I’ve made a short film with my friend Roger Bowles about why I’ll be voting Leave on 23 June and why I think you should, too. We’ve focused exclusively on the sovereignty argument, which we think is the most persuasive one. If you’re on the same side as us, please share this with as many people as possible.

We’ve called it ‘Brexit: Facts Not Fear’ because we think it’s important that people should be acquainted with as many facts as possible when they cast their vote. Below is a transcript of the film, with links corroborating the facts referred to.

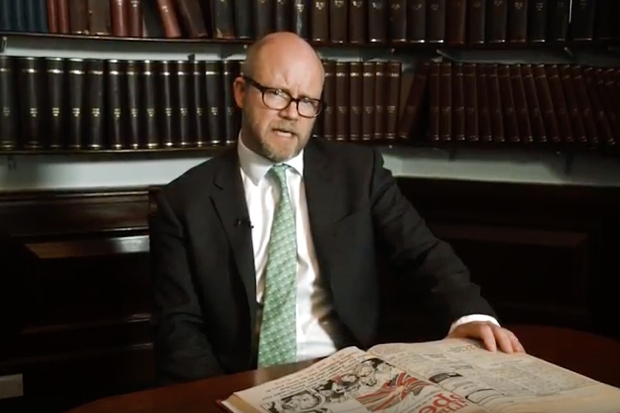

Hi. I’m Toby Young, I’m an associate editor of the Spectator. The British public have been crying out for facts in the Brexit debate so they can make an informed choice about whether to leave or remain in the European Union. So I want to give you some facts about what’s happened to British sovereignty since we joined what was then called the European Economic Community in 1973.

Fraser Nelson and Nick Cohen discuss The Spectator’s decision to back Brexit:

This room is where we keep the Spectator’s archives dating back to 1828 and I recently helped put together an anthology of material than appeared in the magazine in the run up to the first European referendum in 1975. The Spectator was one of only two publications to campaign for a Leave vote at the time, the other being the Morning Star.

In the official government pamphlet urging us to vote ‘Yes’ in 1975, the British people were given a guarantee that no law could be imposed on them without the consent of their elected representatives. ‘No important new policy can be decided in Brussels or anywhere else without the consent of a British Minister answerable to a British Government and British Parliament… The Minister representing Britain can veto any proposal for a new law or new tax if he considers it to be against British interests.’ That ‘veto’ turned out to be a figment of the government’s imagination.

Even back in 1973 when we first joined the EEC we didn’t have a veto over every new law proposed in Brussels. Some laws required a unanimous vote of the Council of the European Union, meaning any member state could veto them. Others could be passed by a majority vote. The 1975 government pamphlet urging us to vote ‘Yes’ tried to gloss over this inconvenient fact by using the weasel word ‘important’ – ‘No important new policy can be decided in Brussels’. But each time more countries join the European Union and another treaty is passed – each one bringing us closer to a United States of Europe – the number of laws deemed ‘important’ enough to require a unanimous vote gets smaller and smaller.

For instance, before the Treaty of Lisbon was passed in 2007, each member state had a veto over the EU’s common defence policy. Today, that can be decided by a majority vote. As a result of the Treaty of Lisbon, Britain lost its veto in over 40 policy areas. Defenders of the EU will tell you that Britain can still block EU laws, even if we can no longer veto them. Surely, if we oppose a particular measure, we can assemble a coalition of like-minded countries to join with us to defeat it?

In fact, finding other European countries willing to ally themselves with Britain has proved difficult. In the past 20 years, there have been 72 occasions when Britain has opposed a particular measure on the Council of the European Union. On all 72 occasions, we have been outvoted by the other member states. When it comes to the sovereignty of the British Parliament, the 1975 government pamphlet got it back to front.

While Britain can’t veto all new laws or new taxes made by the European Union, the European Union can veto laws and taxes made in Britain. For instance, in 1983 the European Court of Justice in Luxembourg ruled that the UK’s low duty on beer, as proposed by Nigel Lawson in his 1981 budget, was contrary to Article 95, paragraph two, of the Treaty of Rome. The British government had no choice but to put up the price of beer. No wonder the former Conservative Chancellor now believes Britain would be better off outside the EU.

This is one of countless times the British government has been overruled by the European Court. Just last year, the Court prevented the government from following through on its plan to freeze VAT on energy saving equipment at five per cent. Since 1973, the UK has lost 101 cases in the European Court and won only 30. That’s a failure rate of 77%.

Okay, say the defenders of the EU. But only a tiny percentage of Britain’s laws are made in Brussels. According to David Cameron, only 14%. Nick Clegg puts the figure at 7%. In fact, the percentage of Britain’s laws made in Brussels is 59%. That’s right, 59%. Don’t take my word for it. That was the conclusion of Jeremy Paxman in a recent BBC documentary. So for every five new laws imposed on the British people, three originate in Brussels.

And who makes these laws? If they were made by the European Parliament, in much the same way that our laws used to be made by our Parliament, that would at least give us some say, even if the British people only elect 73 out of a total of 751 MEPs.

But EU laws aren’t made by the European Parliament. Nor are they made by the Council of the European Union. In the EU, laws are made by a select group of 28 officials known as the European Commissioners. Did the people of Europe elect these eurocrats? No. Can the people of Europe kick them out if they do a bad job? No.

