This week, Nick Clegg added his name to the fast-growing list of politicians addressing

the critical question of living standards. His phrase of choice was ‘alarm clock Britain’, in effect his version of Ed Miliband’s ‘squeezed middle’. It is, of course,

a clunking label for what is a serious topic (hardly the first time a politician has achieved such a feat). But quibbles over terminology aside – and as Miliband’s article on Friday confirmed – these are the first serious shots in the political

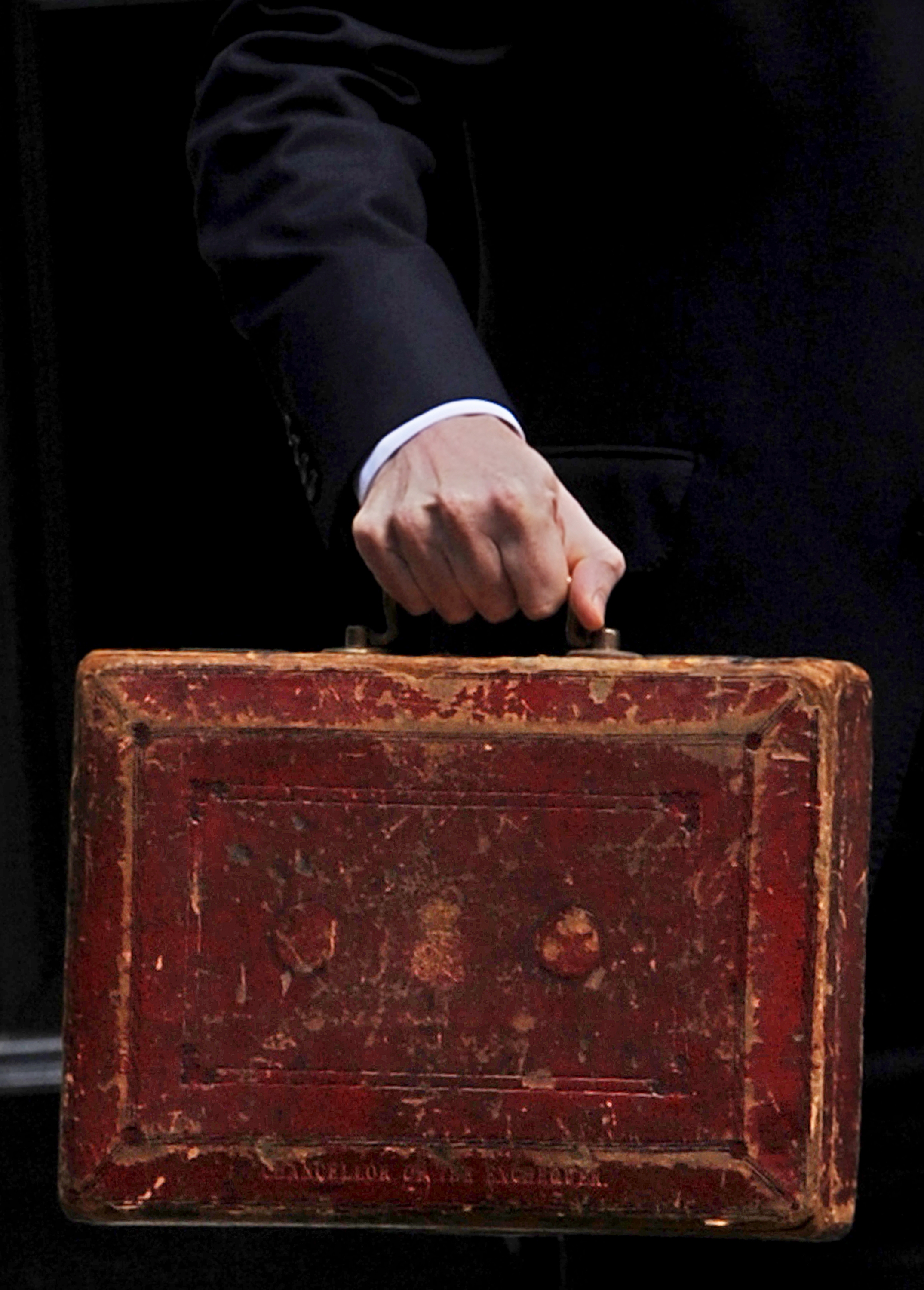

battle to frame the coalition’s crucial March Budget.

