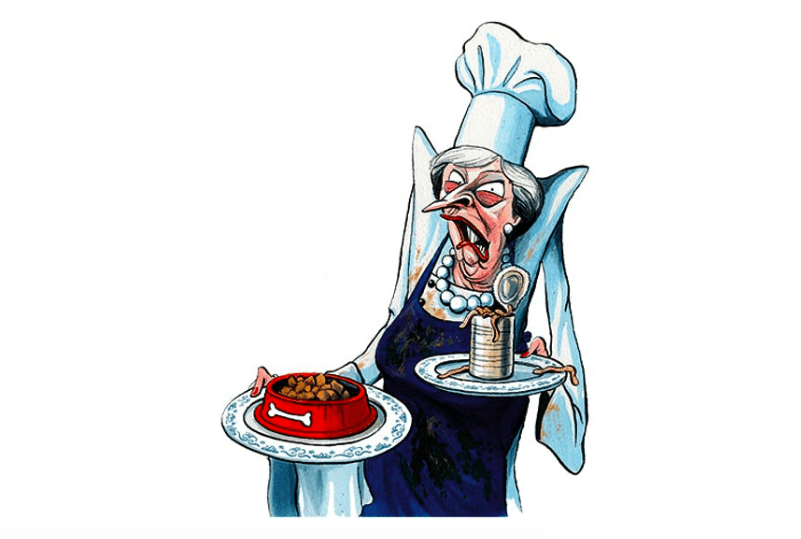

Are Remainers to blame for the looming hard Brexit? The theory goes that had Remainers compromised and accepted soft Brexit, none of what is about to unfold would ever happen. It’s true that the behaviour of some Remain campaigners in the aftermath of the referendum has hardly been exemplary. The whole Russian conspiracy thing was deeply alienating to anyone who might have listened to their case otherwise. These campaigners helped turned Brexit into a skirmish in the culture was, unconsciously saying that Brexiteers weren’t just wrong but a malign force in British politics. Some remain campaigners also sucked up to Corbyn in a fruitless and embarrassing manner. Yet hard Brexit isn’t their fault for a very simple reason: it is the fault of one person alone. That person is Theresa May.

Why? Because those who say that Remainers never got behind soft Brexit are ignoring reality. If you go back to late 2016, soft Brexit was the mode of the day for almost all leading Remain figures. Vince Cable, Chuka Umunna, you name it, all of them went on about Norway, leaving but staying in the single market, EEA membership. None of them talked about trying to reverse the 2016 result. The ‘People’s Vote’ campaign, which sought a second referendum, didn’t launch until April 2018; in the year leading up to that, we only saw a slow creep toward what would become familiar as the ultra-Remain position by activists.

What changed everything was Theresa May’s infamous Lancaster House speech in January 2017. This was where she announced that the UK would be leaving the single market and the customs union and that ‘no deal is better than a bad deal’. She said that Britain would be going for a very hard Brexit, in other words.

The effect of this speech cannot be understated; it radicalised both sides of the Brexit debate. Leavers, many of whom up until then were toying with the idea of how we could stay in the single market and yet have maximum national sovereignty, swung in behind hard Brexit fully. They had a prime minister who said she was going to go for a full-blooded Brexit, so any idea that a softer Brexit could or should be contemplated went out the window.

Remainers, seeing that not only was soft Brexit no longer available but that their pivot towards a Norway-style Brexit had possibly contributed to May’s speech, abandoned soft Brexit and searched for ways to reverse the referendum.

The worst thing about the Lancaster House speech, for all of its many historical faults, might well be that May didn’t mean a word of it. When push came to shove, she demonstrated that she was willing to do almost anything to avoid a hard Brexit, never mind flirting with no deal. She had said what she said in January 2017 to get the hard line Brexiteers on board, not realising that by doing so she was massively raising their expectations. She was, of course, setting herself up for a fall. The fact that she was the first victim of her Lancaster House speech should provide some schadenfreude; given everyone in the United Kingdom is going to feel the negative effects of her folly for years, if not decades, it feels appropriate.

But there is someone else who can share a portion of the blame for what will unfold over the coming weeks. And no, it’s not Boris Johnson but Jeremy Corbyn. Had he embraced soft Brexit the course of events would have been radically different. It would have given Remainers and those who actually wanted a Norway-style arrangement something to coalesce around. But it’s true that this would have been a political gamble for the Labour party. I am no fan of Corbyn, but the reality is that May’s 2017 speech had left little room for any outcome other than a very hard Brexit and, indeed, made no deal the most likely outcome. May’s speech made it very difficult for Corbyn to favour a softer form of Brexit. And for that, she must shoulder most of the blame for the situation we are in.

Now that Theresa May is no longer prime minister, everyone has become kinder towards her time in office. Those on the left have bigger, more immediate fish to fry in Boris Johnson; the right don’t tend to like to blemish their own more than absolutely necessary. This revisionism toward May’s premiership is false, though. More than anyone else, she is to blame for the current Brexit crisis, and any of the fallout which will hit Britain in the coming weeks.

Comments