More Indians? Bring them on. The more the better. The prospect of a forthcoming tidal wave of immigration following Labour striking a trade deal with India is the best news in years.

The last tidal wave of Indians arrived from Uganda and they were a shot in the arm of moribund Britain – where because of half-day closing, you couldn’t even buy a pint of milk on a Wednesday afternoon.

That changed after August 1972 when Ugandan dictator Idi Amin ordered the expulsion of approximately 80,000 South Asians (primarily of Indian descent) from Uganda, giving them 90 days to get out and changing Britain massively for the better, not least because they taught a nation of shopkeepers how to keep shop.

The prospect of a forthcoming tidal wave of immigration following Labour striking a trade deal with India is the best news in years

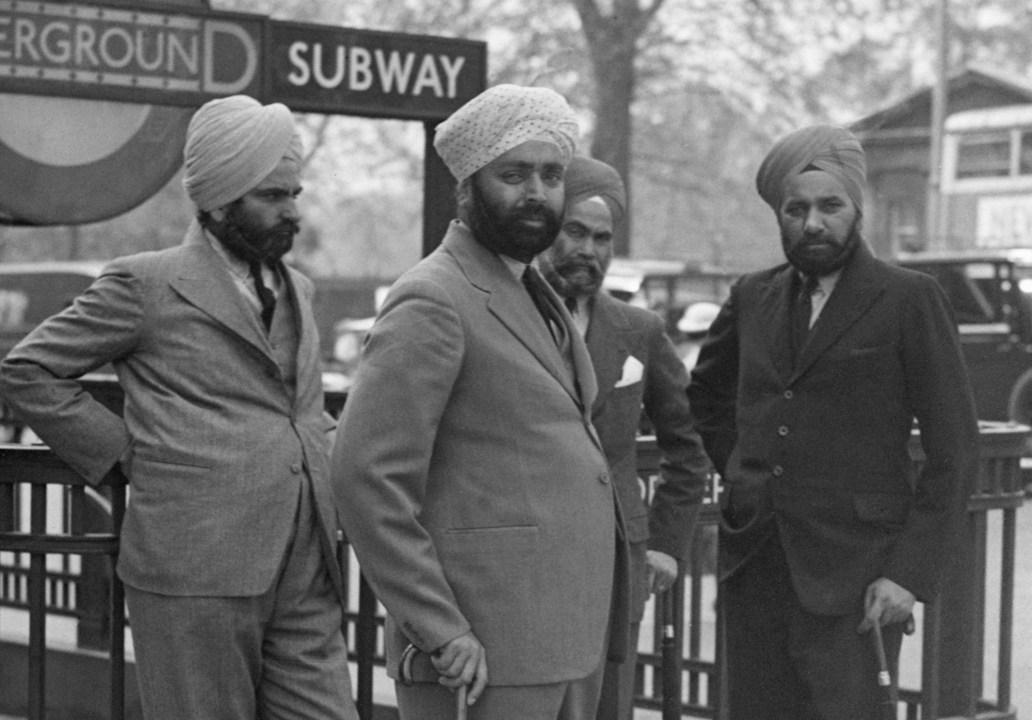

There were agonised debates in Britain whether to let in this suspect brown class. Sense prevailed. Edward Heath was the prime minister. It was perhaps his most courageous and positive decision. Enoch Powell was the leading voice against. He advocated strict immigration controls and opposed admitting non-white Commonwealth citizens, even those with British passports. It is a shameful blemish.

Amin had accused the Indians of economic dominance, disloyalty and sabotaging the economy. The Ugandan economy subsequently collapsed.

Britain was the subsequent winner. The Asians opened corner shops and voted for Thatcher. Their kids excelled in school and have built massive reputations in the professions and business.

Most Ugandan Indians were descendants of indentured labourers and merchants brought by the British in the 1890s to work on the Uganda Railway and to serve in commerce and administration. By the 1970s, they controlled significant portions of Uganda’s economy, contributing around 90 per cent of tax revenues despite being a small minority.

The expulsion targeted those with British, Indian, Pakistani, or Bangladeshi citizenship, though Amin briefly extended it to Ugandan citizens of Asian descent before rescinding that order. Around 28,000 Ugandan Asians, mostly British passport holders, migrated to the UK, with others settling in Canada (7,000), India (4,500), Kenya, Pakistan, and elsewhere. A tiny number of people whose contributions were massive.

Expellees were allowed only to leave with £50 and limited possessions, leaving behind businesses, homes, and assets. Approximately 5,655 firms, ranches, farms, and estates were confiscated and redistributed to Amin’s conies.

A significant portion of Ugandan Asians were Gujarati, primarily from the Indian state of Gujarat. This included Hindu, Muslim (notably Ismaili), and Sikh communities, with many tracing their roots to Gujarat’s entrepreneurial castes, such as the Patidar (Patel) and Lohana.

Gujaratis had a long history of trade and migration, initially moving to East Africa in the 19th century as ‘passenger Indians’ to pursue business opportunities under British colonial rule. Their commercial acumen made them dominant in Uganda’s retail, banking, and manufacturing sectors by the 1970s.

Their cultural emphasis on education, hard work, and community support carried over to Britain, aiding their rapid integration and success. They started by opening corner shops, working every hour God gave them, and their grandchildren have become consultants, lawyers, dentists and wealth creators. This has not been the story with other immigrant groups.

Neither are Indians inherently anti-Semitic, or inclined to advocate the replacement of law by religion. Indeed, they are sympathetic to Jews, with whom they share many values.

Ugandan Asians, particularly Gujaratis, transformed their displacement into opportunity, becoming one of Britain’s most successful immigrant groups, as noted by former Prime Minister David Cameron in 2012: ‘One of the most successful groups of immigrants anywhere in the history of the world.’ It is painful to admit but he was correct.

I don’t doubt for a moment the mendacity and desperation of Labour to offer India a lopsided trade deal. But the law of unintended consequences may finally redeem this government. Britain could benefit hugely from a dose of reverse colonisation by people who might make things better, not worse. Let’s just hope the best and brightest don’t leave after three years.

Comments