This week, Nick Clegg added his name to the fast-growing list of politicians addressing

the critical question of living standards. His phrase of choice was ‘alarm clock Britain’, in effect his version of Ed Miliband’s ‘squeezed middle’. It is, of course,

a clunking label for what is a serious topic (hardly the first time a politician has achieved such a feat). But quibbles over terminology aside – and as Miliband’s article on Friday confirmed – these are the first serious shots in the political

battle to frame the coalition’s crucial March Budget.

It is now increasingly clear that at the heart of that struggle will be attempts by party leaders to court working households – particularly families with children – on low-to middle incomes. In that battle, Clegg has now given the strongest indication yet that the coalition’s leading argument will be a £10,000 personal allowance (at a cost – as yet unfunded – of around £10bn). The most obvious implications of that move have already been quite widely discussed. When looked at in isolation, it will be welcome news for basic rate taxpayers – and welcome relief from the current squeeze of flat wages and higher inflation. But when set against the coalition’s wider plans, the upsides will struggle to be noticed. In the next year alone, many of the same people to benefit from the higher allowance will – amongst other things – lose the family and baby elements of the Child Tax Credit (over £500 each); see cuts to childcare support (an average of nearly £500); and suffer the abolition of EMAs (as much as £1,000). The VAT increase alone will hit low-to-middle income families by upwards of £200, more than offsetting this year’s gains from the raised allowance.

When it comes to the distributional impact of the change, too, the jury has already returned a verdict: the answer rests largely on how the move is paid for. In itself, the impact of a rise in allowances is “regressive” – as the IFS has shown – and if funded by cuts to key services or welfare, it is even more so. That said, the Lib Dems’ original plan of funding the policy through taxes at the top could have made for an overall progressive package. That will all come as little surprise.

But two other implications of the coalition’s tax strategy have as yet gone almost totally unnoticed. First, the government has made clear that it wants to target the benefits from an increased personal allowance at basic rate taxpayers. Assuming they continue with this approach, each further increase in allowances will need to be accompanied by a further lowering of the threshold for higher rate tax, dragging more people into the 40p rate (to offset any gains for higher rate taxpayers). April marks the first step of that journey: as allowances rise by £1,000, the starting point for higher rate tax will fall from £43,875 to £42,475. That will create 700,000 new higher rate taxpayers. And as the below chart shows, the threshold will have to fall much further if Clegg is to reach his goal of a £10k allowance:

The importance of this becomes clear when you draw the link to the Coalition’s plans for Child Benefit, and its proposed withdrawal from any households that pays 40p tax. Put the two policies together, and it’s clear that each time the personal allowance is increased – and the income threshold for the higher rate therefore falls – more and more of today’s basic rate taxpayers will find themselves shunted into the 40p tax band, and, as a consequence, will lose their Child Benefit. That means big cash losses – of around £1,700 for a family with two kids. The precise number of families facing this hit will depend on wage growth over the next few years, but one thing is clear: none of them see this coming.

The second major Budget surprise concerns reforms to employee’s National Insurance contributions. In April, the Coalition will go ahead with plans to raise to the basic employee NICs rate from 11 per cent to 12 per cent, and the ‘additional’ rate from 1 per cent to 2 per cent. Less well-known is the fact that the income level at which NICs start to be paid will rise significantly (from £110 to £139 a week), whilst the boundary line for paying top-rate NICs will be lowered (from £844 a week to £817).

So what’s the overall effect? Well, someone on £60k will be around £220 worse off, whilst someone on £10k will be around £140 up. But the NICs changes will also hurt many basic rate tax-payers. Above around £25k there will be losers from the changes, wiping most of the gain of the personal allowance for many basic rate taxpayers.

Why has there been so little discussion in Westminster of these important reforms? NICs are perhaps the least well understood part of the tax system; these changes are fiddly and most won’t have followed them. But a cynic might also note that silence on NICs is suspiciously convenient for party leaders. At a time of falling living standards, David Cameron is very unlikely to want to draw attention to yet another tax rise so soon after VAT (particularly since many commentators still incorrectly believe that the VAT increase is an alternative to any hike in NICs). Nick Clegg won’t want NICs to muddy the clear waters of his message that the Coalition’s tax plans help all basic rate tax-payers. And Ed Miliband, of course, has his own travails on the issue – most obviously the recent oversight from Alan Johnson on NI rates, and the fact that the public still associate Labour strongly with the NICs increase. Nor will the Labour leadership be keen to draw attention to the fact that, on NICs at least, the coalition’s changes help the low-paid.

For now, it all means a curious absence of public debate about big tax changes that are just around the corner.

James Plunkett is a Research and Policy Analyst for the Resolution Foundation. Gavin Kelly is Chief Executive of the Resolution Foundation.

Comments