There is chatter in the Westminster village about Boris Johnson’s low-profile. Why isn’t he visiting flooded towns? Why isn’t he fronting efforts to reassure a country worried about pandemic coronavirus?

Here, I think it is worth quoting at length a speech given before becoming prime minister:

‘If we win the election we will get our heads down and get on with implementing the big changes I’ve spoken about today. You will not see endless relaunches, initiatives, summits – politics and government as some demented branch of the entertainment industry. You will see a government that understands that there are times it needs to shut up, leave people alone and get on with the job it was elected to do. Quiet effectiveness: that is the style of government to which I aspire. And I also know that because we believe in trusting people, sharing responsibility, redistributing power: things will go wrong. There will be failures. But we will not turn that fact of life into the tragedy of Labour’s risk-obsessed political culture where politicians never say or do anything that really matters, or really changes anything, for fear of getting some bad headlines. If we do these things that I have said, I believe we will be able to bring about the change the country needs.’

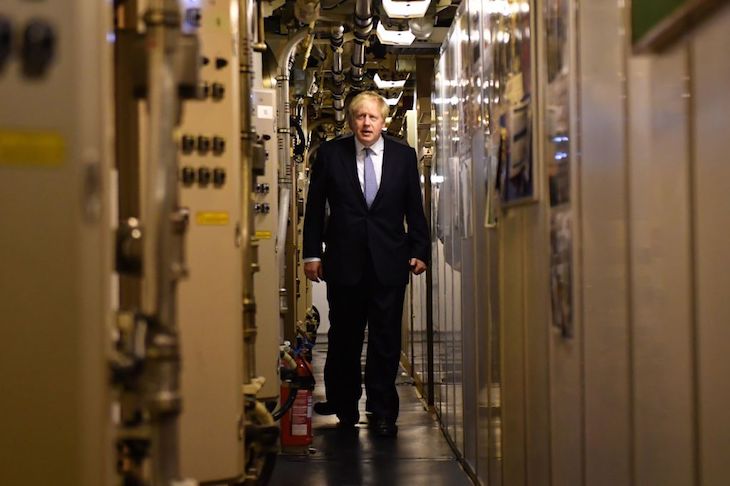

That, I think, is a pretty good summary of the thinking that underpins Boris Johnson’s submarine strategy.

It’s also, to my mind, very sensible. I spent over a decade of my working life as a political reporter covering the day-to-day ‘news’ from Westminster: the relaunches, initiatives, summits and – above all – the announcements. Oh, God, the announcements. I’d hate to know what proportion of my time as a Lobby correspondent was spent writing about politicians announcing they would do something. I guarantee it was far more time than I spent writing about whether they actually did that thing, or what actually happened to the services, people and places who were supposed to be affected by that thing.

Throughout my time as a reporter, I was troubled by the realisation that a lot of the things I was writing about didn’t really matter, at least not to most people. The vast majority of people in the UK are not remotely interested in a Cabinet minister they’ve never heard of, promising to do something or other. Nor does it matter much to them whether the Prime Minister is on the telly every night, showing he feels their pain or knows how much a pint of milk costs.

Promising to be a PM who stays out of the headlines, letting others get on with their jobs can be easy. Actually doing it is hard.

Since this is an age of Lobby-bashing, I should make clear that nothing I say here is to denigrate the importance of political journalism – quite the contrary. I still believe it is a vital part of the trade and that the Lobby do good work on one of the fundamental requirements of journalism in a democracy: keeping politicians honest. They do that simply by reporting the things politicians say, so voters can judge for themselves how the actions of politicians measure up to the things they say.

However, journalism can be essential without being sufficient. It has now been nearly six years since I ceased being a political editor and stopped reporting politics day-to-day, and three since I gave up my Lobby pass. The perspective distance brings persuades me that Lobby reporting is still vitally important, but journalism as whole needs to do an awful lot more than report on ministers announcing stuff, and politicians and their aides saying catty things about one another. In newspaper terms, I wish there were more specialists and more regional correspondents.

All of this brings me, sort of, back to Boris Johnson’s low-vis strategy and Downing Street’s disdain for my former Lobby colleagues. This may not make me popular among those former colleagues, but I think the strategy is perfectly sensible, even if the manner of the disdain can be unnecessarily discourteous. I don’t think the Government or the Conservative Party’s chances of re-election will be much changed by Boris Johnson’s failure to make appearances in daily media coverage.

But my real point here is not to assess that strategy’s wisdom, it’s to put it in context.

Look again at the above quote before election, a promise not to govern by announcement and treat ‘government as some demented branch of the entertainment industry.’

Those are not Boris Johnson’s words, they’re David Cameron’s from a speech made almost exactly a decade ago in February 2010.

Did Dave live up to that promise, did he avoid government by announcement and resist the temptation to comment on every passing media tizz? Having reported on the Cameron premiership, I think it’s fair to say he didn’t entirely keep the (laudable) promises made in that speech.

The reasons why are important to assess whether Boris will succeed where Dave failed.

Promising to be a PM who stays out of the headlines, letting others get on with their jobs can be easy. Actually doing it is hard. That’s partly because, when the people you’ve empowered to get on with those jobs screw up (and they will, because people are people), you’re the one who gets the blame. Maybe it would be good to reverse the premiership’s presidentialization; go back to the PM as primus inter pares at Cabinet, but it’s not going to happen. So the buck will stop with Boris as it did with Dave, Gordon and Tony.

One of the reasons for this failure to step back is psychology: the sort of person who becomes PM is neither shy nor humble, so naturally they want to be seen as the man in charge, the guy who fixes and delivers.

Some of the failure is down to the experience of being PM. It’s a funny thing, ‘running the country’ from a townhouse in central London. You get information about the country you run from intermediaries and proxies, second-hand reports and data. Almost inevitably, you’re prone to tunnel vision, thinking daily media reporting is more important than it is; it doesn’t help when you’re surrounded by colleagues fixated on day-to-day or even hour-to-hour drama.

Will Boris Johnson be able to maintain the low-vis strategy as his honeymoon period with colleagues fades and his government runs into inevitable crises? History suggests we should bet against him.

On the other hand, there are a couple of differences with this Prime Minister. Boris Johnson is still, at heart, a journalist. He knows what matters about journalism, and what doesn’t. (It’s a navel-gazing distinction but he’s a columnist, not a reporter, and good columnists have healthy disregard for daily reporting).

There’s also an intriguing question of character here. Since the general election campaign, Johnson has shown a level of person discipline, a commitment to being boringly on-message, which has surprised many who have worked with him over the years. He really wants this job, wants to keep it, and is prepared to stick to the plan he believes will deliver that.

And the media has changed too. The papers that used to shake No.10 to its foundations are smaller and less fearsome. The beast still demands to be fed, but its calls are easier to resist than they once were. In Tennyson’s phrase:

‘We are not now that strength which in old daysMoved earth and heaven, that which we are, we are’.

I still have doubts that Submarine Boris will stay submerged for the duration of what could be a long premiership. But I think he’ll surface less often than his recent predecessors, and benefit from that too.

Comments