‘Moaning Minnies’ is how the Health Secretary Wes Streeting has described GPs opposing his rollout of online appointment booking. Originally, that moniker referred to German artillery pieces – and it’s pleasant for a doctor like myself to imagine we still possess that sort of firepower. But Streeting meant that the British Medical Association’s GP committee, which he has accused of undermining the attempt to make primary care more accessible, are a bunch of whining complainers, rather than us ordinary doctors. So, is Streeting right?

General practice, as everyone is painfully aware, is in trouble. Except in a shrinking minority of places, the old model that made it so valuable is dead. Continuity of care, a practice covering its own out-of-hours emergencies, even the basic ability to make an appointment and see a doctor, all of these are vanishing or vanished. This is a tragedy, because when patients and doctors know each other, general practice becomes effective and efficient, GPs are loved and trusted, and their working lives become satisfying – purposeful rather than defensive.

General practice was the jewel of the NHS

The current row between Streeting and the BMA is about making surgeries more responsive to online consultations, messages and bookings. The government agreed to a set of changes last February which started on 1 October. They haven’t gone well, certainly not as well as Streeting would like. He says he’s standing up for patient rights in the face of recalcitrant medics. The BMA’s General Practice Committee say they’re trying to keep patients safe.

Last month a survey said a third of GPs were willing to strike over the issue. Their argument is that in opening what is effectively an additional online shopfront, they’re unable to keep up with the extra work, consuming – according to the same survey – the equivalent of 200,000 appointments each week. Currently GPs are contractually obliged to keep their online door open between 8 a.m. and 6.30 p.m., but the BMA is formally in dispute with the government about doing so.

‘I think there’s probably a level of health literacy expectation in the policymakers that doesn’t exist for everybody on the ground,’ a GP in Norfolk said, giving the example of a patient of hers who used an online change-of-address form to say that they had been vomiting blood all weekend. Another GP cited a patient whose online message, at 6.25 p.m., said they were suicidal. Others pointed out that online forms provided a new avenue for timewasters – a group small in number but big in impact – with people consulting for trivia several times a day, and even from abroad.

To get our work done, we all rely on some freedom from interruptions. To answer an online query from a patient you know well might be quick, but today’s lack of continuity of care – and the need to allow GPs to concentrate on the patients physically in front of them – means many queries will be answered by doctors without that knowledge. Working out what’s urgent and what isn’t, what’s important and what’s trivial, takes more time if the patient is a stranger.

The sort of sweeping solutions that sound easy are often neither easy nor, when it comes to it, solutions. There might be a role for AI in triaging online contact, but at best it’s going to be helpful, not curative, and it could easily be done so badly as to make the situation worse. Nor would charging people for online contact be a panacea. Charges require safeguards so that catastrophe doesn’t become the penalty for penury, and many of those whose lives are poor of sense and organisation and civic duty are also impoverished financially. Charges won’t deter them, but may block others who shouldn’t hesitate – people who will put themselves at risk by pausing before a paywall.

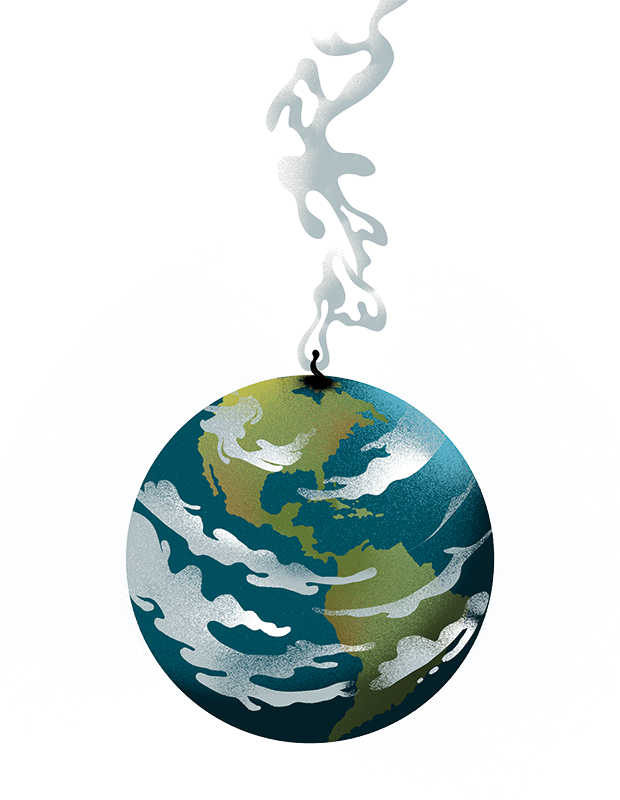

General practice was the jewel of the NHS, and continuity of care was what made it so. How to get that back, or how to structure primary care without it, is a genuinely difficult puzzle. Bringing GP surgeries online, and maximising the benefits without magnifying the dangers, is a challenge.

Both are worthwhile problems, and worth arguing over. Safety and quality do not always mesh easily with efficiency and open access. Elsewhere in medicine, when trying to work out different strategies for treating patients, we conduct randomised trials, looking for experimental evidence about what works best. We rarely do that when it comes to policy or to the way services are provided.

We should do it more. Not because trials are perfect, but because they force us to test assumptions and measure impact. The solutions would not be instant, and they might only help a little, but their successes would be cumulative, their flaws demonstrable, and the experiments would remind us that fundamentally, GPs and government and patients alike want to make things better. The NHS prefers to go no further than pilot projects, usually designed in such a way that nothing useful can really be learnt from them. Trials help show which objections are whines and which are vital. Better to recognise that disagreement can be constructive and that not all objections are moans.

Comments