This country will end the Brexit transition period with a zero tariff, zero quota deal with the EU. Four and a half years after the Brexit vote, the issue that has so convulsed British politics is settled.

We are still awaiting the text of the deal. But from what both sides have said it is clear that this is a pretty full fat Brexit: Britain leaves the single market and the customs union and there’ll be no dynamic alignment with EU rules in the future.

On the three key tests of money, borders and laws – it looks like the deal passes

The two sides will be able to put tariffs on each other if they feel that they have raised their standards and the others refusal to follow suit puts them at a trading disadvantage. But crucially this power is reciprocal, subject to independent – not ECJ – arbitration and has to be proportionate: the EU couldn’t slap tariffs on a host of British goods over some very minor difference. In his press conference, Boris Johnson suggested that if Britain increased its animal welfare standards – banning sow stalls for instance – and the EU didn’t do the same, it might consider putting tariffs on EU bacon to adjust for that.

Taking questions from the media, Johnson effectively conceded that the area where the UK had given the most ground in these negotiations is fishing. There will be a five and a half year transition and Ursula von der Leyen spoke in her press conference of how the EU has ‘strong tools to incentivise’ the UK to continue offering access to the European fishing fleet after that.

But on the three key tests of money, borders and laws – it looks like the deal passes. Indeed, even the Brexit/Reform party appears to be backing the deal and Nigel Farage gave it a qualified welcome earlier.

One striking feature of Johnson’s press conference was the tone he struck, talking about the ways in which the EU is a ‘noble enterprise’ and how Britain would always be a culturally European country. It suggested that outside of the EU, the UK could have a more constructive relationship with it. Indeed, the problem ever since Britain joined the European Economic Community in 1973 was that this country didn’t really want an ‘ever closer union’, which always made us an awkward member of an organisation whose stated goal was that. It is also why Brexit was, to my mind, always a question of when rather than if. Ultimately, the EU is heading to a level of political and fiscal integration – as illustrated by the ‘Hamiltonian moment’ of the Covid recovery fund – that few in Britain want to go to.

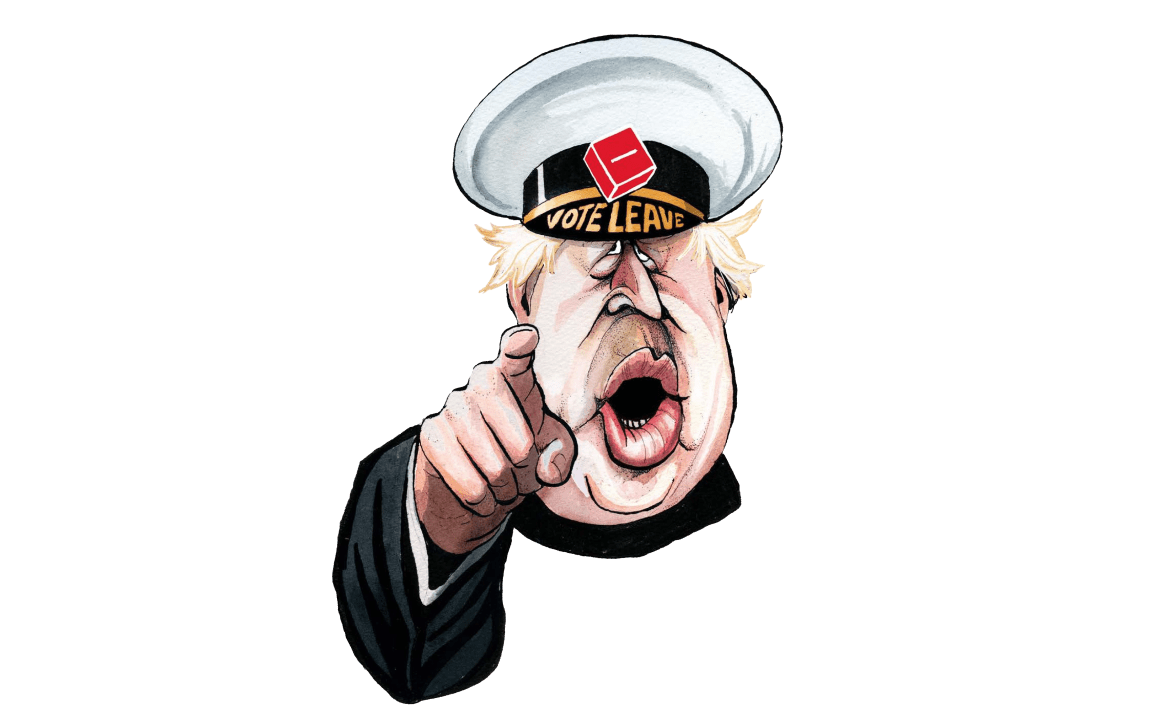

When Johnson resigned as Foreign Secretary in July 2018 over Theresa May’s Chequers proposal, he was gambling that another form of Brexit was possible to the one that the then Prime Minister was proposing: one that would see the UK accept more friction at the borders in exchange for far greater regulatory freedom. Today, after a leadership contest and a general election, he can say that he achieved that.

But the really hard work starts now. Ever since the referendum, Brexit has been a process story about negotiations and missed deadlines. Now this country must show what the point of it is: what it intends to do with the powers that it has brought back. Can this government put flesh on the bones of its idea of a nimble, global Britain that can gain an advantage in the industries of the future by having its own regulatory frameworks? That is now the challenge facing Boris Johnson.

Comments