Certain days in the long and sometimes glorious history of English cricket are so brightly coloured they can never fade. Two such are the 20th and 21st of July, 1981. Age and the passing of time cannot weary them. The old tape has been played and replayed so often, it becomes all but impossible to discern between the facts of the Headingley test that summer and the legend it has become. Sometimes the facts are legendary enough.

That was Botham’s match, of course, but also Bob Willis’s finest hour. Without Willis and his eight wickets for 43, Botham’s heroics, his 149 not out that gave England a sniff of victory they had no right to contemplate, would have been little more than a gallant act of defiance in a long-doomed cause. Botham gave England a chance; Willis took it.

Now Robert George Dylan Willis – he added the Dylan out of respect for Bob Zimmerman and, it was sometimes said, because three initials were better than two if you wanted to play for England – has died at the age of 70. It seems an all too sudden departure and a heavy one too.

That heroic performance at Headingley so over-shadowed the rest of Willis’s career it became easy to forget just how good a bowler he was. He took 325 test wickets at an average of 25 and if some of these were against Australian sides weakened by Packer defections it remains the case that no English fast bowler since Trueman and Statham has a better average than Willis. Indeed he was England’s greatest pure quick between the age of Trueman and the arrival of the Jimmy Anderson era.

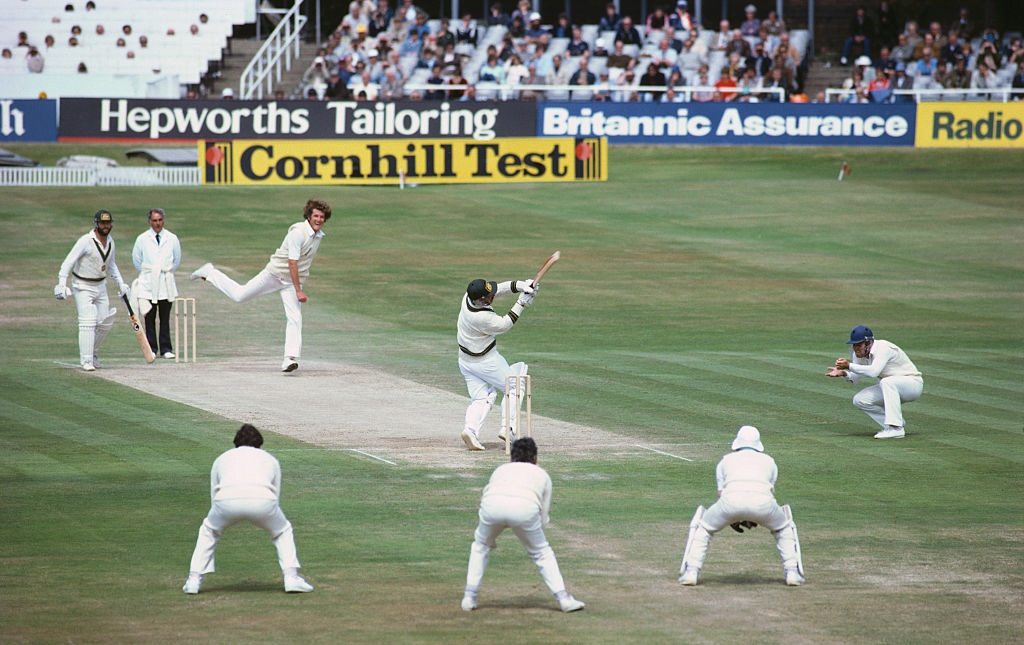

Pace, indeed, was Willis’s chief weapon. He was not a subtle bowler; bounce and hostility were his greatest attributes. Possessing, it seemed, an extravagant quantity or arms, knees, and elbows he tore in to the wicket off his long, long run, with a flailing intensity that resembled nothing quite so much as a dervish designed by Heath Robinson.

That afternoon at Headingley, with Australia needing just 130 to win was imperishable. Botham dismissed Graeme Wood to reduce the Australians to 13/1 but thereafter Trevor Chappell and John Dyson settled and with the score nudging past 50 it looked as though Botham’s heroics the previous day were likely to be in vain.

Enter Willis. Switching ends to bowl from the Kirkstall Lane end, he was given the instruction by Mike Brearley to “let it rip”. This was a moment for do-or-die, nothing-to-be-lost pure hostility. And, by gum, Willis delivered. Bowling short and fast and extracting murderous bounce from the fifth day pitch he had Chappell caught behind before removing Kim Hughes and Graham Yallop for ducks. Chris Old bowled Allan Border but every other wicket fell to Willis as England completed an extraordinary victory by 18 runs. At the end, the sight of Willis leaping for joy and careering across the Headingley turf, arms spread like some monstrous, wide-eyed, pterodactyl remains imperishable.

Watching Willis, too, was to be reminded that fast bowling is heavy work. He was never a particularly natural athlete, nor did he ever make it look easy. A succession of injuries, particularly to his knees, would have finished a lesser competitor. Willis often had a lugubrious air about him but then a fast bowler’s lot is not always a happy one. But, knackered knees or not, he invariably summoned the effort for one last spell before the close of play.

If he was not a particularly imaginative captain of England – for his turn came when Brearley retired – it was not for want of effort on his part. Indeed, he rarely bowled better than in the twilight of his career, taking 77 wickets at just 21 in his 18 tests as captain. Even so, he could be annoying; his captaincy style gave the impression Willis viewed spin-bowling as a suspicious waste of time, for instance.

Like so many England captains he later found a perch in the Sky commentary box, a position which did not entirely suit him. In later years, however, he moved to a more analytical role which proved very much more the ticket. Indeed, one of the consolations of an England calamity – of which there has never been any shortage – was the spectacle of Willis tearing into the team’s inadequacies.

He gave no quarter and often was right not to. Lurking behind the disparagement, you often felt, was a suspicion that some players valued wearing the England sweater rather less than Willis had himself. It helped that his nasal tones were the perfect conduit for disdain. But there was wit and warmth aplenty too and Willis had sufficient self-knowledge to enjoy teetering on the brink of self-parody without quite toppling over into it.

Graham Dilley was the first of the boys of Heaindgley 81 to leave the field; now Bob Willis joins him in departing all too soon. The memory of that day, however, lives on and will do so for as long as cricket is still played in England.

Comments