History doesn’t repeat itself. But it does echo. The United States of the 1970s and Britain of the mid-2020s share more in common than we might first admit: economic drift, institutional distrust, foreign policy muddles, and a political class that’s treading water. The question now is whether the UK, like America in 1980, is approaching a political inflexion point, one that could shape the next decade.

In 1968, Richard Nixon won the presidency by forging a coalition of traditional Republicans and culturally conservative working-class voters, the so-called ‘silent majority’. He spoke to those unsettled by the cultural turbulence of the 1960s, offering a firm alternative. His presidency ended in scandal, but the political realignment he triggered proved enduring.

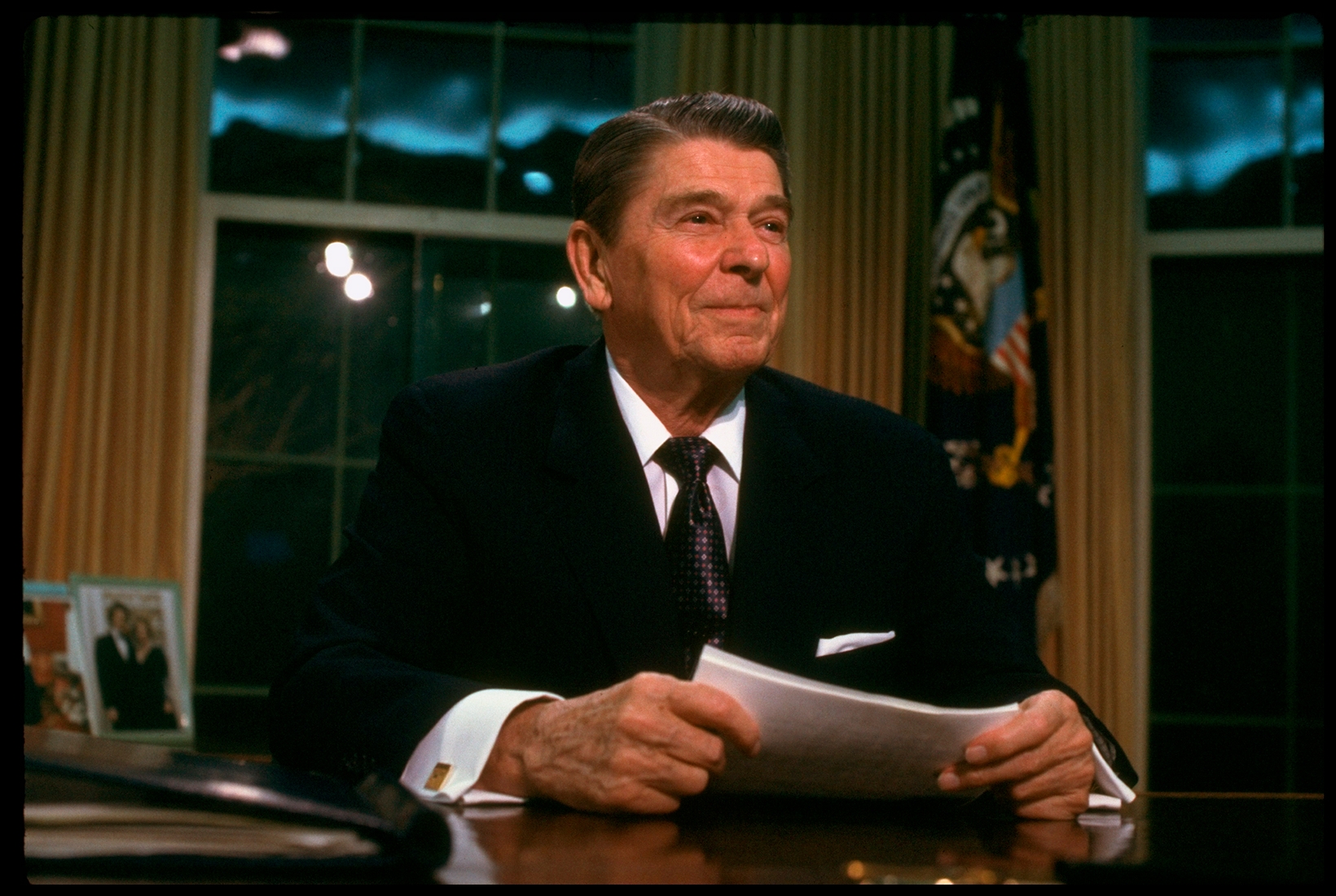

Reagan did something few politicians can achieve – he changed the national mood

In 2019, Boris Johnson pulled off a similar feat. He redrew the political map by uniting traditional Tory voters with disillusioned, often working-class, Labour Leavers. He promised to ‘get Brexit done’, but what he really offered was something broader, a break from technocratic stasis and a sense of restored national agency.

Like Nixon, Johnson was a deeply flawed operator. But where Nixon’s downfall stemmed from a calculated abuse of state power, Johnson’s stemmed from chaos and carelessness.

Still, Johnson’s rule fell under the weight of controversy of his own making (think ‘Partygate’ as a lower-grade version of ‘Watergate’). However, like Nixon, his success revealed something crucial: the old electoral alliances were dead, and a new coalition was emerging.

What came next in both countries, however, was not renewal, but drift. After Nixon, it was Gerald Ford. After Johnson, Rishi Sunak. Competent and moderate, both served as interims rather than leaders. They steadied the ship without ever defining its course.

Then came Jimmy Carter, a president chosen just as much for what he wasn’t as for what he was. On the surface, he seemed not to be corrupt and was deemed clean. He was moral, detail-oriented, but fundamentally managerial. Ultimately, he was overwhelmed.

Carter is best remembered for the Iranian hostage crisis, a foreign policy debacle that he couldn’t solve that seemed to symbolise American impotence. But it wasn’t just Iran. It was stagflation. Malaise. A sense that the world was changing, and the White House was simply reacting, rather than leading.

