In the 1920s the linocut broke out of the schoolroom and on to gallery walls. Here was a democratic new art form, perfect for the times with its lowly materials — a piece of old linoleum flooring for the block, while the best tools, according to the artist Claude Flight, were an old umbrella spoke for cutting and a toothbrush to rub the back of the paper. The finished prints, Flight hoped, would be cheap enough for working-class pockets.

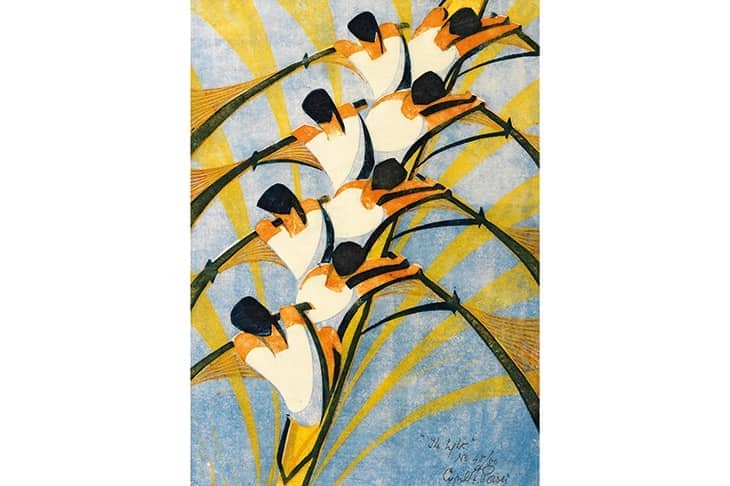

Above all, the bright, dynamic images themselves, often depicting scenes of contemporary life — busy streets, the London Underground, skating, the first motor races — captured the mood of the age. Influenced by the Futurists, the style was thrillingly modern, with its subjects simplified to near abstraction and its focus on speed, rhythm and pattern. Jenny Uglow’s excellent, vividly illustrated new book tells the story of two of the most talented practitioners of the art, Cyril Power and Sybil Andrews.

Cyril was an architect in his late forties when he met the 21-year-old Sybil. Within a year he had left his wife and four children to begin their two-decade-long artistic collaboration. They shared a studio and a diary, wrote and exhibited together, printed each other’s designs and sometimes even developed each other’s preliminary sketches. This impressive lack of artistic ego speaks of love; and indeed Uglow convincingly argues that theirs was far more than a professional partnership. The pair spent almost every moment together, taking equal delight in music, theatre and medieval history. While Sybil made jam and iced Christmas cakes, Cyril (known as ‘JM’ — Jest Master) played his growing collection of instruments and wrote jokey poems to commemorate their feasts.

They shared a studio, a diary and each other’s designs, and the impressive lack of ego speaks of love

One of their concerns was to define this new art of linocuts. In the mid-1920s they produced a manifesto (it was a time when you could hardly call yourself an artist without one), Aims of the Art of Today, each initialing their contributions. Drawing on the ideas of Roger Fry and Quentin Bell, they declared that their purpose was to simplify, to show the ‘essence’ of a subject and to capture an almost musical sense of movement and pattern. Above all, they said, echoing Kandinsky: ‘We are “out” now to try and express the big things behind outward visible facts — The Eternal Spiritual Reality behind material things.’

Power’s images of modern life often achieve a complex emotional atmosphere that may hint at this spiritual reality. ‘The Escalator’ (1929), which shows a figure looking (fearfully? With determination, or relief?) up a vast escalator to the light beyond, and ‘Whence and Whither’ (1930), again showing an escalator, this time crammed with faceless lines of people descending into the abyss, are among many that portray the technological world ambiguously.

Uglow makes the point that it was not until the end of the 1920s that many of the best-known books about the first world war, such as All Quiet on the Western Front, Goodbye to All That and

A Farewell to Arms, were published: ‘It seemed that ten years had to pass before writers could begin to face the horror of war.’ This, as well as Power’s personal circumstances — he was a Catholic, who had abandoned his family after all — appear to underlie the deceptive simplicity of his art.

Andrews’s work, by contrast, vibrates with effort and vigour. A horror of prettiness pushes her figures towards the angular and muscular. Subjects that in other hands might be picturesque, such as flower-sellers, are about their labour with their heavy baskets. She delights both in the rhythms of industry — the winding of huge winches and the wielding of sledge-hammers — as well as traditional rural scenes, such as shire horses at work in the fields. She would later tell her students to ‘put it down violently, as violently as you can. Your violence will be used positively.’

If the mass market for linocuts that the couple had hoped for never quite emerged, Sybil at least spoke to a mass audience through posters for the London Underground. Cyril was originally given the commission, but then became busy at the RIBA, leaving Sybil to do the work alone. Advertising sporting events, her crisp, exciting graphics were the first examples of modern art that many London Transport passengers came across. They were signed ‘Andrew-Power’, which Sybil regretted, calling it ‘a mess up’. Uglow writes:

Her crossness suggests that, despite their closeness, collaboration was not always to her advantage. Like most women artists of the time she was made to feel overshadowed, marginal — however close the partnership, the balance of power lay with the man.

One can sense, as time passed, the power shifting in their relationship. Cyril began as Sybil’s teacher (she said of their early friendship: ‘To me it was like a university course, Art Architecture History Archaeology Music’). But it was her energy and enthusiasm which came to support her more diffident partner. Years later she insisted that ‘he followed me [to London], not the other way about’, and furiously denied that their relationship had ever been sexual. It was simply a matter of convenience, she claimed — he couldn’t afford a studio, so shared hers. Uglow treads delicately here, noting that while their friends and families assumed they were lovers at the time, ‘who can deny [Andrews] the right to possess the facts of her own life?’ Yet one can’t help feeling her remarks are reductive —unworthy of her.

In 1943 the partnership ended when Sybil met and married (swiftly, as she did everything) a man called Walter Morgan. Cyril quoted Catullus in his sketchbook: ‘I hate. I love…’ He put away his lino blocks forever, returned to his wife and family (who seem to have had him back without a murmur) and died seven years later.

Sybil, meanwhile, moved with her husband to Canada, where she worked as an artist until her death in 1992. She lived to see the revival of interest in her linocuts, and to write warmly of Cyril to his son. But Uglow wistfully imagines the bonfire that consumed all Cyril and Sybil’s letters to each other at some point after their relationship finished: ‘Scorched pages fluttering and curling, handwriting vanishing into air.’ She demonstrates here her skill at conjuring up lives in time and her light touch in assembling images and ideas from contemporary culture. But it’s a shame that some boring, conventional demon has robbed us of what surely once existed: direct words of love between these two fine artists.

Comments