All 28 of them are political appointees – cronies of Europe’s political elite. European Commissioners aren’t just un-elected; in many cases, they’re people who’ve just lost elections. In Britain’s case, one of our best-known commissioners – Neil Kinnock – was appointed after the party he led had been rejected not once, but twice by the British electorate. This isn’t merely un-democratic; that’s anti-democratic.

Once laws have been proposed by these un-elected officials, the European Parliament, like the Council of the European Union, can only reject, amend or ratify them and, once passed, there’s literally no mechanism to repeal them. It’s not a proper Parliament at all. It has even less power than the House of Lords. There is simply no way the people of Europe can force their representative to get rid of a bad law.

Today, the government is telling us exactly the same stories it told us in 1975. In the pro-EU leaflet produced at a cost of £9 million to the British taxpayer, the government claimed that Britain had a ‘special status’ in the EU and that our continuing membership would preserve our role as a ‘leading force in the world’. ‘Our EU membership magnifies the UK’s ability to get its way on the issues it cares about.’

Again and again, we’re told by the Remainers that if we stay in the European Union, we can lead the European Union. But how can one country lead an organization when it can be outvoted in by 27 votes to one? Remember, on the 72 occasions Britain has opposed new EU laws and regulations it’s been defeated 72 times. Is that leading? In the European Court of Justice, we’ve lost 101 times and won only 30 times. That’s a failure rate of 77%.

Since David Cameron became Prime Minister, we’ve lost 80% of the cases we’ve brought before the ECJ. Is that leading? And if we vote to Remain in the EU, we’ll have even less influence than we do now. Earlier this year, the Prime Minister claimed he been able to secure a red card for Britain as part of his renegotiation. If you think that means a veto, think again.

By ‘red card’, Cameron doesn’t mean the UK will be able to unilaterally veto any more EU laws than it can at present. No, under this new proposal we can only object to a piece of EU legislation if we can persuade the national parliaments of 14 other member states to object to it as well. And we’d only have a few weeks to assemble this coalition.

Just how effective is this ‘red card’ likely to be?

Here’s William Hague, ex-Foreign Secretary, dismissing this proposal as laughable when it was first made in 2008: ‘…even if the European Commission proposed the slaughter of the first-born it would be difficult to achieve such a remarkable conjunction of parliamentary votes.’

Not only is this ‘red card’ useless, but in order to win this ‘concession’ Cameron had to surrender one of Britain’s few remaining veto powers – the right to give or withhold our consent to future EU treaties that convert the Eurozone bloc into a European superstate.

At present, 19 of the 28 member states are members of the Eurozone, with an additional seven due to join shortly. That will leave just Britain and Denmark outside the Eurozone. By surrendering our right to veto any further integration of this political bloc, we have given up our strongest bargaining chip in any stand off with the other member states. We will have no choice but to swallow all new laws or regulations that this political bloc comes up with, however detrimental they are to Britain’s interests. That was the conclusion of Peter Lilley, a former Secretary of State for Trade and Industry: ‘The UK would be very vulnerable if we remain in the EU on these terms.’

If the UK has enjoyed any influence within the EU it is because of the risk that we might one day leave. The other 27 member states may not have much love for Britain, but because we’re their largest single export market and because we’re the EU’s second largest net contributor – on average, we contribute about £10 billion a year to the EU’s annual budget – they’d prefer us to stick around. That’s why successive British Prime Ministers have been able to negotiate various rebates and opt-outs.

But if we vote to Remain, particularly after Cameron has surrendered one of our few remaining vetoes, Britain’s influence will ebb away to nothing. Any talk of leaving in future will be dismissed as an empty threat. The British people will have demonstrated their willingness to accept membership of the EU on any terms.

Henceforth, our acquiescence to whatever new laws and regulations the EU comes up with will be taken for granted. We fought a civil war in this country to establish the principle that laws should not be made nor taxes raised except by our elected representatives – no taxation without representation. Being able to get rid of our lawmakers is a fundamental democratic right. Why have we sacrificed that right in order to tether ourselves to a bureaucratic leviathan?

The Remainers will tell you that Britain would struggle to survive outside the EU — that we’d become an irrelevance. They call the people who want to leave the EU ‘little Englanders’, as if there’s something petty and small-minded about wanting Britain to become a sovereign state again. In their eyes, wanting to restore the right of self-determination to the British people is a bit… well, a bit common.

And this gets to the heart of the difference between their vision of Britain and ours. They see Britain as a small island off the coast of continental Europe that no longer has any place in the world as an independent nation state. We should abandon our delusions of grandeur and accept our diminished status.

We see Britain a little differently. Not just a small island, but the world’s fifth largest economy and fourth largest military power. One of only five countries with a permanent seat on the UN Security Council. Not the plaything of unelected officials in Brussels, but the birthplace of Parliamentary democracy.

If you believe that Britain is strong enough to stand on its own two feet again, free from the shackles of EU laws and regulations, then I urge you to vote Leave on 23 June.

The British people were fooled once in 1975. Don’t let the Establishment fool you again. It’s time to take back our democratic rights. ‘Men fight for liberty and win it with hard knocks. Their children, brought up easy, let it slip away again, poor fools. And their grandchildren are once more slaves.’ – DH Lawrence

| Will Britain vote to leave the EU? Can the Tories survive the aftermath? Join James Forsyth, Isabel Hardman and Fraser Nelson to discuss at a subscriber-only event at the Royal Institution, Mayfair, on Monday 20 June. Tickets are on sale now. Not a subscriber? Click here to join us, from just £1 a week. |

Comments