Sir Kier Starmer may be Britain’s Carter. The Labour Party was elected to restore competence and be careful – a safe pair of hands. However, a primary reason was that his party was not the Conservative Party. He inherited a country that, like late-70s America, is weary, frayed, and trying to find its place in the world. And like Carter, Starmer is already facing foreign policy pressure, particularly over Israel-Palestine, that threatens to fracture his coalition just a year into his government.

None of this is to diminish Carter or Starmer. Countries often require managers to tidy up after a period of ideological fatigue. But neither man offered a compelling vision for the nation’s future. They are meant to stabilise, but they do not motivate.

Which brings us to what came next in America: Ronald Reagan. Reagan did something few politicians can achieve – he changed the national mood. He offered more than policy. He offered purpose. He wrapped free-market economics in moral clarity and offered a renewed sense of national confidence. His presidency wasn’t flawless but it was an era of renewal. He re-established America’s ideological dominance on the world stage and left a legacy that shaped US politics for a generation.

Could the UK be approaching a similar opportunity? No one currently in British politics is quite ready to play the Reagan role. There is no apparent heir to a new economic conservatism, nor is there a singular figurehead capable of uniting the fragments of the post-Johnson right. But the conditions may be ripening.

The electorate is becoming increasingly exhausted. The turnout at the 2024 general election was 59.7 per cent, the lowest at a general election for more than 20 years. Only one in five of those on the electoral roll voted for the current government.

Labour may very well stumble under the weight of its own triangulations, trying to please both eco-activists and energy firms, Israel’s critics and NATO’s allies, as well as public sector unions and private sector reformers. Starmer has promised ‘change’, but the content remains vague.

Into that vacuum, someone could step in with a bolder platform. Offering a return to growth through market liberalism and a national identity based not on culture war panic, but on economic purpose. Britain needs to find a leader who promotes a return towards innovation, trade and entrepreneurial spirit.

It won’t be easy. Britain in 2025 is far from what America was in 1980. The UK isn’t on the verge of reasserting global dominance, and fiscal headroom is much tighter. Our state is bloated and protected by institutional inertia. However, even minor changes could push Britain off the path to perdition.

Just as Reagan inherited a tired America and turned it into a story of pride and prosperity, there is room soon for a British leader to do the same. If Johnson was our Nixon and Starmer is our Carter, then the question isn’t if, but when, a British Reagan emerges.

Comments