We have just witnessed one of the most dramatic defeats in the history of British by-elections. A 38 per cent swing against the governing party has happened only a handful of times in postwar politics and tends to be a sign of bad things to come. The last time the Tories lost a safe seat to the Lib Dems was Christchurch 1993, presaging the great Conservative collapse of 1997.

So losing North Shropshire is devastating for the Conservatives: they haven’t just lost a stronghold but have seen the all-but-dead Liberal Democrats take it with a huge majority. This happened because so many of voters there — one of the most pro-Brexit, pro-Tory parts of the world — wanted to make this into a referendum on the shortcomings of Boris Johnson’s government.

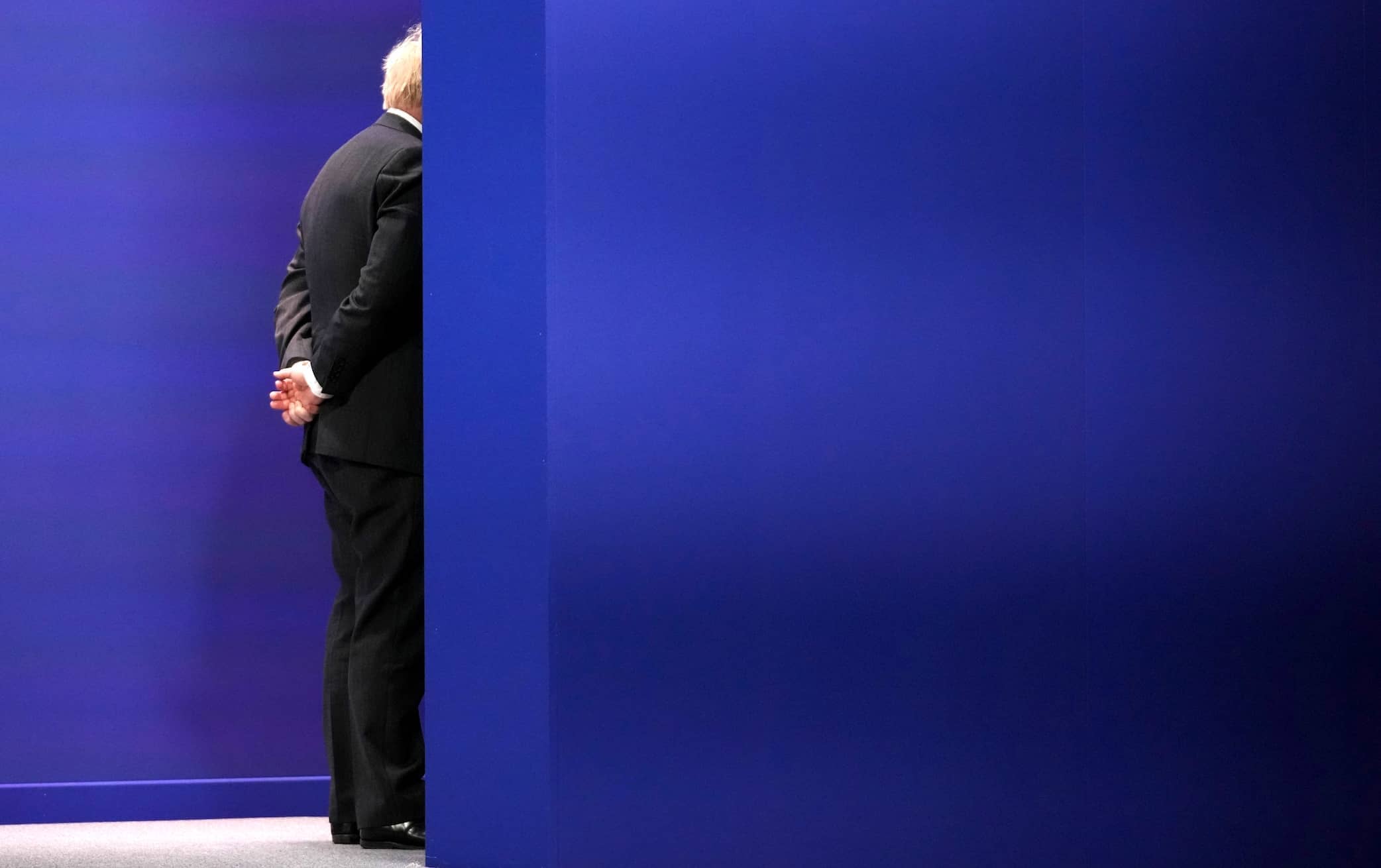

The strong arm has become his default tactic and it’s a sign of his weakness rather than strength

The vaccine passports vote was a calamity for Johnson and his relationship with his party, needlessly and perhaps irrevocably alienating his base. It was as bad a political misjudgement as the Owen Paterson debacle which led to this by-election in the first place. In my Daily Telegraph column today I argue that — with vaccine passports and more — he is becoming the kind of illiberal politician that he used to warn us about in his 20 years as a columnist and editor. His decision to push through these passports while being unable to publish any evidence that they work was quite a breach: not just with his party, but with the principles he stood for before being elected.

I find it hard to see how this damage can be repaired and very easy to see how it can be worsened. Popularity tends to go only one way for prime ministers (see below graph). As one Tory MP told me: ‘When Etonians die, they die quickly.’

Johnson has not just galvanised his enemies but (as James Forsyth argues in the Times today) alienated his base. This isn’t a freak but a series of mistakes traced back to dysfunction in No. 10. This by-election itself was a result of Johnson’s personal botched attempt to save the former MP Owen Paterson from a 30-day suspension for lobbying breaches: he did it so badly (and against the advice of his own staff) as to turn a Westminster embarrassment into a political disaster. So this defeat has his signature on it, just like the tax pledge he ordered his MPs to renege on a few weeks ago. The strong arm has become his default tactic and it’s a sign of his weakness rather than strength.

So will he have to walk the plank? Not yet. Many Tories might want him gone, but you don’t hear is anyone saying ‘Liz Truss is our only hope now’ or ‘Only Rishi Sunak can save the northern Tory seats’. The left-right coalition of Boris Johnson’s critics do not agree on what follows: MPs like Sir Roger Gale who hated Brexit and the likes of John Redwood who don’t think he has taken Brexit far enough. These gentlemen are unlikely to agree on who should follow Johnson. When Theresa May botched the 2017 election she was politically a dead woman walking. But the Tories kept her walking because they could not agree on who should replace her.

It’s not impossible that Johnson recovers — he has come through many scrapes, escaping death politically and (with Covid) physically. Many of those who backed him (including me) still hope that he might rediscover his principles: the leading article of our Christmas issue suggests he spends the holiday reading his old columns about liberty and wondering if old Boris might have had a point.

And yes, the Tories are Europe’s leading regicide specialists. But they do it strategically, not as an act of rage. So there can be a large interregnum between Tory MPs losing confidence in their leader and deciding that the moment is right for a leadership contest. We could well have entered that political purgatory, but it might last for some time.

Comments