegas has always been a place to let your hair down — a Wild West town full of hucksters and fortune-tellers, rife with infidelity and fast food. People still come here to drink and fool about, but the bright, modern photos in this display feel more pessimistic than their faded predecessors. Even the camera angles are more intimidating. A woman eating chips looks close to tears. ‘Sex Appeal — Give Generously’ reads the band around her hat. Maybe it’s just nostalgia, a longing for lost youth, but the older photos seem more innocent and the people in them look happier. Even the old rides at the Pleasure Beach are more childlike than those today. In these 21st-century photos you can sense an unravelling of traditional values. The older revellers were probably just as drunk, but they were certainly more dapper.

Blackpool through the Camera features contemporary photographers such as Martin Parr, but the core of this show is the work of Humphrey Spender and Julian Trevelyan, who came to Blackpool in 1937. Spender and Trevelyan were participants in the Mass Observation project, which aimed to create a comprehensive record of ordinary people’s daily lives. Their snatched snapshots confirm that although today’s pleasure-seekers have swapped lounge suits for shellsuits, Blackpool has always been a garish place, awash with tattoo parlours and amusement arcades. ‘The Headless Woman — You Must See Her’ reads a billboard in one of these Thirties photos. ‘Baffling scientists and doctors.’ Blackpool was ever thus.

Yet the best show in town is the town itself — open all hours, admission free — and a short stroll from the Grundy brings you to Blackpool’s battered prom. With eight million visitors a year, this windswept stretch of concrete (seven miles long) is still Britain’s most popular attraction — more people visit the Illuminations than do the Edinburgh Festival. The council is busy patching up the promenade, laying fancy new pavements and diverting the seafront traffic, but Blackpool will never look neat and tidy. It was built on boom and bust.

‘Spend your summer holidays in Blackpool’ reads an old railway poster in the Grundy’s giftshop. ‘Everything in full swing.’ Blackpool is still in full swing, but not as many folk come here for their summer holidays nowadays. Blackpool’s first visitors were daytrippers — the resort was close enough for mill workers to travel here after church on Sunday morning (a sign of how much Blackpool — and Britain — has changed). When the mill owners finally agreed to give their workers proper holidays, people flocked here for a full week, en masse, one mill town at a time. The towns that fed this resort are still there, but the mills closed long ago, and cheap flights have given modern holidaymakers something Blackpool could never provide — guaranteed good weather. Now it’s mainly weekend traffic — some families, but a lot of stag and hen.

Variable weather was a key factor in the evolution of Blackpool’s finest artform, live Variety — punters were happy to pay for indoor entertainment to escape the wind and rain. Against all odds, a fragment of this great tradition has survived. Blackpool is the only seaside town that still has a proper summer season and though its glory days are long gone some of the old-timers are still clinging on, like boxers praying for the bell: Frank Carson at the Grand Theatre, Cannon & Ball on the North Pier. Yet you could have come here 30 years ago and seen the same acts, in the same theatres. Blackpool used to be the top ticket, final confirmation that you’d really made it.

Not any more. It’s a faint echo of the old days, when the summer season ran from April to October, and pantomime from November until Easter. Punters would come out of a show and book the same seats for the same night next year. The list of acts who played the Opera House reads like a timeline of light entertainment: Lillie Langtry, Charlie Chaplin, Arthur Askey, Morecambe & Wise. Once upon a time, you could see Tony Hancock here, and Harry Secombe, and Les Dawson. Today you have to make do with Roy Chubby Brown.

Yet like a decrepit old diva whose best days are behind her, Blackpool has survived — and she’s become more endearing in her dotage. Blackpool knows it’s a bit rubbish really, and that’s what makes it so appealing. There’s a rich vein of self-mockery in this town, and the mill towns that surround it. Maybe that’s why so many comics come from Lancashire. So what does the future hold for Blackpool? Can it reinvent itself as a cultural capital, like Brighton? Despite galleries like the Grundy, I doubt it. Blackpool is incapable of taking itself too seriously. It’s too self-deprecating for high art. The days when people would spend a fortnight here are gone for good, but Blackpool has too much vulgar joie de vivre to die away.

As I finished my fish and chips and headed for the station, the sun came out and I recalled the old catchphrase of Blackpool’s favourite comic, George Formby: ‘Turned out nice again.’

Mass Photography — Blackpool through the Camera is at the Grundy Art Gallery, Blackpool, until 5 November, admission free. For more information call 01253 478170 or visit

www.grundyartgallery.com

Comments